John Britten was a revolutionary motorcycle designer whose home-brewed machine won international plaudits with its stunning design and performance. The 300+ km/h blur of speed, the smell of burning rubber and the distinctive roar of the Britten V1000 motorcycle linger over the tarmac of kiwi myth and the world of motorcycle design. From his backyard in Christchurch John Britten melded the edges of design and engineering, the acclamation testifying to a visionary talent: “man against the manufacturers”, design genius, engineer, artist, thinker, entrepreneur, “the last of the great privateers”, inventor, “Renaissance man” – as well as architect, builder, glider pilot and glass sculptor.

In a poll compiled by the world’s leading motorcycle writers to rank the Motorcyclist of the Millennium, John Britten was placed equal with the four founders of Harley Davidson. Guggenheim curator Ultan Guilfoyle, places Britten, as “the New Zealander who stood the world of racing-motorcycle design on its head.” He says Britten was among his best three exemplars of bike design and he lauds the V1000 as “perhaps the most influential racing motorcycle of the Nineties.” Variously described as state-of-the-art, novel, avant-garde, revolutionary, exotic, innovative, unique, as much an “organic thing of beauty” as a race-winning machine – the V1000 stormed the international circuit. It broke world speed records, and leaving the factory-built Ducatis and Hondas behind the blurred brilliance of its sleek aerodynamics.

“It’s the world’s most advanced motorcycle, and it’s not from Japan, Germany, Italy or America.” proclaimed the cover of American motorcycle magazine Cycle World.

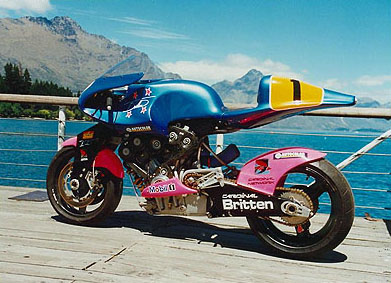

The Remarkables: The Britten at Queenstown Permission Estate of J K Britten

The John Britten story is firmly from the fringes, an affirmation of one man’s passion for an idea battling against convention, resources and manufacturing might. He threw away the rulebook and built the world’s fastest bike in his spare time. The V1000 bears its edge DNA on its carbon-fibre skin: the Southern Cross is tattooed into the bold metallic blue, and the B of Britten’s signature is said to have been designed to resemble a kiwi … The prototype engine was baked in a backyard kiln and the shell modelled with No. 8 fencing wire and a glue gun. Patrick Bodden, describing Britten’s designs as the “privateer’s last stand” in an age of generic factory-born superbikes, writes in The Interactive Motorcycle:

“It takes someone like John Britten to remind us that individual thought and passion can still challenge and on occasion, beat the very best teams of engineers and the orthodoxy in which they have embedded current motorcycle design. Evolution alone won’t sustain such an effort – nothing short of revolution will do! In designing and building the motorcycle that bears his name, John pushed his reference materials to the edges of his work area and began with a blank sheet, an open mind, and a fertile imagination. His stunningly beautiful and effective creation affirmed for the entire motorcycling community the intrinsic value of working to build a better bike and the potential of an individual to make it happen.”

“All Our Dreams Are Made Of Chrome” (Tom Waits)

