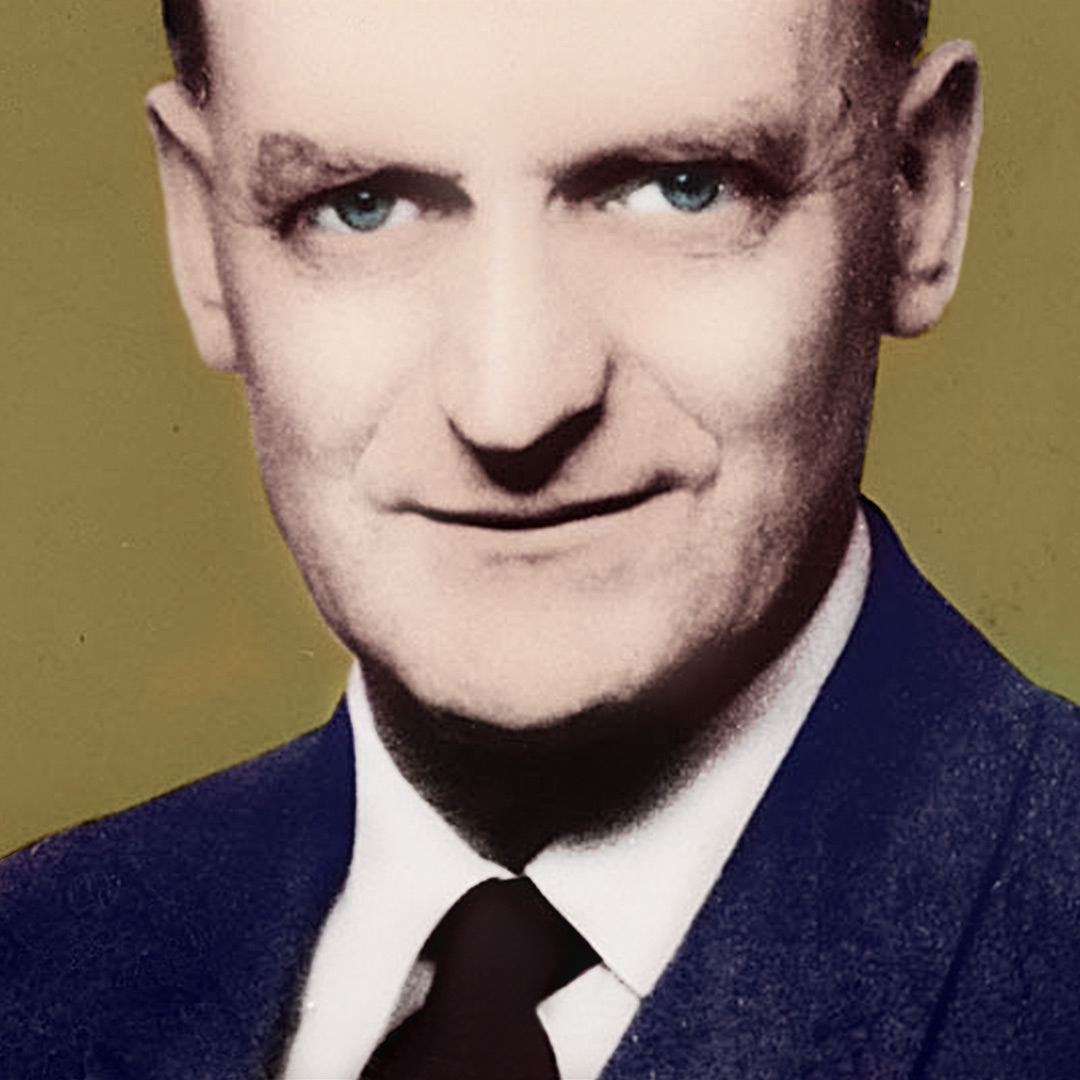

Burt Munro, known as the fastest man from New Zealand, became internationally known for the records he broke at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah in the 1960s. In eleven record attempting trips to the National Speed Week, the Kiwi broke three world records on his Indian motorcycle – one of which still stands today. The “World’s Fastest Indian” from the edge of the world believed in boundless opportunities and in the importance of never giving up his dreams regardless of challenges along the way.

With a speed of 178.971 mph (55cu inch 883 class) Burt broke his first record on the Salt Flats in 1962; in 1966 he set a new National Speed Record with 168.066 mph (61 cu inch 1000 class) and in 1967 with 68 years of age, he broke his final US record with 184.087 mph. 190.06 mph – the highest speed ever measured by any timing apparatus at Bonneville for an Indian motorcycle was also recorded by Burt and his Indian.

