How on (middle?) earth did one of the Twentieth Century’s most mythic and popular works of literature, JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, end up being translated into cinema in the largest movie project ever undertaken, by a team helmed by a maverick New Zealand director refusing to budge from his home-made studio at the edge of the planet … a director previously best known for his DIY Kiwi-schlock horror flicks and an art-house film about teenage matricide?

NZEDGE is proud to present a personal and fascinating account of the Peter Jackson story (thus far) by New Zealand filmmaker Costa Botes. Costa co-directed, wrote and produced with Peter the classic NZ mock-umentary Forgotten Silver in 1995. His account of Jackson’s journey is a steadfastly idiosyncratic case study of innovation, focus and energy from the edge; “In giving himself something to watch, Peter Jackson has given the rest of us good cause to shake off complacency and start thinking about how to realise a few other ‘impossible’ goals.” Roll on …

Made in New Zealand: The Cinema of Peter Jackson

By Costa Botes

It’s a bold statement, but I’ll make it anyway. There really is no branch of human endeavor more difficult to excel in than cinema.

It is the most technical of arts, and the most creatively demanding. It needs individual drive and excellence, yet depends on the skilful coordination of many hundreds of individuals. It requires a huge infrastructure and access to gigantic markets in order to contemplate the merest possibility of success.

Colin McKenzie (top) in Forgotten Silver

Once upon a time – in fact only a generation ago – the likelihood of anyone even making a feature film here in New Zealand was laughably remote. The prospect of a Kiwi film director creating a huge worldwide smash hit seemed utterly impossible.

In 1995, I wrote and directed a film with Peter Jackson called Forgotten Silver. For those who haven’t seen it, the story involves a fictional Kiwi filmmaker named Colin McKenzie.

Marooned in a time and place inimical to creative achievement (New Zealand, 1900-1931), McKenzie strives against awesome odds to realise the great cinematic masterpieces in his head.

The outcome of this life in film is either humorous or tragic, depending on your point of view. Despite being a peerless innovator and artist, McKenzie is alternately reviled and ignored during his lifetime. His legacy lies forgotten until a chance discovery brings it to light. Sixty years after his death, Colin McKenzie becomes an overnight success.

The twist in this tall tale was the presentation. It was delivered in the form of a documentary, complete with narration, interviews, stills and archival footage.

Although the illusion of fact was as perfect as humanly possible, we dropped in all kinds of obvious clues that the film was actually a parody, a ‘mock doc’, not to be taken at face value.

All the clues were ignored. The ‘hoax’ was swallowed hook, line, and sinker by a sizeable majority of that first night audience. This might suggest New Zealanders are a gullible lot, but I don’t think so. Rather, I think our audience wanted so much to believe this story was true, they chose to ignore all suggestions to the contrary.

Why? Because, if Forgotten Silver had been true, it would have satisfied the deepest secret need of every single New Zealander.

And what is that need? I guess it’s the desire of obscure colonials on the last inhabited edge of the planet, to be noticed; to meet and match their inspirations; to stake their place in the world. To believe that they’re the best.

On the morning I write this, Fellowship of the Ring has officially slipped into 6th place amongst the biggest grossing motion pictures in history, overtaking Star Wars. All this within a few short months of its cinema debut.

Peter Jackson has certainly been noticed, and in doing so, he has done more than most to stake New Zealand’s place in the world. This is no hoax. But it almost feels like one.

For some people, it’s just too great an achievement in too unlikely a form. Accordingly, I get asked the same question constantly. How has Jackson done this? What is his secret?

The inevitable flip-side of such questions is the assumption that understanding a person’s process can lead anyone else to the same result.

Sorry. Despite a self-help publishing industry to the contrary, life’s just not like that. Jackson’s story is unique to him, and likely to remain so. I offer these observations as one point of view on a complex, and extraordinarily gifted man; an extraordinarily lucky man, but someone, also, of whom it really is true to say he makes his own luck.

A DIY Guy

Peter Jackson is one of the smartest people I know, and the least pointy headed. He isn’t interested in the ‘whys’ and ‘wherefores’ of things terribly much. This article would probably bore him rigid.

Essentially, Peter was the kind of guy who latched on very early to the notion that he could make movies, so he just went out and ‘did’ it.

First with his Dad’s Super 8 camera. Then with a spring wound Bolex, shooting 16mm. Real movie film.

Peter’s need to make real movies was acute. In this, he was rare, but not unique (today, the supply of wannabes lining up for film schools is positively scary). The extraordinary thing about Peter was the capacity he demonstrated to act on his ambitions.