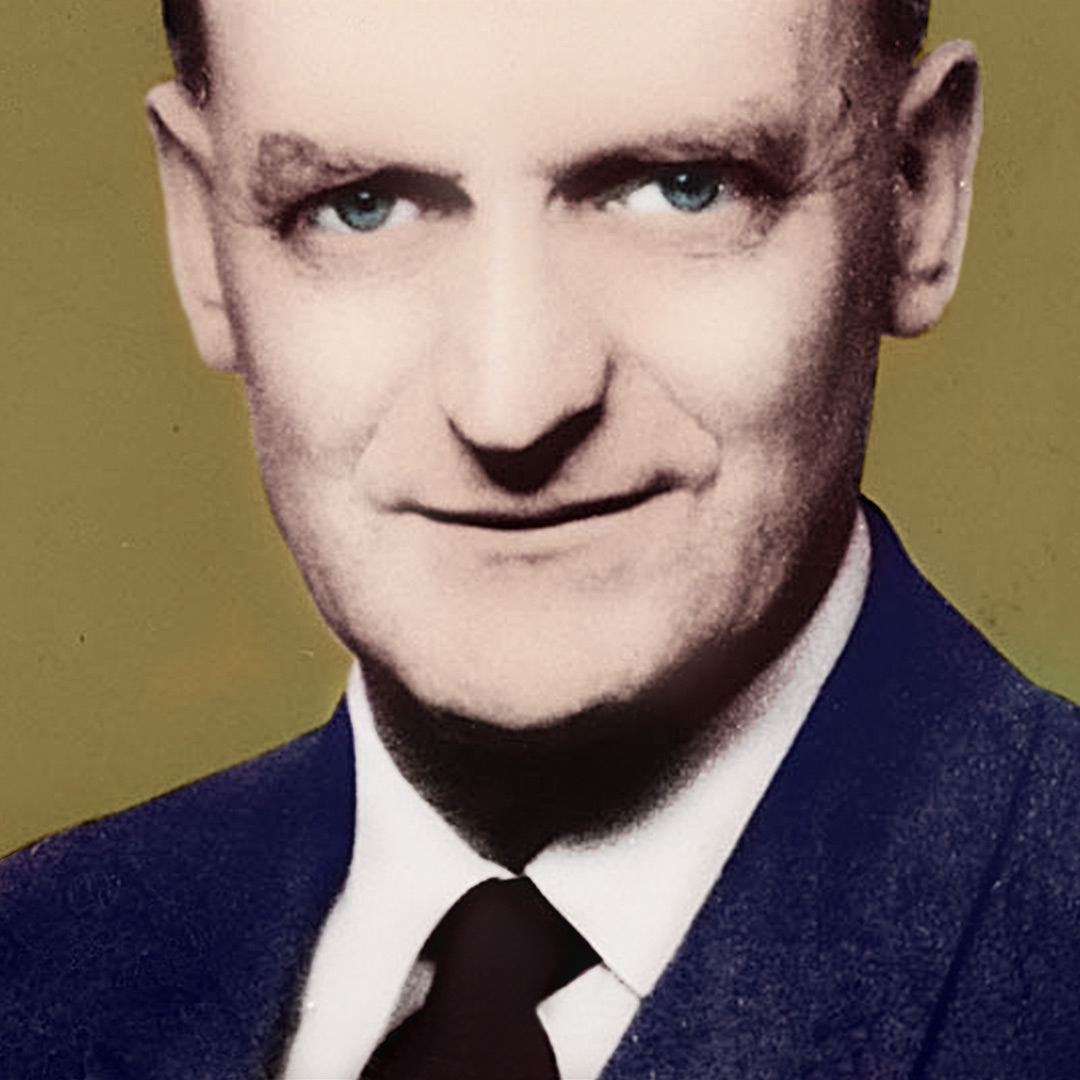

John Kenton Britten was born in Christchurch on 1 August 1950 to parents Bruce and Margaret Ruvae. He has a twin sister Marguerite and an older sister Dorenda, a prominent New Zealand industrial designer and design educator. As a child Britten built go-carts out of disused packing cases and at twelve had saved enough pocket money to buy a petrol motor and build a motor-powered version. Mucking around with old engines Britten and his mate Bruce Garrick stripped them apart, reassembled them, trying to figure out their internal mechanics: what made them tick. The streets of the Christchurch suburb of Fendalton became test tracks for new cart designs, propelled by small but high-powered internal combustion engines. At thirteen, on a visit to a farm in Gore, Britten and Garrick, budding archaeologists of the machine age, found a heap of red metal buried in an irrigation ditch and after freighting the carcass back to Christchurch by train, set about restoring a classic Indian Scout motorcycle.

After attending St Andrew’s College, Christchurch, Britten completed a four-year mechanical engineering course and was employed as a cadet draughtsman at ICI, working on mould design, pattern design, metal spinning and other engineering disciplines. He then took his OE, travelling to the United Kingdom to work for four months under Sir Alexander Gibbs and Partners on a highway design linking the M1 to the M4.