No one could put a stop to Burt Munro. He was a resourceful, unconventional motorcycle racer, who constantly pushed his bikes to new speeds, a traveller with many friends around the globe and a curious explorer.

Besides his speed, the Kiwi from Invercargill was known for his “remarkable affinity with machinery”, his “uncanny ability to be able to see through a problem to a workable solution” and the “dogmatic persistence at everything he attempted” as friends recall. His motto was to “fix it and try again”, regardless of how many times something needed to be rebuilt. In 50 years he had around 250 motor blow-ups or other machine failures – some happening with the worst timing just 24 hours before another one of his record attempts.” Burt Munro never gave up nor did he take no for an answer.

Burt told Roger Donaldson film director and his cinematic champion: “I’ve always been working on my bike – even when it blows into hundreds of pieces – I just wade in again and start all over again. I’m happy doing that. If you don’t put an effort in at anything you might as well be a vegetable.”

The documentary “Offerings to the God of Speed” and the movie “The World’s Fastest Indian” produced and directed by Roger Donaldson both are based on Burt Munro’s life. In his book “The World’s Fastest Indian – A Scrapbook of his Life”, Donaldson published excerpts from Burt’s scrapbooks, which he kept in fear of losing his memories due to the concussions he suffered during his career.

“The World’s Fastest Indian” opened in 2005 in Invercargill starring Sir Anthony Hopkins as Burt Munro. Donaldson’s interest into the Invercargill man’s life had been sparked after making the documentary “Offerings to the God of Speed”. From then on it was clear to him that he wanted to produce a blockbuster movie to honour the Kiwi’s life work and his belief that “If it’s hard, work harder; if it’s impossible, work harder still. Give it whatever it takes, but do it”.

The need for speed

Burt Munro was born as Herbert James Munro on March 25, 1899 in Edendale, Southland near Invercargill. In New Zealand the Southlander was known as Bert for his entire life. Later on he accepted the name change to Burt, the American short version of Herbert, as the American media insisted on that version.

When he was born, doctors did not have a lot of confidence in Burt’s survival as his twin sister was still born. Burt, however, already seemed to display the resilient streaks he was known for later and against the odds survived.

His parents owned a farm east of Invercargill and it was here that Burt discovered his love of and need for speed on the back of the farm’s fastest horse. His passion for machinery became visible when at 14 years of age he built a working cannon to protect the farm from the Germans in WWI. He tested it by aiming at a packing case he had positioned in front of the shed. Unfortunately his machinery was more powerful than he had thought and it not only destroyed the packing case, but also the weather-boarding of the shed and hit his father’s drill.

In one of his scrapbooks Burt recalls that his father was not happy about his attempts.

“Dad never swore in his life (…), but he said one bad word when he came home and saw the Pennsylvania drill with one tine missing”.

After the cannon, which Burt had to hand over to the police, during an amnesty in the early 1950s, he built the shell of an aeroplane – a 10-foot long and 10-foot wide biplane. Back then nobody had engines except stationary ones, which is why Burt could not put in an engine and the plane never left the ground. Nevertheless Burt’s passion for machinery was peaked.

In 1915 the farms horses were not enough anymore. The Southland Kiwi bought his very first motorbike – a Douglas, which he rode until he could afford to buy a Clyno with sidecar in 1919. Burt’s father did not share his son’s passion for speed and had hoped for his offspring to learn how to be responsible with money rather than buying motorbikes or parts to be added onto his bikes with every penny he owned.

It was in 1920 that Burt bought the motorbike love of his life – his Indian, which he would ride until his death in 1978. When he purchased the Indian its top speed was around 50 miles per hour. Over the following 45 years of rebuilding and tuning Burt managed to make it go in excess of 200 mph – four times its original speed.

The urge to go faster

An entry of the Invercargill City Council in 1924 shows Burt already was testing the speed limits when he was caught driving “on the North Road at a greater speed than 15 miles per hour”. 15 miles per hour being the speed limit at that time. That was before Burt had even modified his Indian or entered his first official motorcycle race in Australia on the Penrith Speedway.

Burt had worked on his grandfather’s farm until 1919, when his grandfather sold the family’s land. Following that time he took a job in at Arthur’s Pass working on the Otira tunnel. When he received a letter from his father to come home and help on the new farm in South Invercargill, he returned dutifully to help his family.

Apart from speed and machinery, Burt also is said to have been quite a ladies man.

Speaking about what makes life worthwhile to Roger Donaldson, the racing legend said:

“It’s effort and concentration that makes life worthwhile – and nice ladies around are a big help (…) As the guy at the party said: ‘ If there’s no women, there’s no party for me’”.