Planet of the Peters – Peter O’Herne in early PJ films. (photos: The Bastards Have Landed)

It isn’t the art in his childhood film making that’s striking, but the sheer hard work and ambition. The young Jackson was a self starter, a classic ‘Kiwi DIY’ proponent. He learned via trial and error and any instructional material he could lay his hands on: how to shoot and edit films, how to sculpt, and paint make-up prosthetics, construct miniature models, and execute a range of sophisticated special effects.

If Jackson had grown up in the world of his English born parents, his prodigious natural talent may well have been directed into more orthodox and neutral channels. Here in New Zealand, the young filmmaker had total freedom of thought and choice. He had no resources, no school, no contacts. But the quality of being free – to experiment, make mistakes, and mix up all one’s formative influences in a playground with no rules, no rigid history of how things ‘should’ be done was all the oxygen Jackson’s creative fires needed.

When I first met him in 1986, Peter was already a veteran. He’d been shooting his own movies since he was eight. These included numerous World War I epics, for which he continually dug up his parents lawn to recreate the Somme, Coldfinger, a Bond spoof, in which Jackson was eerily convincing as a Sean Connery lookalike, and Revenge of the Gravewalker, a wide screen zombie spectacular.

By now, he was deep into the third year of production on his most ambitious self-funded epic yet, Roast of the Day. This was the film that would eventually evolve into Jackson’s debut feature, Bad Taste. From start to finish, it was a triumph of dogged perseverance.

Stills from Bad Taste

No budget? Peter paid for it all himself out of his salary as a photo engraver. No equipment? Peter bought the minimum necessary – a camera with a sync speed motor, and built the rest himself, including his own dolly tracks, crane, and even a steadicam. No crew? No problem. Peter and stalwart friend, Ken Hammon, did it all. No cast? No worries. Colleagues from work volunteered, as a laugh, then stuck around for years of weekend filming.

Unfortunately, despite solid progress, the long gestating film took a body blow when a newly wed member of the core cast dropped out, forbidden to carry on shooting by his deeply religious bride. Peter’s indomitable spirit could move earth, but not heaven.

He’d also run out of cash. The day job as a photo engraver at The Evening Post just wasn’t up to financing a major motion picture.

By now, however, a few members of the film industry had got wind of this crazy maverick project, and they were impressed. NZ Film Commission CEO Jim Booth came to the rescue, drip feeding enough cash to stoke the flagging production back into life. Peter still had a hole where his story used to be, but he filled it with inspired sight gags and soldiered on.

Then fate dealt another lucky card. The ‘born again’ bride broke up with her husband, allowing Peter’s straying star to return to the fold. Bad Taste was back in business, and Jackson’s hobby finally exploded into a vocation.

From Pukerua Bay to Cannes

From Pukerua Bay to Cannes

Bad Taste was launched at Cannes, and became an instant cult classic. Jackson was hailed by horror fans as a new talent to watch. His trip to France was the first time he’d been out of New Zealand. When he showed me his travel snaps, they were full of pictures of McDonald’s. I asked why. Because, he said, that’s where he ate. He didn’t like foreign food.

I don’t recall what else the NZ Film Commission was selling at the market that year – but I do recall one anecdote relayed by a Commission staffer. She described a generally dour atmosphere at the NZFC stand, interrupted by gales of laughter coming from the side of the room where Peter was giving interviews.

This wasn’t the last time Peter would gatecrash a palace of high culture with his movies.

Bad Taste‘s New Zealand premiere was at the Wellington Film Festival. I was asked to write an introduction for their brochure by the Festival Director, Bill Gosden. He insisted I alter one line, where I compared Jackson to Buster Keaton.

Moo: Buster Keaton and a cow in the 1925 silent film, Go West

This, sniffed Bill, wouldn’t do at all. We eventually settled on a compromise. Jackson was likened to Laurel and Hardy instead. Sorry Bill, but this has bugged me ever since. I still think Keaton was the appropriate choice.

Baa. Go a little further west … Peter Jackson shoots a sheep; exploding icons in Bad Taste.

I’ll never forget that screening. The audience was tense and expectant. They’d come in on the promise of bizarre fun. Kiwi genre movies weren’t exactly thick on the ground, and there’d never been a good one.

They saw a great one that night. The ceiling of Wellington’s grand old lady, the Embassy, almost lifted off.

‘Derek’, Peter Jackson belts up in Bad Taste

Even after all this, the Peter Jackson story might have ended there – with Peter the latest in a long line of genre directors to deliver an auspicious debut, only to sink back into obscurity.

And now, here he was, with a feature film behind him. Precocious, perverse, with a wicked sense of humour and peerless talent for staging spectacle, Jackson found himself between two extremes – the cool indifference of the New Zealand Film Commission, and Hollywood offers he didn’t want to take.