After touring through Europe he returned to New Zealand to take up a position as design engineer for Rowe Engineering, working on on-road equipment and heavy machinery. Two years later, in 1976, Britten redirected his creative energies, building his own kiln and establishing a career as a fine artist designing and crafting hand-made glass lighting. At 32, he married Kirsteen Price, an international model who in the eighties had worked with Cheryl Tieggs, Andie McDowell, David Bailey and Patrick Demarchelier, and whose face had graced the covers of Vogue and Marie Claire. Now with family commitments, Britten sold his glass lighting business and in 1987 joined the family property management and development company, Brittco Management Limited. The first project he conceived and developed was an up-market twelve story apartment building overlooking Christchurch’s Hagley Park. Named “Heatherlea” it was completed in 1990 and was a financial success.

While property development occupied his daylight hours, Britten used his nights to fulfil his instinct for construction and creation. He was conscious of avoiding the earlier constrictions he’d felt as an engineer working for a wage, designing things he wasn’t particularly interested in. “I still had an interest in engineering, but I wanted to choose the item of engineering myself. You’re more likely to succeed if you can choose what you want to design”.

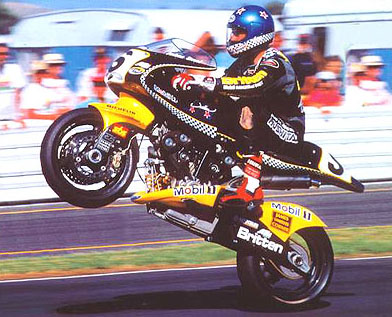

John Britten racing his Ducati Permission Estate of J K Britten

In his late twenties he had begun to race motorcycles in local Christchurch competitions, and in 1986, unhappy with the performance of the bikes he was riding, Britten decided to re-design his Ducati racing bike by creating his own body-work. When the motor and chassis proved unreliable he turned to a New Zealand made Denco motor in a home built frame. From here Britten became determined to design a prototype racing bike from scratch.

Self taught, Britten started with a blank canvas in what was then little more than a garden shed – the first incarnation of the Britten design, engineering and speed laboratory. Constrained only by his imagination, he drew on a lifetime’s experience of creating value from nothing. He combined modern technology with the resources around him. He drew on his innate ingenuity and foresight that served him well from childhood: from designing go-carts and restoring machinery rescued from rust, to his hand-crafted boardroom table and the 15 years spent converting derelict Victorian stables to an architecturally sophisticated family home, complete with Art Nouveau-inspired detailing.

Free from pressures to conform, Britten’s first drive was to exploit New Zealand’s geographical distance from the conforming orthodoxies of the centre. He was following in the footsteps of fellow visionary Richard Pearse who, almost a century earlier, conjured up one of the first flying machines from farm scraps in his shed down the road in Temuka.

As Britten stated in a 1993 interview:

“I guess I’m simply free of any constraints. I can take a fresh look at things, unlike a designer working for, say, the Jaguar company, who is obliged to continue the Jaguar look.”

Unlike the established manufacturers, who were obligated to match huge investment dollars, Britten could persevere on a trial-and-error basis until his vision was transformed to machine. Shaun Craill in a tribute to Britten in Pro-Design writes that Britten’s strength was that he could begin from first principles. “He didn’t understand he was being unconventional because he hadn’t been taught what conventional design was … The ability to see outside the box is a lot easier if you haven’t been shown the confines of the box in the first place. ‘Not possible’ was a foreign concept to Britten.” He and his team of many willing helpers conceived and built everything themselves, doing their own drawings, making their own patterns and designing their own engine.