In 1925 Burt married Florence Beryl Martyn, the sister of one of his closest friends. Together the couple sailed to Australia where his daughter June was born (Rose Bay, Australia) the same year. His second child Margaret also was born in Australia, Glebe two years after that.

In 1926 Burt modified his Indian for the very first time. He “replaced the barrels, pistons, lubrication system, and flywheels with some of his own making (and) also designed a 4 cam to replace the original 2 cam design”. As described in notes to the Te Papa exhibition “A Bike, a Shed, and Burt Munro,” Burt always had been very creative when it came to modifying or fixing his motorcycles. “He made cylinder linings out of cast-iron drain pipes and fabricated con-rods from steel Ford-motorcar axles. To make a flywheel he cut a coin-sized slice from a hydraulic ram, and used a steam-driven hammer to flatten it out to about 180mm diameter… He made high-speed tyres by carving the treads off factory-made racing tyres.”

In the late 1920s when Burt lived in Sydney, Australia with his family he tested the capacity of his newly modified bike on Australian speedways. It was there that he first experienced ‘speed-wobble problems’ and had to jump off his bike midrace.

“I hit one of these rain gutters and the bike shot up in the air. When she landed she got into a speed wobble (…) I knew she wouldn’t take the bend (…) I didn’t want to die till the end of the race at least, so I jumped off the back and let her go” Burt wrote in his scrapbooks.

Some people might have given up racing after that experience. But Burt would not have been Burt if he did not find a way to solve the problem causing the wobble at least temporarily.

When Australia was struck by the Great Depression in 1929 Burt and his family had to return to New Zealand. In the following year Burt started to work as a motorcycle salesman at Alf Tapper’s motorcycle shop ‘Tappers’. In his free time the motorcyclist competed at the many New Zealand beach races on his Indian.

In June 1930 his daughter Lillian Gwen was born and the family moved into a new home, built by Burt on part of the land of the Munro farm ‘Elston Lea’ in Invercargill. Naturally Burt added a workshop for his motorcycles to the property as his passion still was riding the bikes rather than selling them. In 1934 the Munro family was complete with the birth of their son Herbert John.

Burt nearly left his family in 1940 for the Second World War. Following the call for volunteers he went “down to the drill” to attend medical examinations which were part of the selection process. Burt, however, did not get taken as it had been found that a father of four children should stay with his family.

Early Record-breaking years

Over the next years Burt became more known for his constant speed improvements and records on New Zealand beaches and roads. On January 29, 1940 he became the fastest man in New Zealand when he broke the national speed record with 120.8 miles per hour. But for Burt this was still not fast enough though not all races had a happy-ending for Burt. In 1941 the racer suffered a bad accident, which forced him to take a one year break from racing and work. When he returned to Tappers where he would stay for the next four years, he no longer worked as a salesman, but as workshop foreman.

1945 was a year of changes for Burt. Following several small jobs such as working at the waterfront or sawmill for instance, he went into partnership with one of his acquaintances: Mac Tulloch from Mataura. Burt was responsible for truck maintenance and the mechanics of the business, whilst Mac worked on the accounting and business side.

1945 was also the year that the Munro’s family home went up in flames when Burt was in hospital himself recovering from three degree burns from an accident. Beryl had tripped with a pot of boiling caustic soda for soap making and Burt caught most of the pot contents on his chest. Burt went on to immediately rebuild the house which still stands at 314 Tramway Rd. After the fire Beryl left Burt to move to Tauranga and took June, Gwen and John with her; only Margaret stayed with her father as she herself did not want to leave Invercargill.

In an interview with Roger Donaldson Margaret told him how proud she had been of her father.

Burt on the Munro Special in front of his shed at 105 Bainfield Road, Invercargill – Permission Munro Family Collection

“I feel very proud of Dad and what he has accomplished. I know (dad) is always breaking down, but he’s very happy working away (…). He goes out and blows up an engine and it keeps him busy for weeks – he’s very happy, he really is.”

Burt’s business partnership disintegrated three years later as it seemed he was more interested in his bikes than the business with Mac. According to his friend George Begg this was only one of many differences in the partnership, starting from when Burt arrived three months late for the starting date of the job itself.

The loss of job did not devastate Burt. He decided to finally do what he loved and only concentrate on modifying the two motorbikes he owned at that time: The Indian and a 1936 Velocette. With the additional time spent to modify his bikes, he quickly got back into serious competitions.