Despite his popularity in the world of cult film (he was nicknamed the ‘Sultan of Splatter’ by fans), within New Zealand Jackson’s notoriety and preferred choice of genre didn’t exactly endear him to the local film establishment. It wouldn’t be too inaccurate to say they were embarrassed by him. The brain eating, green vomit exploding, eyeball popping of Bad Taste just didn’t fit the preferred profile for ‘New Zealand Cinema’.

I quietly hoped that Jackson would go the way of David Cronenberg (Rabid, Shivers), or George Miller (Mad Max), both of who started as reviled genre directors in their respective countries before securing viable international careers.

Although it was obvious Jackson wasn’t going to just give up and disappear, he didn’t seem to have too many options up his sleeve.

However, in plotting his follow-up to Bad Taste, Peter was to exhibit great strength of character. The choices he made seemed unwise and cocky at the time, but in hindsight one can see how they allowed him to grow as an artist, and thus helped lay the foundation for what followed.

Producer Jim Booth; photo from The Evening Post.

Between Movies

Most artists have to hack through a tangled thicket of negativity, logic, and procrastination on the way to creating anything.

Peter seems to be supernaturally free of any such concerns. This is a guy with a big wide conduit running from the creative, imaginative part of his brain, straight to the place where most of us keep our willpower.

That could be a recipe for a monstrously selfish ego. Again, Jackson’s ability to chase goals doesn’t come with that kind of baggage. He’s driven, and he’s incredibly demanding, but he’s always focused on results, never on himself.

In short, there’s a lovely, positive energy about this man that’s good to be around. It’s inspiring. And empowering. This attracts talented people. The sort of people Jackson would need as he went on to negotiate the most difficult phase of his career.

Jim Booth moved from the Film Commission to producing Peter’s subsequent pictures. Sadly for all of us to whom Jim was a mentor and friend, he passed away shortly after the completion of Heavenly Creatures in 1993, otherwise his partnership with Peter would certainly have endured.

Editor, Jamie Selkirk continues to be an important collaborator and business partner.

Fran Walsh and Peter at their investiture as, respectively, a Member and Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit, March 2002.

The most important creative liaison in Peter’s career, though, has been Fran Walsh. She and her then partner, playwright Stephen Sinclair, met Jackson while he was struggling to finish Bad Taste. Excited by the developing movie, Walsh and Sinclair immediately volunteered to help him write his next project.

Thus it was that Brain Dead got started. But it would be a few more years before that was to escape into the world.

First came Meet The Feebles.

Puppets Amok

After Bad Taste, Peter was able to secure a Hollywood lawyer/manager, and an agent. The offers started flowing in from L.A. Anyone else with no job and no immediate prospects would have jumped and never looked back (this ‘brain drain’ is a principal reason why after a quarter century of continuous feature film production, our cinema industry remains shaky and immature).

Common sense seemed to suggest that if he wanted to be a film director, Peter should move to where the work was. But he wasn’t interested in being a ‘film director’. He was interested in doing his own thing. And he judged correctly that this would be no more difficult here than anywhere else, so why move somewhere else when he was happier here?

Common sense seemed to suggest that if he wanted to be a film director, Peter should move to where the work was. But he wasn’t interested in being a ‘film director’. He was interested in doing his own thing. And he judged correctly that this would be no more difficult here than anywhere else, so why move somewhere else when he was happier here?

The fact that Peter skipped this particular dilemma with so little angst demonstrated how different he was to the common run of Kiwi filmmakers.

It’s kind of obvious, really. It comes back to self-expression. The place you live is a big part of that. For a filmmaker, the thing you make, the thing you want to sell, has to be unique, it has to be special. In a crowded marketplace filled with generic pictures, the elements that always stand out are story and style. The personality of the filmmaker is vital in determining both.

Whether or not he consciously thought it through in those terms, I have no idea, but somewhere in Peter’s mind, he must have made the connection between his own inspiration, his ability to see things differently from everyone else, and the place, the culture he grew up in.

In all likelihood, the reasoning was entirely selfish. As much as Peter loves to stretch the envelope, even burst through it in his professional life, on a more personal level, he likes the stability and comfort of the familiar. This was the guy, remember, who ate at McDonald’s in Paris.

Paradoxically, it’s that immersion in the cosy familiarity of ‘home’ which has allowed him to develop a point of view that’s fresh and unconventional.

What he did want to do, was make a puppet film. A twisted black comedy. A dark collision between The Muppets and Taxi Driver. It was to be a half hour short film. Cameron Chittock designed and built the puppets. A young Richard Taylor joined the crew designing models and special effects. George Port – who would go on to be a founding partner of Weta – was on the puppeteering team. Muppets go on vacation down under-world.

Meet The Feebles became a crucible into which Jackson poured in all the precocity, all the perversity he could muster. It was disgusting, vile, gross. And very funny.