Working through a point of design with engineer Ron Selby Photo: Simon Barker

By 1990 Britten’s privateer efforts were making racing history and in the Britten V1000’s international racing debut at the USA Battle of Twins in Daytona, Florida, it finished third. He followed this up a year later with a second at the same race. The efforts of an individual and a small team of enthusiasts competing against the manufacturing world’s trophy models had begun to attract worldwide attention, particularly from the countries which had come to dominate motorcycle racing and design: Japan, Italy and the US. Britten realised that he’d gone as far as he could with his original concept: a 2 cylinder, 1000cc with a liquid cooled 60 degree v-twin, fitted within a short wheel-base.

In 1992 he set about completely redesigning the bike. In the same year he set up Britten Motorcycle Company, which was initially located in the garage/workshop at his family home (later moving to its current premises in central Christchurch). He employed eight staff, mostly the same friends who helped him in his backyard and had survived to earn a salary. He attracted sponsorship from computer hardware company Cardinal Network after approaching Gil Simpson (chief executive and owner of Cardinal Network’s parent company Aoraki Corporation). Simpson was keen to support local ventures, and the bike was renamed the Cardinal Britten. The redesigned won its first race on the international circuit in the International Twins at Assen in the Netherlands. Then Britten took the new model back to the prestigious Daytona race. Hopes were high.

The Britten Team

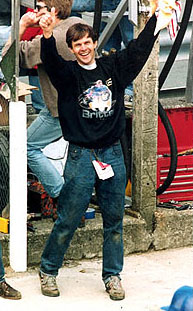

John Britten celebrating at Daytona. Permission Estate of J K Britte

“Yeah, Darlin’ Go Make It Happen” (Steppenwolf)

Ridden by Aucklander Andrew Stroud, the new V1000 dominated the 1992 Daytona Supertwins race. Right from the starting grid it exploded to the front. Footage of the Race shows Stroud toying with rival Ducati Ferracci rider Pascal Picotte. Time and again he grants the French rider space before almost insouciantly reeling him in, the super-machine cheekily pulling wheel-stands next to the unamused Picotte. In the second to last lap an electrical fault (a cross-wired battery) forced Stroud to pull out, frustratingly allowing Picotte to pass. Faulty part or not, the attention of racing aficionados was ignited: the Britten had arrived. American Cycle World proclaimed simply: “Stunner. Britten V1000” and the European Motociclismo devoted a ten-page spread to the bike. After the race, the designer of the bike that was almost entirely self-designed and built was heard to wryly remark: “[it] serves me right for using a Ducati part”.

After Daytona the Britten team returned to New Zealand to further refine the design and in 1993, at Raupuna, the Britten became the first New Zealand built bike to win the national Formula One title. In 1994 the team defended the New Zealand Grand Prix title and took the bike to Bathurst in New South Wales, Australia. It won the British, European, American (BEARS) race and finished second in the open events.

Victory at Bathurst Permission Britten Motorcycle Website – Unofficial

In 1994 the V1000 broke four FIM World Speed Records in the 1000cc and under category: the flying mile (302.705 km/h), the standing mile (134.617 km/h), the standing start mile (213.512 km/h), and the standing start kilometre (186.245 km/h), proving itself as the fastest thing on two wheels in its class.

The 1994 version of the V1000 was a brightly coloured pink and blue collage of technical marvel and innovation. The entry on the Britten bike in the book of the 1998 Guggenheim “Art and the Motorcycle” affectionately catalogues the technical specifications of the machine: “It has a bore of 99mm and is fed by two Bosch fuel injectors. A bell drives double overhead crankshafts with four valves per cylinder, producing 165 horsepower at 12400 rpm. Lubrication oil is held in a wet sump. The V1000’s careful construction, balancing and assembly resulted in an exceptionally smooth motor, so no counter balancers were included. Primary drive is controlled by gears, followed by a dry clutch and five speed transmission. Its frame is highly unconventional, structurally composed of carbon fibre and Kevlar composites. The innovative use of carbon fibre (a fabric more commonly used in the construction of yachts and ski-boots) meant the generation of extra speed on the race track due to its lightness and strength. A beam is bolted to the top of the cylinders and stretched out to hold the saddle. Attached to the front of the engine is a modernised version of girder forks, which sits upright, attached to a swinging arm by a long connecting rod, giving the bike an almost intuitive sense of the road. A unique piece of motorcycle architecture, Britten describes it as, “a girder parallelogram, semi intelligent front suspension, which is much more sophisticated than a conventional motorbike in that it can differentiate between a bike or a bump force.” The sleek form, from the shark nosed front fairing to the rapidly tapering tail fairing give the V1000 aerodynamics unparalleled by other motorcycles.”