When his father passed away in 1949 Burt bought half of his parents’ farm property and built a racecourse, where he would test his motorcycles. In 1951 Burt purchased new land on Bainfield Road, Invercargill. Burt had very clear ideas as to how his new home should look. However it seems that the Council had problems with his vision. “At the time the council had a stipulated minimum stud height of eight feet in a domestic dwelling”, as described in Tim Hanna’s One Good Run: The Legend of Burt Munro. Burt wanted to build with a height of seven feet as otherwise he would have to pay for extra heating. In addition to that he wanted to save bricks by placing them “with their thin sides in the vertical position”. His requests got declined, which is why Burt settled for a single car garage where he lived and worked from then on. This garage was the maximum size of 20 x 10 feet allowed by post war building regulations.

Margaret told Roger Donaldson that she “used to worry about him living in that shed (but…) he didn’t spend the winters there – he would go away to the States about April or May each year and come back around November. He missed the colder parts of the winter.”

Burt lived and worked in his shed. Motorbikes were his life after all. Used parts of motorbikes were lined up on a shelf, which he called “Offerings to the God of Speed”.

Murray Thwaites – one of the kids of the neighbourhood, who used to watch the bike enthusiast work in his shed – remembers his visits in an interview with The Times New Zealand.

“He lived in the garage which always smelled of engine oil. There was an old couch we used to sit on – the Indian bike was in the middle and the shelves were full of parts of all kinds.”

Ian Johnston, another one of the kids who spent his time at Burt’s shed told Roger Donaldson:

“I always had confidence in Burt and thought of him as the nicest, kindest man in the world. He never grumped at me (…) and I wasn’t too fussed on him patting me on the head with his greasy old hands”.

Burt’s Indian, 1953, before attempting a New Zealand beach record – Permission Munro Family Collection

In the same year of 1951 Burt raced at the NZ Open Beach Championship on December 8 at Oreti Beach. His speed was incredible and he was the fastest racer. However, he was unable to turn the Indian quickly as it did not have proper brakes. Despite advice from others Burt did not want to improve his brakes. It was about being quick after all, and not about stopping.

From then on record after record flew Burt’s way. In 1953 he and his Indian raced to 124.138 mph at the NZ Beach Open Capacity Flying Half-Mile, which he would raise to 131.380 mph on February 9, 1957.

In 1955 Burt decided that it was time for him to travel the world. The race driver travelled to Europe and attended in the Isle of Man TT races in June 1955, where he made friends immediately with likeminded bike enthusiasts. Wherever he went people seemed to be fascinated by the fast New Zealander and his unique approach to life. Burt spent three months travelling around with Australasian racing friends before returning to New Zealand via USA in October 1955.

From then on the travel bug had truly bitten Burt. In 1957 he left New Zealand again to travel to the famous salt flats at Bonneville, Utah in the United States. He was accompanied by the two world record breakers Russel Wright and Bob Burns when he fell in love with America, its people, its culture and of course the Salt Flats in Bonneville.

The American Years

After raising the record for the New Zealand Road Speed 750cc class to 143.59 mph on April 13 1957, Burt decided that it was time to travel again and in the following years he followed his passions – travel, racing and the United States.

Burt made many friends on his countless trips to America – one of them Marty Dickerson. Speaking to Roger Donaldson, Marty recalls a conversation with Burt about his health.

“He had a heart problem and didn’t feel good. So he went to a hospital, and they said, ‘Oh, your heart is bad. We got to keep you here – keep tabs on you’ and Burt said ‘How much?’ and the guy told him – $14 a day – and Burt said ‘Bloody hell, that’s too dear. If I’m going to die, I’ll go die in my car.’ ”

Typical for Burt, he waited until he felt better and then simply kept on driving according to his friend Marty.

Burt continuously competed with his motorbikes and on December 16, 1961 he set another record of 129.078 mph for the under 750cc Flying Half Mile Beach Record. In the subsequent ten years Burt was able to raise that record to 132.32mph and also won the standing ¼ mile sprint in Timaru, New Zealand with just 13.1 seconds.

Having seen others compete at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah at the National Speed Trials Burt thought it was about time that he himself would ride on the Salt Flats in 1962. According to his friends he initially did not have the dream of breaking the record, but simply wanted to race on the famous track. So he packed up his things and travelled to the USA with the same bike – the same Indian he had bought in 1920. This was to be the first of his eleven record-attempting trips.

Every other person would have probably given up when encountering the challenges Burt did when he arrived in the United States – but not Burt. As described in George Begg’s book “Burt Munro: Indian legend of speed”, the New Zealander was told that he would have to pay 10,000 USD bond in order to import his bike into the States when he went to pick up his bike in Seattle. There was no way Burt was able to pay such a huge amount before even having started to compete. It was then that the typical Burt Munro luck struck and Mr McPherson, a solicitor, took on Burt’s case for free. Somehow he managed to bypass the fee and Burt could travel towards Speed Week.

