“To no woman has it been permitted to do the same amount of good, and to save more misery and suffering, both during and after the war, than to Miss Ettie Rout. . . . Not only has Miss Ettie Rout the qualities that characterise all great humanitarians, but she also possesses, in a unique degree, an intimate knowledge of the terrible troubles that arise from intercourse, and of the manner in which they can be reduced and perhaps eliminated.”

Sir William Arbuthnot Lane, Consulting Surgeon to Guy’s Hospital, London, 1922

Reviled and lauded in equal parts, Ettie Rout was a woman before her time, a career woman in pre-World War I Christchurch, and then a tireless campaigner in the war to prevent venereal disease – one of the main reasons for the hospitalization of Australian and New Zealand troops abroad. Coming from the edge to help “our boys” abroad, she became recognized as a key thinker and worker in a fight with which all Europe was concerned.

An independent woman

Ettie Rout was born in Tasmania in 1877 and moved to Wellington with her family in 1884. She won a scholarship to Wellington Girls High School in 1891, but was unable to take it up, as her father had gone bankrupt and Ettie had to support her family.

In the mid-1920s, with her Remington typewriter. Frontispiece to her later book, Maori Symbolism (1926).

Ettie was a woman ahead of her time in turn of the century New Zealand. She was a career woman: a teacher, a journalist, and a court reporter who started her own shorthand typing firm. A committed socialist, she campaigned for equal pay, health issues and labour issues, and founded the labour magazine, The Maoriland Worker.

A new struggle

When World War I began, Ettie was in her late thirties, a tall, determined woman with a public profile as an advocate for women’s equality and physical fitness. As New Zealand men began to volunteer for active service, Ettie saw a way for New Zealand women to contribute. In 1915 Ettie set up an organisation, the New Zealand Volunteer Sisterhood. She advertised for able-bodied women between the ages of 30 and 50 and filled her quota of 10 volunteers within hours.

Ettie with her Volunteer Sisterhood, Oct 1915. Ettie is the one in the centre without a hat. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any re-use of this image. Ref. no. 1/1-014727-G.

First, the volunteers spent a month training and helping with a cerbro-spinal meningitis epidemic. However when they were ready to leave for Egypt the Government decided that the Volunteer Sisterhood should not go overseas. The Christchurch Press also started a campaign against the Volunteer Sisters, declaring that having New Zealand women doing work usually done by Egyptians would lower the prestige of the “white race”. Despite this, Ettie was determined, and the women found their own sponsors. As Ettie wrote in a handbill advertising her mission:

“We women of New Zealand are organising ourselves in a Volunteer Corps ready to help the sick and wounded. We want no payment for this work – just sufficient money to provide us with the bare necessities of life – food, clothing, shelter. Will you give us these? We give ourselves.”

The first contingent of the Volunteer Sisterhood left by ship in October 1915 in defiance of a horrified Minister of Public Health, who only learned of the event from the newspapers. Ettie and more Volunteer Sisters set off in 1916, and by 1917 the women who had gone to North Africa had all found work in hospitals and canteens. It was time for Ettie to move on to a new task – one which would make her an even more controversial figure.

Wicked woman or guardian angel?

Working in Egypt, Ettie had discovered the extent of venereal disease among the New Zealand and Australian troops. It was a secret kept shamefully hidden. Official estimates put the percentage of New Zealand troops who had contracted venereal disease at 20%. The real rate was possibly as much as double that: higher than the percentage that actually died in the war.

The traditional ways of dealing with this problem were either to ignore it, or for army medical officers to call on soldiers to practice chastity. There were also networks of women’s patrols: women would walk the streets in London and Paris and intervene when they saw soldiers consorting with girls, telling the soldier not to give in to temptation and trying to get the girl on a homeward-bound bus. Ettie saw such societies as dangerously ineffectual, condeming the kind of woman who got involved with them as:

“the nice well-meaning-motherly woman, half-angel-half-idiot, who specializes in “rescue work”. These women know nothing of the conditions of active service, nothing of the nature and physiology of soldiers.”

Angered at the lack of official response to such a preventable problem, Ettie launched a letter-writing campaign to publicise the issue in New Zealand. She sent a barrage of letters to newspapers, Members of Parliament and anyone else she could think of, until her letters were banned from publication. She realised that practical help was required.