After a year, it was also unfinished. Like Peter’s career, the film was teetering on the edge.

Then Peter had the bright idea of taking a rough cut to Cannes. A Japanese distributor saw it, and offered $250,000 – on condition that the short film was expanded into a feature, and finished in time for next year’s market.

It wasn’t enough money. He needed at least twice that much. And the deadline was crazy. But Peter went for it anyway.

The writing team was Peter, Fran Walsh, Stephen Sinclair, and Danny Mulheron. A lot of comedy firepower was sitting in that room. Some of the material they came up with was brilliant. Some of it was scatological nonsense. The structure of the story was hit and miss. But none of that mattered. The script had attitude, and cut deep into the funny bone.

Jim Booth came aboard as producer. His insider knowledge of film funding politics helped smooth the way to gaining the balance of the budget from the New Zealand Film Commission. However, they always remained, to say the least, uncomfortable with the project.

The film’s content alienated more than one member of the Commission Board. Peter had stuck his neck out and refused to compromise any of the script’s more far out excesses. Thus, when the shoot ran over time and budget, there was no comfort to be had from that quarter. I ran into Jim Booth at a fast food joint one night about this time. He was demoralised and angry, but Jim being Jim, he wasn’t dwelling on it. The plan seemed to be, grin and bear it.

In the event, the crew backed their director and finished the shoot with no pay.

There was to be no happy ending, no massive hit at the end of this rainbow. Peter’s insistence on retaining Meet The Feebles grosser sequences ensured the film failed to get wide distribution. On the other hand, its cult following remains strong to this day, when other, more ‘respectable’ films of the time have long been forgotten.

Peter later explained that he was most nervous about the reaction of his Japanese investors to the wicked Asian stereotypes in the film’s ‘Deer Hunter‘ parody (Winyard the Frog and his army buddies are taken prisoner in ‘Nam by Vietcong Mongeese, who proceed to eat their legs). The screening went well, and everyone seemed happy, so Peter asked the investors what their favorite sequence was. To a man, the Japanese reached up, pulled their eyes into slits, and made chattering noises like the Mongeese!

Brain Dead

Brain Dead

In the wake of Meet The Feebles, Peter still had a problem staying in New Zealand. His cult reputation was cemented, but local support remained grudging and relations with funding bureaucrats were frosty. Conversely, offers were flying from Hollywood, yet Peter was determined to ignore them.

One Hollywood expert, however, was to make a seismic impact on his future work.

In 1990, story analyst Robert McKee was brought to New Zealand by the Film Commission and delivered his famous seminar on screenplay story structure to packed lecture rooms in Auckland and Wellington. In the audience were Jackson and Fran Walsh.

Taking Notes: Robert McKee (L)

Over three days, McKee laid out a series of broad principles and practical tools which fell on the director and writer like thunderbolts. If any single event marks Jackson’s transition from flash in the pan local hero to internationally capable competitor, the McKee seminar is it.

Just a couple of years earlier, I recall Peter asking me to take a look at some pages of hand written notes he’d drawn up in planning the last phase of Bad Taste shooting. They were a joke. An almost incomprehensible jumble of notions that barely resembled a laundry list, let alone a screenplay.

In those days, Peter was finding his movies as he went along, virtually creating them on the spot. Meet The Feebles was a token advance. The script was ingenious and quirky, but also sketchy and disjointed.

Afterwards, in his heart of hearts, he must have known it wasn’t good enough. From then on, his grasp of screenwriting had to equal his mastery of the camera.

Lawnmower man Lionel (Tim Balme) comes to grips with his tools

Jackson and Walsh went back to their stalled zombie project, Brain Dead, and redesigned it from top to bottom. Through nine drafts, the script evolved from being a clever but wildly uneven series of gross sight gags, to an equally clever, but ultimately much more engaging story with powerfully interlocking elements.

Love, lawnmowers, body parts, gallons and gallons of blood. Brain Dead must rank as one of the grisliest, most shockingly violent pictures ever made; and also one of the funniest.

In hindsight, an amusing and telling aspect of the film’s production was the casting of the Spanish love interest, Paquita. Originally, one of the film’s key investors was to be a Spanish distributor. Their money was conditional on casting a Spanish actor in a leading role. The solution was to change the story’s love interest, a Kiwi shop girl, into the daughter of Spanish immigrants.

Peter thus found himself stuck with the onerous duty of auditioning a bevy of gorgeous Spanish girls. He found his ideal Paquita, and promised her the part.

And then, the Spanish investor dropped out. The money was found elsewhere, but Peter kept his promise. The Spanish girl stayed in the movie. Nobody ever questioned the veracity of the casting. Fran and Peter wove Paquita’s Spanish identity into the story so cleverly, it became an asset rather than an imposition.