This, however, did not remain the only obstacle the fastest Kiwi had to face as many of Burt’s friends recall inter alia George Begg in his book “Burt Munro: Indian legend of speed”. Steep hills paired with a cheap used car and a trailer on which the Indian was fastened made his journey difficult. One time the spring catch on the bonnet let go and flew up so that Burt could not see anything in front of him. Another story has that Burt saved the brakes on his car by opening the doors as natural brakes to not run them down. However, what was most remarkable about Burt’s journeys, was that no matter what happened to him, Burt always found a solution and never gave up.

The Bonneville Salt Flats

“I guess I am a fanatic or an enthusiast. I have been called a super-enthusiast, working on my bike for so many years – I think if a thing’s worth doing, it’s worth finishing if you can. Lots of people ask me when I’m going to give it up (and) I say ‘I’m never going to give it up till I get a good run” Burt said about himself.

Burt was the first to arrive in Wendover in 1962, which was close to the Salt Flats: He was all set to start.

The Salt Flat Speed Week always had a lot of willing participants waiting to compete. Therefore racers had to qualify as high-speed racers and undergo a pre-race check in order to be allowed to run for. When getting his bike checked Burt encountered another obstacle resulting from his unconventional bike building and modifying methods.

Burt Munro with Rollie Free(cigar) and Marty Dickerson (camera) – Permission Munro Family Collection

He was told by his friends Marty Dickerson and Rollie Free that his tyres would never be allowed on the race course as “the cords were showing” in some places. Burt knew he did not have a lot of time to modify or change his tyres which is why he made sure that the tyres were positioned in a way that the inspectors could not see the cords showing. Miraculously it worked: To the amazement of his friends Burt passed the inspection and was ready to go.

The first test run on the salt was supposed to show that a racer could control his bike. Burt experienced a bad speed wobble on the salt and thought that he would be excluded from the competition. Again he was lucky: No one seemed to have realized and Burt got the permission to start, qualifying as a high speed bike with 174.75mph. Then it got serious.

When Burt and his Indian were underway on their first record attempting run, the “tank slapper” came back and got stronger and stronger. Stopping was out of the question for Burt. It was “all or nothing”. So he kept going. Salt was constantly being thrown up against his goggles. That blocked his vision and Burt lost his sense of direction. He could not see where he was or where he was going. Was he still racing in the right direction? Still stopping was no option.

When the bike stopped as its wheels hit soft salt Burt had already gone past the nine-mile marker. He had no idea how his run had been and had to fix up his bike before he could go for the return run. Luckily he got help quickly and after securing a wheel and cleaning his goggles he was ready to go back. Again nothing was easy.

Burt forgot to pull up his landing gear and it seemed that he lost control over his bike. Everybody thought he would crash. Burt Munro, however, did the unthinkable. He got his Indian under control and set off again to break a record.

The New Zealander was not too familiar with the race course, which is why on that return run, he got confused by the now descending mileage boards. Burt thought he was already closer to the end than he actually was. He was not one to give up, so he opened the throttle and went as fast as his motorcycle would. His Indian already had been strained from the high speeds and going even faster now was an additional strain on the engine. Nobody knew what had happened when Burt didn’t return to the starting line.

Marty Dickerson remembers the moment he and Rollie Free, Burt’s pushers, went looking for Burt in conversation with Roger Donaldson.

“We couldn’t find Burt anywhere – he was nowhere in sight. That’s when Rollie said (…), ‘He’s gone back – back to whatever planet he came from, because he sure as hell ain’t from this one!’”

When he finally was found Burt was lying in the shade trying to cool off. He had burnt his leg on the exhaust pipe. The burn itself was not reason enough for Burt to stop though. His Indian had run out of fuel because he went too fast for too long and so they finally stopped.

When the Kiwi returned to the base, he was surprised to hear that he had indeed broken the record for 55cu inch displacement (883cc) bikes with a speed of 178.971 mph. Burt was not entirely satisfied with that result and still wanted to keep competing over the course of the week, because he knew the Indian could go even faster.

Burt, 1962, after being given the Sportsman of the Year Award in Bonneville- Permission Munro Family Collection

He knew, however, that repairing his bike would be costly. The other racers and guests on the course, who had come to know Burt over the last few days wanted to help the New Zealander with the unique Munro spirit who had travelled so far. They did not hesitate to award Burt with the Sportsman of the Year Award, for which he received 350 USD. With that it was settled: Burt could stay.

Burt spent the following days repairing his Indian. He tried to find the reason for her weaving, but when racing again, the problem was still there and his bike spun completely out of control.

Burt recalled the incident.

When my friends got down there I was laughing like hell and they wanted to know what I was laughing at. I said, ‘Well, I should be dead long ago, but I’m so pleased to be alive I can’t help laughing!’”