The 1994 version of the V1000 was a brightly coloured pink and blue collage of technical marvel and innovation. The entry on the Britten bike in the book of the 1998 Guggenheim “Art and the Motorcycle” affectionately catalogues the technical specifications of the machine: “It has a bore of 99mm and is fed by two Bosch fuel injectors. A bell drives double overhead crankshafts with four valves per cylinder, producing 165 horsepower at 12400 rpm. Lubrication oil is held in a wet sump. The V1000’s careful construction, balancing and assembly resulted in an exceptionally smooth motor, so no counter balancers were included. Primary drive is controlled by gears, followed by a dry clutch and five speed transmission. Its frame is highly unconventional, structurally composed of carbon fibre and Kevlar composites. The innovative use of carbon fibre (a fabric more commonly used in the construction of yachts and ski-boots) meant the generation of extra speed on the race track due to its lightness and strength. A beam is bolted to the top of the cylinders and stretched out to hold the saddle. Attached to the front of the engine is a modernised version of girder forks, which sits upright, attached to a swinging arm by a long connecting rod, giving the bike an almost intuitive sense of the road. A unique piece of motorcycle architecture, Britten describes it as, “a girder parallelogram, semi intelligent front suspension, which is much more sophisticated than a conventional motorbike in that it can differentiate between a bike or a bump force.” The sleek form, from the shark nosed front fairing to the rapidly tapering tail fairing give the V1000 aerodynamics unparalleled by other motorcycles.”

The investment of time, energy and resource means that the bikes do not come cheap, as the entry on the V1000 in the Guggenheim exhibition catalogue concludes: “the price was high, US$100,000 plus, but the bikes were winners.”

The investment of time, energy and resource means that the bikes do not come cheap, as the entry on the V1000 in the Guggenheim exhibition catalogue concludes: “the price was high, US$100,000 plus, but the bikes were winners.”

“This Is My Hobby, Not My Living. I Am Totally Undercapitalised.”

Conscious of geographical distance from markets, cost and comparably minimal resources, Britten emphasised that his project was firmly niche. In an interview with New Zealand Sport Monthly in 1993 Britten stated “I don’t really expect it will rival the Japanese bikes for production numbers. It will probably always be a hand-built motorcycle. Quality is what I’m all about, not necessarily quantity …I have no aspirations to get into mass production as such.” From the patriotic paint job to his fidelity to his Christchurch base Britten recognised his New Zealand Edge, as he urged in an interview with NZ Business: “There is a niche market for Kiwis to exploit at the high quality, low volume end of manufacturing. It has to be top shelf.”

Faithful to his word and building on the international interest the racing bike’s successes aroused, Britten secured orders to build ten of his superbikes. Pulling a wheelie in the face of philosopher Walter Benjamin’s fear that mass mechanical production would mean that objects of art would lose their aura, the Britten bike gained allure from not just the rarity of its results but the individualism of its design. As the Chicago Tribune wrote:

“The Brittens, which sound just as distinctive as they look when roaring around a track, are revered by racers. Their mystique comes not only from their mind-blowing 185-m.p.h. top speed, but also from the fact that only 11 have been built by the eight-person motorcycle company that bears its founder’s name.”

Permission Britten Motorcycle Website – Unofficial

Modestly emphasising the craft of the art, Britten described himself as a “former racer who was never much good. A bit like a violinist who’s no maestro but makes his own Stradivarius”. The form of the V1000 was as startling as the pragmatics of its function: to win races. As Guggenheim curator Ultan Guilfoyle said: “All this engineering wizardry might have ended up looking like a techno-geek’s nightmare, but Britten’s genius was […] about turning his dream into an organic thing of beauty, as compact and powerful as a coiled spring …” A two-wheeled version of one of Len Lye’s kinetic sculptures, its distinctive pink and blue colourings suggest a futurist painting in motion.