Paquita and Lionel find 1950s suburbia a place as savage as the surname of the former NZ Prime Minster; where gardening implements are put to disturbing use.

In other respects, Peter paid much more attention to Brain Dead‘s Kiwi identity than he needed to. I don’t think anyone has ever quite captured the look and feel of 1950s Wellington on film as he has. There were not only the fantastic miniature buildings and model vehicles built by Richard Taylor’s effects workshop, but also a careful and affectionate recreation of language and customs of the period.

Essentially, Jackson delivered a popular genre film with universal appeal, which nevertheless evoked a clear sense of national identity.

The NZFC had long preached this as an ideal, but somehow or other, our films rarely delivered. And they still don’t, as if somehow these two things are naturally incompatible. It just takes a great deal of courage and talent to follow through on the rhetoric, and unfortunately, one or other is usually lacking.

At this point, if Jackson had been working in any other genre but horror, he would have been already certified a national treasure. Even his staunchest critics in the business had to take a step back at the sheer artfulness of this film. It was staggering, beyond belief, and it reeked ‘New Zealandness’ from every frame.

Dead calm: Sam Neill as he authoritatively appears in Forgotten Silver

A few years later, when Sam Neill made Cinema of Unease, a personal view of New Zealand film, Brain Dead figured large in his choice of favorites, as did Jackson’s next film.

Heavenly Creatures

If Brain Dead had some claims to historical veracity, this was nothing compared to the follow-up.

If Brain Dead had some claims to historical veracity, this was nothing compared to the follow-up.

Various filmmakers had tried and failed to tell the story of the Parker-Hulme murder case over the years. Many sensational ingredients for a good film story were there, but the raw facts seemed incomplete, impervious to a conventional cinematic treatment.

Nevertheless, at the time Peter began shooting Heavenly Creatures, there were reportedly up to six different scripts in development, including one that had been funded to a relatively advanced stage by the NZFC, and another being produced by Dustin Hoffmann.

None of those ever got off the ground. None of them, I suspect, even came close to doing the amount of preparatory research that fueled Jackson’s script. With relentless diligence, he did a detective job almost as remarkable as the finished film, fitting together all the missing pieces of the puzzle until the true shape of a compelling, and hugely dramatic tragedy was revealed.

Pauline (Melanie Lynskey) and Juliet (Kate Winslet) in Heavenly Creatures

I hope that one day Peter takes the time to share the details of his investigation. It’s not easy dredging up the past when many – not least the keepers of official records, and the protagonists themselves – wished to keep a lid on their secrets.

One example of Jackson’s dedication can be recounted here. It serves as a perfect metaphor for his efforts. He had already found black and white photographs of the Hulme family’s Port Levy summer house, but had no idea what colour it was painted in the 1950s. Anyone else would have built a recreation and settled for a best guess.

Jackson flew to Christchurch, drove two hours to the site, and then proceeded to dig in a grown over rubbish pile he found in the back. He emerged with a wooden shingle. Comparing it to his photographs, he realised he was holding a name plate that used to be screwed above the front door at the time of the Hulmes occupancy. Traces of original green paint still clung to the plate.

Thus, the colour the Port Levy house ended up being painted in the film was … exactly the right colour.

Peter’s vision of the story capitalised on all the elements which made the case so shocking, but he went much deeper than that. He demonstrated remarkable empathy with all the characters, not just the girls, and took infinite pains to tell their story as truly as possible.

Juliet (Kate Winslet) and Pauline (Melanie Lynskey) in Heavenly Creatures

The result was a wonderful piece of cinema, emotionally engaging, ultimately rather shattering, but also rather uplifting in the way that all great art can be. It was his first masterpiece, and it’s arguably still the best film ever made here.

The Birth of WETA

In order to create the sophisticated special effects, and expensive period recreations needed for Heavenly Creatures, Peter and a few key collaborators established WETA, or Wingnut Effects and Technical Allusions. Peter later explained that spelling was not his strong suit, and anyway, WETI didn’t sound quite right.

The partners in this new effects facility included Richard Taylor, whose workshop was going from strength to strength in the fields of makeup and miniatures, and George Port, an animator/puppeteer turned computer boffin. George set up a rudimentary CGI facility from scratch, got all the hardware and software working, and then nutted through all the effects needed for Heavenly Creatures.

(L) Pauline (Melanie Lynskey) meets an inhabitant of Borovnia, the medieval fantasy kingdom imagined by Parker and Hulme and realised by Jackson’s SFX team.

It was especially humorous watching poor George labouring to convert Orson Welles from colour to black and white over about 1,400 frames. All of which had to be done individually, by hand.