One of the guys present, an air force officer made a remark, which according to Burt “saved (himself) twice later.”

The air force officer told the New Zealander that he had “shifted the centre of gravity back and that made (the Indian) go straight”. Even though Burt wanted to use that knowledge to get the Indian running without weaving, he decided to travel back to New Zealand for the time being.

Burt Munro’s Indian at the Salt Flats stripped of its streamliner shell – Permission Richard Menzies

Return to the Salt Flats

From 1963 until 1966 Burt spent his time modifying his Indian and travelling back and forth between America and New Zealand by ship. He streamlined the Indian’s shell and rebuilt its entire motor. As the bike was not suitable for riding on the beach anymore Burt did not test drive it with its modifications until he arrived in America again. Luckily he still had his Velocette, which he rode extensively whilst in New Zealand.

When he arrived at the Salt Flats in 1963, Burt qualified with a remarkable speed of 183.673mph. Some even say that he was going 195mph at one point. Unfortunately the Indian’s motor had enough and blew up so that Burt did not have any choice but to travel back to New Zealand. In the years after that it seemed that Burt’s luck had run out. Every time he tried to break another record heavy rainfall made the salt unsuitable for races and he was forced to cancel his plans or even travel back to New Zealand without even riding his motorbike on the Salt Flats.

On August 22, 1966 after enlarging the bike’s capacity to 61 cu. inch 1000 class Burt could finally compete again. In the race Burt pushed the Indian to its limits. The bike was shaking at his tremendous speed of 200 mph. Just like on his previous runs, he lost orientation. Again salt had been thrown up in front of him from his shaking tyres. He broke the National Speed record – 61 cu inch 1000 class with an average speed of 168.066 mph. Now that Burt knew for sure that his Indian was able to go as fast as 200mph or even more, there was no stopping him.

Determined to show the world how fast his Indian could go, he continued to work on the bike, whilst competing with his Velocette all around New Zealand.

In 1967 Burt found that he was ready: It was time again to travel to America. As usual things weren’t easy for the Kiwi rider. This time one of the Indian’s pistons blew up during his qualification ride, where he recorded 184 miles per hour. As a result he could not go for the record before fixing his beloved Indian.

Unfortunately it seemed that Burt’s luck had not returned fully when in his second qualifying run the Indian’s clutch gave him grief. Again – he could not repair the bike in time to have a go at the record 24 hours later. Burt didn’t give up.

He opened up his bike again only to find that the Indian’s valves were ruined and that he would need new ones. Burt could not afford to buy new valves, so he collected every valve he could find and finished repairing his bike just in time to go for his final qualifying run. Burt on his Indian qualified with an incredible 190.06 mph. Burt knew his Indian could go higher; he just had to prove it.

In the next attempt Burt pushed his Indian to its limits. With 183.586 mph he broke the SA– 1000 class record, which he still holds today. According to his friends Burt was still disappointed as he had wanted to prove that his Indian could go 200 mph.

In 2014 his son John discovered a mathematical error had been made when calculating the average speed in August 1967. Instead of the recorded 183.586 mph, Burt’s average speed had been 184.710 on his North Run and 183.463 on his South Run.

In the same year, 1967, Burt was voted the American Motorcyclist of the year. He was 68 at that time.

Last visits to Bonneville

Even though Burt’s heart problems seemed to get worse he did not take it easy following his record runs. He is said to have tested his health by running up an escalator going down – if he could beat the escalator he was still fit to go for races. In June 1968 he had travelled to the Salt Flats again. A storm made a race impossible and caused the Speed Week to be delayed. When Burt finally was able to compete, he experienced engine problems and again had to hold off and fix his bike. This time nothing seemed to help and the Indian was running comparably slow, so Burt decided to say goodbye to 1968 and try again in 1969.

The Southland Times, the local Invercargill paper, recorded that Burt had to take his first driving test in his entire life at 70 years old in 1969. As expected the

Burt, 1969, in front of his shed with his “wee friends Denise L & Heather Butler” and his 1936 Velocette – Permission Munro Family Collection

motorcycle enthusiast passed with flying colours and everything was set to return to the Speed Week.

Burt had high expectations to both himself and the Indian. It was time for another record. This time things went surprisingly smoothly and Burt broke the record for the highest speed ever recorded by any timing apparatus at Bonneville or anywhere else for the Indian Munro Special with 190.06 mph.

Even though Burt felt he was getting older, he wanted to attempt another record at the Speed Week one last time. In America, he was talked into trying new fuel for his Indian – nitro based fuel, which was quite common at that time. However it seemed that the Indian’s old-fashioned pistons were unable to deal with the modern fuel and piston after piston blew up and Burt ultimately had to give up on his record attempts in 1970.