“We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed.” Permission Britten Motorcycle Website – Unofficial

In 1995 the Britten bike, ridden by Andrew Stroud, stormed the international circuit, taking 1st place in the BEARS World Championship (an Italian owned Britten taking 2nd) and devastating the field at the Daytona World Twins, finishing 43 seconds ahead of the two Harley super-bikes and the latest model Bimota and Ducati V-twins. Earlier the Britten team had claimed the New Zealand Superbike Championship and the New Zealand Grand Prix as well as the New Zealand Battle of the Streets.

Legend And Legacy

At a time when Britten’s prodigious creativity had only just begun to make its mark, tragedy struck. Britten died, aged 45, on September 5, 1995 shortly after being diagnosed with melanomic cancer. He is survived by Kirsteen and three children, Sam, Isabelle and Jessica.

At Britten’s death tributes came from throughout New Zealand and around the world. Britain’s Independent lamented the loss of “the most original thinker in motorcycle engineering in recent years”. The Guggenheim catalogue entry wonders at what Britten might have gone on to achieve,

“These achievements within a few years were astounding; had he the opportunity for a full career, he might have gone on to produce more winning machines. The V1000 remains a legacy to Britten’s extraordinary talent as a motorcycle designer.”

All noted Britten’s generosity and intense optimism manifested through his love for motorbikes and the processes of their design. Shaun Craill writes in Pro-Design:

“Britten was an optimist. He believed in a better tomorrow and set about engineering it. It was impossible not to get caught up in his enthusiasm and vision – though there were plenty of times his team would have gladly traded this for a few extra hours sleep.”

With an apocalyptic roar that makes a Harley sound il castrato, the Britten was never destined for the suburbs. Grinning at the distinctive harsh, hollow, bark of the bike’s engine, Britten took an almost childish delight (from the streets of Fendalton to Daytona) in watching the bikes get put through their paces. “The bike takes a bit of getting used to. Not every one will adapt … the power can be a bit unsettling. I’m frightened by it. I give it a handful and ‘whoa’, I think to myself, and grab someone else to take over the test riding.” A modern Prometheus with just a hint of GE glee, Britten describes the feeling of animating technology, physics, art and metal into a super-bike as “… a bit like making something live”.

Since Britten’s death, the Britten Motorcycle Company has continued to win and bolster its reputation, for five consecutive years winning the Sound of Thunder at Daytona, as well as recording victories in Europe, Australia and at home in New Zealand. In its racing history the Britten has been placed in nearly every event that it has raced in. The ten bikes that Britten was commissioned to make have been completed and are variously being raced and displayed in public and private collections worldwide. The challenge and hope is that the Britten legacy will endure, just as the McLaren name has with the four-wheeled Formula One speedsters before him.

Motorcycle Mythology

“If the frontier symbol of the Nineteenth Century was one rider on his horse going west then in the Twentieth Century that rider is the man on his motorcycle …” asserts Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama, curator David Roos. Technology, mobility, freedom, rebellion, themes once personified by the car, which has now lost its romance as cars have become everyday and utilitarian objects, are still resonant in the mythology of the motorbike. From Marlon Brando in The Wild One, Fonda and Nicholson in Easy Rider, Cruise in Top Gun, through to the future vision of Schwarzennegger in Terminator, and Bruce Willis’ chopper in Pulp Fiction. In 1998 two major exhibitions opened detailing the expressive and pop-culture significance of the motorcycle, “The Art of the Motorcycle,” the attendance record breaking exhibition at New York’s Guggenheim Museum (the exhibition was designed by uber-architect Frank Gehry and has since travelled to the Guggenheim at Bilbao, Spain), and “Art on Wheels: Selections from the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum” at the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama. Both exhibitions carve a path to the Britten bike as a contemporary classic of motorcycle design. The icon on the show posters for “Art on Wheels” is the Britten V1000.