How we all laughed at this shonky enterprise, nicknaming it ‘ILM South’. In stark contrast to George Lucas’ multi million dollar FX behemoth, Industrial Light and Magic, Peter’s version was the ultimate in Kiwi DIY, the whole thing held together with prayers and number 8 fencing wire.

But the point was, it was there, and it worked.

Forgotten Silver & The Frighteners

Forgotten Silver & The Frighteners

If Peter hadn’t invested in the creation of WETA, if he’d just gone shopping for the effects he needed at a facility in the USA, then his film wouldn’t have got made at all. It would have been too expensive.

That was also the case for Forgotten Silver.

The idea for this movie had been around for several years, but we simply couldn’t afford to make it. Amongst all the logistical problems, the story needed vast ruined temples, and the recreation of a spectacular biblical epic. These things were impossible, until CGI, or computer generated imagery came along.

In the wake of Heavenly Creatures, not only did we have sophisticated special effects technology available, overnight Peter had become a poster boy for New Zealand Film. Finally, he was respectable!

I suggested that maybe the time was ripe to have a go at bringing our private little joke, the ‘mock doc’ to the screen. He agreed, and Forgotten Silver came out for a polish.

Laughing all the way to the Oscars (Wilde that is) – poster Boy PJ keeps his head on the set of Salome. (Photo by Chris Coad)

Leaving aside his efforts as a director (more on that below), it was as a producer and co-writer that Peter made his biggest contribution to this picture. As a producer, he was able to exert enough influence that we were left pretty much alone by our investors – an uncomfortable triumvirate of NZFC, NZ On Air (a public broadcasting fund), and Television New Zealand.

As a writer, Peter showed me how far he’d pulled ahead since the days when he scrawled rough ideas on pages of A4 refill. Most of the original story ideas in Forgotten Silver are mine, but I can honestly say there isn’t a single moment in the film that wasn’t reworked, overhauled, or somehow radically influenced by Jackson.

He was most brilliant in terms of articulating the spine of the story. It was Peter who came up with the key idea that held the whole thing together – the lost city of Colin McKenzie. The day this notion popped out, I finally saw the whole film unroll in front of me. This was definitely going to happen.

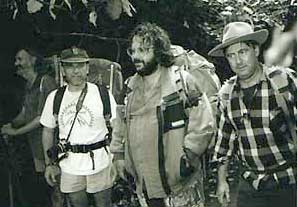

Going bush: the author (on the left) with Peter Jackson in search of Colin McKenzie’s fabled lost city. (Photo by Chris Co

And that is really the greatest gift one can get from any collaborator – communicating the sense that one can do it, along with a focus on how.

Peter is VERY good on both.

From then on, Peter’s mantra was consistent. Make it dramatic, make it real, make it emotionally engaging. It was an object lesson in something so obvious, we tend to overlook it all the time. No matter how good your gags are. No matter how great the special effects. No matter how much else you pull off, if the audience doesn’t care about the characters and story, the film’s dead in the water.

It has been said that the pain suffered by the writer is inversely proportional to the pleasure enjoyed by the audience. Writing Forgotten Silver was pure torture at times. I had the most demanding audience possible in Peter. He worked like sandpaper over my pages, exposing every cliché, every easy fix, or contrived transition. On the other hand, it was easy too. With a hurricane force talent like that in the same room, it was just a matter of getting the wind behind you!

In the event, an accident of timing conspired to make the funding for Forgotten Silver available just as Peter’s first Hollywood production, The Frighteners was going into pre-production.

This was not necessarily a good thing! The window on Peter’s availability was closing fast as we rushed to prepare his leg of the Forgotten Silver shoot – which largely involved recreating all of Colin McKenzie’s films.

Then, halfway through filming, a bombshell. Universal Studios executives were en-route to New Zealand, eager to start preparing for The Frighteners earlier than planned.

Peter had a problem. He couldn’t be in two places at once, and shooting couldn’t be postponed. Thus it was that the Universal men found themselves being escorted around exotic places of great interest around the Wellington area, while Peter was ‘taken ill’. There was also an ’emergency gas leak’ around Camperdown Studios which meant the whole facility had to be ‘evacuated’ for three days (actually, we were there filming).

In a sense, Forgotten Silver was a last chance for Peter to indulge in the kind of guerilla style, improvisatory mode of filmmaking he loved. It was just like doing Bad Taste, only now he had a crew, decent equipment, and his Mom didn’t have to do the catering.

“Roll action”. (Photo by Chris Coad)

Ideas for sequences were loosely sketched out. We’d talked about what was needed, the style and history of each piece of film, but within those parameters Peter was free to do pretty much whatever he wanted. What one sees here is not just a great deal of cinema scholarship – he absolutely nailed the characteristic style of each period – but a downright amazing ability to pull together large groups of people, and very quickly organise them into units of cinematic action.