1970 became the year when Burt’s life was recognised the most with a plague from New Zealand Auto Cycle Union honouring his contribution to Motor Cycling. In the same year he was approached by Aardvark Films and its producers Roger Donaldson and Mike Smith who wanted to produce the documentary “Offerings to the God of Speed” and later on were responsible for the movie “The World’s Fastest Indian”.

In 1971 Burt took the documentary film crew to the Salt Flats as he wanted to show them how it was done himself. However when attempting his ride, his bike did not run well as he had to change the shell of his Indian because of last-minute rule changes and he was not able to demonstrate what he and the Indian could do for the film crew. Regardless the “Offerings to the God of Speed” aired on NZ Television in 1973.

Roger Donaldson remembers the first time he met Burt Munro.

“We (were) greeted by a scruffy elderly gentleman with a wicked twinkle in his eyes and a broad, winning smile. Burt made them a cup of tea using the water tank on the outside of the shed. A few minutes later he used the same tank to thrust a hot piston into. With a big chuckle Burt replied ‘Yeah, gives the tea a nice taste of titanium, doesn’t it?”

From then on Burt took things a bit easier. After all these years he built a house next to his work shed and was keen to enjoy life. Taking life easy did not mean, however, that Burt stopped riding his motorbikes. In 1975 he broke another record with an average speed of 136.15mph on the New Zealand beach, for the first time in four years.

In July 1975 Burt Munro travelled to America for the last time. He had made many friends on his 14 visits to the Bonneville Speed Week. He wanted to visit them. He had brought his bike and wanted to have one last run. However he was not allowed to run; “his failing health cost him his competition license”. It is said that only by his return from the USA he moved into his new house, as if now it really was time for him to rest. He had accomplished and done what he had wanted.

Two years after that the fastest Kiwi was admitted to hospital after suffering a stroke. Even though he recovered well, Burt Munro passed away in January 1978 and left behind his four children and many grandchildren.

In an obituary published in the Speed Week’s official programme Frank Oddo writes:

“Burt Munro was one of those people, who has been most everywhere, done most everything and enjoyed the entire game of life to the fullest.”

His record-breaking Indian was handed over to a local motorcycle enthusiast and is now on permanent display with the Offerings to the God of Speed at E Hayes & Sons store in Invercargill.

Remembering Burt Munro

In addition to Roger Donaldson’s acclaimed movie “The World’s Fastest Indian”, Burt Munro has been honoured with many exhibitions in New Zealand museums such as TePapa and the Southland Museum & Art Gallery.

Te Papa also holds one of two replicas of Burt’s record-breaking Munro-modified Indian used in the making of ‘The World’s Fastest Indian’.

In 2006 “the legend of motorcycle speed demon” was entered to be eternally remembered in America – in the American–based Motorcycle Hall of Fame. “It’s pretty amazing, quite a privilege” said Burt’s son John when he was told about the honour. “There’s a lot of famous names at the museum, but he’s the only New Zealander here”.

Those who love speed can also relive and honour Burt’s achievements when taking the Burt Munro Challenge in Invercargill, which has been named one of the 5-must do events in 2013 by Time Magazine. “Like its eponym, the Burt is unique, combining seven forms of racing: beach, circuit, street, long track, sprint, hill climb and speedway. Throw in live music, food, camping and Invercargill’s famous hospitality, and you’ve got one of the most colourful motorsport festivals ever conceived”.

In 2011 Polaris Industries bought the brand, because they wanted to build something to commemorate the Kiwi racer, Burt’s son John recalls in an article on stuff.co.nz: The Spirit of Munro was born. The machine was built by hand “by Jeb Scolman of Jeb’s Metal and Speed in Long Beach, California. It was designed from the ground up to house the new Thunder Stroke™ 111 engine and showcase its awe-inspiring power and performance.”

On behalf of his friends Frank Oddo wrote in his obituary “Even though most of his life was well spent some ten thousand miles away, he touched ours more than a little. We’ll never forget him.”

The Quotable Burt Munro

“You can live more in five minutes on a motorcycle in some of these events I’ve been in than some people do in a lifetime.”

“I’ve always been working on my bike – even when it blows into hundreds of pieces – I just wade in again and start all over again. I’m happy doing that. If you don’t put an effort in at anything you might as well be a vegetable.”

“If it’s hard, work harder; if it’s impossible, work harder still. Give it whatever it takes, but do it”.

“I guess I am a fanatic or an enthusiast. I have been called a super-enthusiast, working on my bike for so many years – I think if a thing’s worth doing, it’s worth finishing if you can. Lots of people ask me when I’m going to give it up (and) I say ‘I’m never going to give it up till I get a good run.”