Darwinian design: poster for “The Art of the Motorcycle”

Great Britten

Along with the global recognition, world speed records and world championship titles, John Britten has been lauded by New Zealand motorcycling, design and engineering communities. He was the eighth person to be elected an Honorary Fellow of the Institute of Professional Engineers of New Zealand (IPENZ) in recognition of his outstanding contribution to the advancement of the science and profession of engineering.

Rich recognition for a person for whom a reading disability caused learning difficulties in his early education and who got his engineering qualifications through four years of night school. In February 1996 IPENZ posthumously awarded Britten an Entrepreneur Engineer Award for innovation, enterprise, entrepreneurial flair and services to the community. Memorial services were held by Biker’s Rights Organisations and motorcycle clubs throughout New Zealand to thank Britten for the work he did in promoting the profile of motorcycling.

John Britten was first brought to the attention of the wider New Zealand public with the screening of the 1994 documentary “Backyard Visionary”, tracing his achievements from his Christchurch garage to Daytona in 1993. This was followed in 1995 by the documentary “One Man’s Dream: The Britten Bike Story.” In 1995 an award was named in his honour by the New Zealand Design Institute to recognise excellence in design (America’s Cup designer Bruce Farr is the current recipient). This was recognition of the rare achievement for a designer, especially a New Zealand designer, in becoming a household hero. The Britten story has captured a nation’s imagination – the V1000 bike on display at Te Papa is one of the National Museum’s most popular exhibits.

John Britten with a model of the Cathedral Junction project Photo: Simon Barke

At the time of his death Britten was working on an innovative property development designed to run Christchurch’s historic tramway through a multi-million dollar shopping precinct named “Cathedral Junction.” His civic vision was that it would become a focal point of Christchurch, the building to be designed locally, artistically themed, and craft orientated in a design he called “Pacific Art Nouveau”. Under the shadow of the wings of Richard Pearse, Britten was also fascinated by flight. He studied the flying action of birds with the plan of building an “ornithopter” (a flying machine driven by wing action). He also conceived a lightweight commuter car made of wood and was developing a carbon-fibre pedal bike.

In the early decades of the 20th Century Richard Pearse, made his “power bike,” assembled from farm scraps. It was a time when when virtually anyone who wanted to build an engine, could make patterns for crankcases, cylinders, take them to local foundry, ram some sand, pour in molten metal and make a motor. The Britten V1000 is proof that one man, with one idea and a dedicated team, can still construct an exceptionally fine motorcycle on his own. Against the technical efficiencies and cash resource of the mass manufacturers (a factory revolution signaled in 1976 when Honda entered racing with the advertising slogan, “Honda Enters. Honda Wins”), Britten demonstrated that a design solution derived from an emotional response to a technical problem could succeed.

Permission Estate of J K Britten

“Designing bikes started for me as a hobby and in a funny way I just like to prove there’s room for the individual to compete against the multimillion dollar factory jobs. In practice you can’t because you’re continually undercapitalised, but essentially on a competitive basis, the Cardinal Britten has been recognised as the fastest four-stroke bike in the world.”

It is hard to resist the tempting pun “Great Britten” – but this evokes connotations of a country’s reliance on historical links, whereas the John Britten story is one wholly of the edge. A vision – “made everything but the tires” – that created revolutionary innovations, sparked the imagination of a nation, and beat the world’s best: a simple and single-minded devotion to an idea that turned a frame and two wheels into a design, racing and engineering legend.

Permission Estate of J K Britten

References

Web-links:

To visit the Britten legacy go to the Britten Motorcycle Company official website.

The unofficial Britten Motorcycle Website, created by Chris Goldie, includes an excellent archive of images, articles and sounds.

For a full account of the life and times of John Britten and the development and race history of the revolutionary motorcycles that bore his name see the biography of John Britten, by Tim Hanna http://www.timhanna.com.

Excellent article by Patrick Bodden in Interactive Motorcycle (“A compendium for the thinking rider”) placing Britten in the context of motorcycling innovation.

In design mag Metropolis Guggenheim curator Ultan Guilfoyle names his best bikes, a Stark Ducati, a Robb BMW, and … a Britten.