The film’s battle sequences, especially the Gallipoli recreation, were marvelously authentic, and yet none of them took more than a few hours to shoot.

I think it was in trying to make the transition from this kind of organic, fun style of production, to the ultimately pre-planned, storyboarded, and tightly pre-constructed requirements of a big special effects driven flick that Jackson lost the plot on The Frighteners.

I think it was in trying to make the transition from this kind of organic, fun style of production, to the ultimately pre-planned, storyboarded, and tightly pre-constructed requirements of a big special effects driven flick that Jackson lost the plot on The Frighteners.

Maybe it was just the pace of post-production, which had to be accelerated to meet a hastily rearranged release date, or it could have been that the casting was wrong – with a miserable, haunted looking Michael J Fox stepping too far from type; perhaps the marketing promised a far merrier, simpler movie than the complex and very edgy picture Jackson ultimately delivered. Probably, it was a combination of all these and other factors which led The Frighteners to a relatively disappointing box office result. Artistically, it’s an interesting film that improves on repeat viewings, but it’s most definitely not a great one.

Weta creepy crawlies: Michael J. Fox and CGI apparitions in The Frighteners

On the positive side, Peter showed that his mastery of special effects and ability to choreograph spectacular action had gone from strength to strength. With backing from a large Hollywood studio, he was able to invest in the growth of Weta. Richard Taylor’s physical workshop, and the Digital FX side of the business grew exponentially. Fresh talent arrived from around the world, and a bunch of young New Zealand artists got an introduction to the industry.

Some of them, like Andrew Adamson, co-director of Shrek, went on to Hollywood. Many of them stayed here, and are now working on Lord of the Rings.

From Kong to Tolkein

If Peter Jackson has a single favourite movie, then it must be King Kong. When Universal announced they were backing a remake with Peter directing, I immediately thought two things:

If Peter Jackson has a single favourite movie, then it must be King Kong. When Universal announced they were backing a remake with Peter directing, I immediately thought two things:

Firstly, there was no better choice of director, and secondly, no matter what amazing things Peter did with the material, and I’m sure he would have, this was always going to be a ‘no-win’ project. It’s hard to compete with a classic. Jackson’s version would always exist in the light, if not the shadow of the original.

Universal eventually pulled the plug early in 1996, fearing a quagmire after another studio announced their own giant ape movie (it was the less than awe-inspiring remake of Mighty Joe Young). This was awful for Peter and Richard Taylor’s workshop, which had worked so hard on preparing for Kong, but my conviction that something better lay around the corner was soon confirmed.

A few weeks later, I got a very intriguing phone call from Fran Walsh. She and Peter were flying to Los Angeles to pitch a number of projects. They had designs on acquiring the rights to a rather famous book. They needed someone to prepare an accurate plot summary of this book so they could quickly move on to developing a filmic adaptation. When she told me what the book was, I immediately thought two things. First, that they were crazy … and second, that there was no other director on earth who could do it justice.

Strange lands, strange creatures: (L -R) Moa, King Kong, and the Lord of the Ring

Why? Because I knew him. Because of everything that’s set down here about his attitude and talent and taste. Peter Jackson is uniquely suited to translating JRR Tolkein into film.

Of course, the book was Lord of the Rings. I then spent the next ten days reading all three parts, summarising Tolkein’s plot as faithfully as I could, producing a kind of ‘cheater’s guide’, with page references. This was a simple exercise.

Pondering the task ahead for Fran and Peter, who had to somehow distil all this material into three compelling and cinematic screenplays, I vacillated between the same two extremes – from a conviction they really were nuts, to the inexplicable gut feeling they might actually pull it off.

Well, we often talk about the ‘Big One’ in the film industry, as in, “see you on the Big One”, the mythical film that never comes. They’re always too small, too hurried, too under-budgeted.

Now I can say that in my lifetime I’ve seen the Big One. And it really was a beautiful thing.

Director of Photography Andrew Lesnie half jokingly called Lord of the Rings, “the biggest low budget movie in the history of the planet”. Even with all the hundreds of millions spent on it, the film’s production has been characterised by a rough and ready, DIY feel. Even with the best, and brightest movie minds on the planet on the case, chaos and confusion have reigned. But somehow, the bright vision at the center of it all has shone undimmed.

It’s hard to comprehend the amount of detail Peter Jackson holds in his brain, sifting, collating, making a multitude of choices daily, all to keep this movie – actually three movies – on track, moving forward, being the best they can be. He’s had six years of Rings so far, with another two to go. It must take a toll – and yet, there he is, the classic Kiwi hero. Rumpled, unflappable, cheerfully barefoot in more ways than one.