Our thanks and appreciation to John Munro, Burt’s son, for his time and contribution, and for the use of family photos.

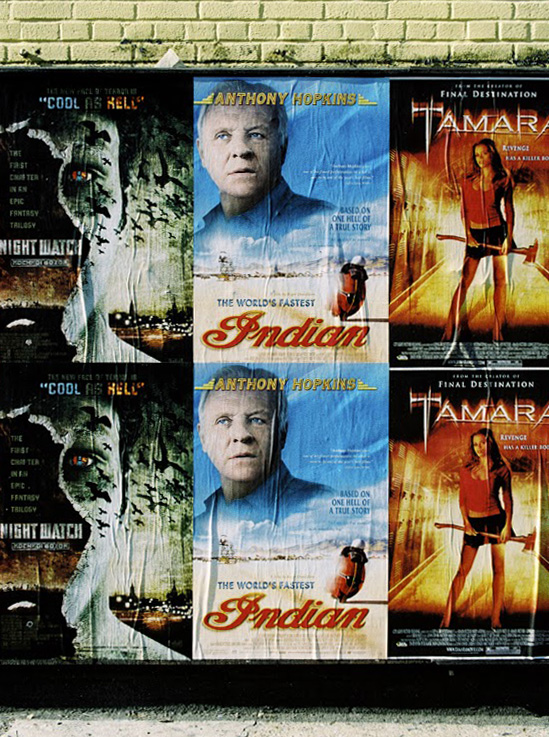

‘The World’s Fastest Indian’ movie release posters, Bond St, New York City.

Photo Brian Sweeney, 2005

References

Films & Documentaries

Roger Donaldson (2005). The World’s Fastest Indian, Magnolia Studios, New Zealand.

Roger Donaldson (1971). Burt Munro: Offerings to the God of Speed, Aardvark Films, New Zealand.

Web Sources (accessed March 2015)

From TePapa, Museum of New Zealand “A Bike, a shed, and Burt Munro”

http://www.tepapa.govt.nz/WhatsOn/PastEvents/WFI/Pages/Burt.aspx

From New Zealand Tourism, “Burt Munro – a Southland speed legend”

http://www.newzealand.com/int/article/burt-munro-a-southland-speed-legend/

From New Zealand Tourism, “The World’s Fastest Indian”

http://media.newzealand.com/en/story-ideas/the-worlds-fastest-indian/

From the EHayes Motorworks Collection, ‘The World’s Fastest Indian”

http://www.ehayes.co.nz/Hayes-Motorworks-Collection/Burt-Munro-__I.517

From the Times, “Who watered Burt Munro’s lemon tree?”

http://www.times.co.nz/2006/who-watered-burt-munros-lemon-tree.html

From GearPatrol, “The Story of Burt Munro”

http://gearpatrol.com/2013/05/13/the-story-of-burt-munro/

From SouthernScoot, “Burt Munro”

http://southernscoot.co.nz/burt-munro/

From Indian Motorcycle, “The Spirit of Munro Streamliner”

http://www.indianmotorcycle.com/en-us/stories/munro-streamliner-photos

From Invercargill.co.nz, “Burt Munro Challenge”

http://www.invercargillnz.com/Events/Burt-Munro-Challenge

From AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame, “Burt Munro”

http://www.motorcyclemuseum.org/halloffame/detail.aspx?RacerID=381

From Motorcycle USA.com, “Burt Munro breaks record 36 years after death”

Newspaper and Magazine Articles

Knight, Kim (2004). Indian Summers, Sunday Star Times, November 14.

Cheng, Derek (2006). Burt Munro to join Hall of Fame, The New Zealand Herald, June 05.

The Times (2006). Who watered Burt Munro’s lemon tree?, The Times Newspaper New Zealand, August 17.

Book Sources

Begg, George (2004). Burt Munro: Indian legend of speed, Begg & Allen, Christchurch.

Donaldson, Roger (2009). The World’s Fastest Indian – Burt Munro – A Scrapbook of His Life. Random House, New Zealand.

Hanna, Tim (2005). One Good Run: The Legend of Burt Munro, Penguin Books, Auckland.

Sell, Bronwyn & Sheehy, Christine (2014). The greatest underdog stories in New Zealand Sport. Allen & Unwin, Auckland.

Williams, Tony (2006). 101 ingenious Kiwis: how New Zealanders changed the world, Reed, Auckland.

Wright, Matthew (2009). 100 wonders of New Zealand engineering, Random House, Auckland.

True I was for fteen on first bike I can do atertude if your horses thou you get right Bk on first never think about be for or be put off what other say in the name god s rule s life to succeed