Tribute to Britten “the flying kiwi” in sportsbikeworld.co.uk.

The June 26-Sep 20, 1998, Guggenheim exhibition,”Art of the Motorcycle”.

With a laudatory mention of the Britten bike, a review of the Guggenheim exhibition after the exhibition’s journey to the Bilbao Guggenheim, Spain.

Review of the Guggenheim “Art of the Motorcycle” and Birmingham MOMA “Art on Wheels” exhibition in Antiques and the Arts online.

Britten and the restoration of the Indian Scout motorcycle.

Christchurch city COuncil page on the Cathedral Junction project.

Small note on the Britten bike in a Chicago Tribune article on the Barber Vintage Motorsports’ Museum.

Books:

Bridges, Jon and Downs, David (2000). No.8 Wire: The Best of Kiwi Ingenuity, Hodder Moa Beckett, Auckland.

Hanna, Tim (2003). John Britten, Craig Potton Publishing, Nelson.

Riley, Bob (1995). Kiwi Ingenuity: A Book of New Zealand Ideas and Inventions, AIT Press, Auckland.

Have just veiwed this record winning bike at motorcycle Mecca in Invercargill NZ where it is on display. Stunning.

Clearly the record figures are way up the wazoo here. The "standing mile" ir probably ¼ mile, and in mph not km/h, and the "standing kilometre" must be mph not km/h. Otherwise they're ridiculously slow.

I had the fortune of meeting genius John and his sensational bike at my office in Auckland in 1994. I also raced John at go-cart at a company event I invited him to speak at, he is a tough challenger, always creative in ways to lead. Love the man, love the bike, great loss to human kind. Aldo Grech.

This man & his bikes will dominate from now on,there is only the hiabossa that comes nearly close(or did John make those?)

I have only recently learned of this fantastic man, watching a film of his fanatacism to build a world beating motorcycle. Then to learn he had died of melanoma cancer...how trajic ..and such a grat man. One can only think what he might have achieved. How great but how sad.

hey this is really good :):):) thank yoou.. #PROUD #KIWI

john britten is cool

I am a kiwi living in France and just spent an enjoyable hour reading your site. It is fantastic. Thank you! I was visiting your site because I am about to deliver a presentation to a global audience and am telling them about me, as a kiwi. I wanted to show off about NZ and was thinking sports, as we do, but started looking for other ideas. How clever are we in NZ? From your site I get the feeling we must have the highest proportion of people who have been great contributors to the world per capital. Made me very proud and made me cry. I knew John Britten, he was such an amazing man, and your write up on him very much captures the spirit of the man and how he lived his life. Just great. I am telling the audience about another clever kiwi invention (it is not mine I just worked with it in NZ), so was looking for great things that have come out of NZ and I discovered your wonderful site. Kiwi France

The Britten is and still is to me the most amazing looking bike that I have ever seen and still is today. John was a legend in his own right and if he was still alive today, well, God only knows what the Britten motorbike would look like now. Forklift Driver New Zealand

I've had a look through and am impressed. Being a m/cycle fan I really enjoyed the Britten story. I will forward the site to lots of kiwis overseas I know. Customer Services Auckland, New Zealand

New Zealand for me was the land of John Britten (myself having been a motorcycle enthusiast since my teens) and The Piano. That was before I came here 10 years ago (I am an Indian-born "rubber-stamped" Kiwi). To me it is now a community of homely folk who really are modest and at the same time exceptionally gifted. Having travelled and lived in several parts of the world, I feel more strongly than ever that New Zealand must retain its essence - the Kiwi spirit. Consultant Wellington, New Zealand

I found your site because you'd used a couple of quotes from myself on the John Britten page. NZEDGE is an amazing project, I like it. My vote for someone to add to your hot list is Kiwi industrial designer Danny Coster, part of Apple's four person in house industrial design team responsible for the iMac (1998 and 2001), iBook, and G4. Danny has got to be one of NZ's most valuable Diaspora. Best regards, Shaun Craill Development Engineer Dunedin, New Zealand