Seeing loud: edge visionary Peter Jackson. (Photo by Chris Coad)

The Secret to Jackson’s Success

So what’s his secret? I said I couldn’t tell, but actually I can. Because it’s no secret. Peter talks about it all the time, but nobody seems to be listening. He makes movies for himself. Or, more correctly, he makes the movie he himself would like to see. The smart movie executives in Hollywood, the guys with the Harvard degrees where their hearts are, and calculators for brains, they make movies that, “the audience want to see”. How do they know what the audience want to see? Well, they count up box office receipts. So what they ought to be saying is this, “we make the movies that audiences wanted to see last year”. Which is fine, except, audiences don’t really want to see again what they saw last year, do they? They’ve already seen it.

If one can say anything that’s categorically true about what audiences want, it is this. What they’re after is something fresh, something new, something unexpected. No form of marketing analysis can predict that. Even if it could, that would make it predictable. And nobody likes predictable movies. Now listen to what Jackson is saying again: He makes the kind of movie he himself would like to see. What does this really mean? Well, in practice, it means that when he’s writing, he’s finding bits and pieces, ideas large and small that are surprising. This sequence surprised him, this bit gave him a thrill, this bit over there moved him to tears. And all those scenes did that to a guy who has seen thousands of movies. He’s seen it all, yet that script has got him excited enough to spend two, three, or more years of his life making it into a film.

Okay, so lots of us get passionate about what we do. But does the passion of the filmmaker guarantee any kind of satisfaction for the audience? Well, only a track record can tell you that. Jackson’s track record speaks for itself. If something excites him, you’d better believe it’s going to rock your world. After five years of observing from the wings, it’s nice to be able to breathe again. I can’t say I ever really doubted Lord of the Rings would be the huge worldwide smash hit we all hoped it would be, but for me, and for most other New Zealand filmmakers, and maybe New Zealanders in general, what was at stake was more than just a movie. It was something far more important – the idea that if something is truly great, then it will connect. For this proud but isolated and remote little nation, nothing is more important than that we connect with the rest of the world. Short of wars or natural disasters, movies do this better than anything else.

In giving himself something to watch, Peter Jackson has given the rest of us good cause to shake off complacency and start thinking about how to realise a few other ‘impossible’ goals.

Author:

Costa Botes is a New Zealand filmmaker and critic. With Peter Jackson he threw a cinematic dummy to the nation when he co-directed, wrote and produced the memorable mock-umentary, Forgotten Silver, in 1995. In 1988 his short film, Stalin’s Sickle, won the Grand Jury Prize at the Clement Ferrand Short Film Festival, France (co-produced with NZEDGE co-founder Brian Sweeney). He directed the feature film Saving Grace in 1997 (adapted from a Duncan Sarkies play) and most recently completed a documentary on the making of the Lord of the Rings. He has appeared as an actor, putting his body on the line in Bad Taste (see below) and Forgotten Silver and for many years Costa was film critic for Wellington’s Dominion newspaper.

Art for art’s sake? The author (or half the author) in Bad Taste

MAY 2002

This was a great article about an amazing director. I thoroughly enjoyed learning about him during his early years as an amateur, do whatever it takes, filmmaker. Peter Jackson has become something of a legend in his own time and it can be difficult to find some truly great stories that are not written by executives to keep an image legendary. This story felt real and personal. thank you.

Is Peter Jackson still making films about hobbits and giant gorillas? I'd like to see the man with his talents come back to his own country and make a film that would knock the arse out of world, a film about journeys, Captain Cook, Hone Heke, the Maori, the Pakeha settlers, the wars, the missionaries, the great chiefs of both sides, the battle at Kororareka and the Waitangi treaty...This is all actual history. I suppose it's too much. Alright to dream that someone someday might make something real out of what's real though? Noho ora mai.. Tena koutou katoa. Pat Whangarei, New Zealand

I was quite intrigued by your Peter Jackson biography, and of course I'm an enormous fan of his work. Photographer Portland, USA

Dear Editor, If possible, please extend a note of thanks to Costa Botes for his article profiling Peter Jackson, I really enjoyed it. Thank you, Sam Doust. Sam Doust

Thanks to Peter Jackson and everyone else who made the cinematic adaptation of the Lord of the Rings both possible and a success. The care, love, integrity, and respect that all of you share for Tolkien's masterpiece is evident in your first installment, The Fellowship of The Ring. These books brought a lot of joy to me in the sorrow of my early childhood. They are in my heart forever. I watch the DVD all too often and cry every time at the beauty, the elegance, the fragility of life, and the powerful mythology. You have distilled the vital essences of this book like no other adaptation. A heartfelt thanks to all of you. I eagerly await The Two Towers! Service Repairman St Louis, USA