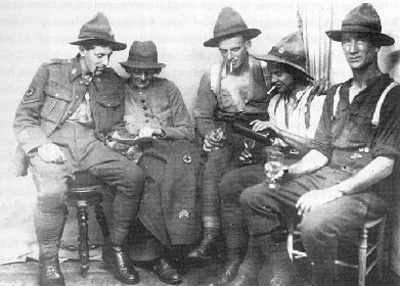

Ettie with soldiers in Paris around 1918. Courtesy Archives New Zealand, Te Rua Mahara o te Kãwanatanga, Wellington Office. Ref. no. WA 10/3/2 zmr 1/1/40

Ettie drew on the advice of doctors and of soldiers and put together a prophylactic kit containing calomel oitments and condoms to be handed out to troops on leave. Finally, at the end of 1918, Ettie received some response to her efforts when the army adopted her kit for free and compulsory distribution. She never received any credit for this.

Her next task was to set up a clean brothel – something the army would have liked to have done themselves but could not be publicly seen to encourage. She knew that calling for chastity was not the answer to reducing venereal infections: better to ensure that the brothels themselves were safe and clear of disease. As such an endeavour was illegal in London, where venereal disease was in fact at its most widespread, Ettie went to Paris.

Ten percent of New Zealand soldiers on leave were bound for Paris, where registered prostitutes, filles publique, were vastly outnumbered by up to 70,000 casual streetwalkers, the filles de joie. Ettie set herself up at the New Hotel opposite the Gare du Nord and from there ran a complete social and sexual health service. When the trains came in from the Front, Ettie would greet each ANZAC with a kiss and bring them to her Centre, where they were given a safe-sex kit if they did not already have one, and received free advice on the dangers of unprotected intercourse. At the same time Ettie persuaded Madame Yvonne to make her brothel clean and she told soldiers to go there. She also contacted as many individual prostitutes as she could, telling them that it was their duty as Frenchwomen not to spread disease that might endanger ANZAC troops.

Ettie is remembered with great affection by many of the soldiers she met and helped yet her actions and her matter-of-fact response to venereal disease made her an object of infamy in New Zealand and overseas. She was called “the wickedest woman in England” by a bishop in the House of Lords and raised outrage in New Zealand among politicians, moralists and the press. All this she took in her stride, treating the New Zealand response to their most scandalous woman as something of a joke. She was also sanguine about how much progress she was making, writing to supporter H.G. Wells (who called her “that unforgettable heroine” in one of his novels):

“I stand with one foot on a hot brick and the other on the thin ice, so progress is rather slow.”

Persona non grata

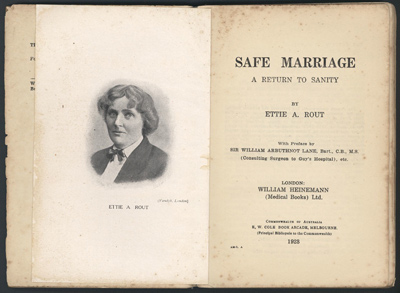

After the war, Ettie lived in England, married Fred Hornibrook, and published books on safe sex and health. However she was still persona non grata in New Zealand: her most popular book Safe Marriage (1923), which went into multiple editions in Britain, was banned in New Zealand. She also wrote on vegetarianism and published what is now regarded as a largely inaccurate book on Maori culture (following her own interest in eugenics and physical health, she praised Maori as eugenicists).

Frontispiece to Safe Marriage (1923). Because of the ban when it was published, Safe Marriage is still very difficult to get hold of in New Zealand. Image supplied by Waikato University Library.

Ettie returned to New Zealand in 1936 after her marriage had broken up but was shunned by former friends and colleagues. She realised that there was no role for her here and left for Rarotonga. After several months she sent out telegrams saying simply “Ettie Rout died at sea” and boarded a ship where she took an overdose of quinine.

Ettie Rout was 59 when she died in 1936. She was recognised overseas by English reformers and French doctors (one of whom called her the “guardian angel of the ANZACs” ), and awarded the Reconnaissance Francaise Medal by the French. The British War Office sent her a tribute via King George V for her contributions to the health and safety of the troops. The Australian official history of the war mentioned her twice. Yet she received no recognition from New Zealand. On her death, the Press Association wrote that she was “one of the best known New Zealand women” but could not bring itself to say how she had earned her fame.

Ettie Rout finally received some public recognition in the naming of the NZ Aids Foundation Ettie Rout Centre in Christchurch. The centre carried her name from 1985 to 2003. In 1992 Jane Tolerton’s superb biography, Ettie: a Life of Ettie Rout, won the New Zealand Book Award for Non-fiction, once again making Ettie a well-known, and still edgy, name in her home country.

We are grateful to Jane Tolerton for reviewing this story.

REFERENCES:

Arbuthnot Lane, Sir William. Preface to Safe Marriage: A Return to Sanity by Ettie Rout. London: Heinemann, 1922.

Keen, Suzanne, “Ettie Rout: Guardian Angel or Wicked Woman?” The Press, 9 September 1992, p.17.

Lanniaux, Karine. “The French Experience: New Zealand soldiers in France during the Great War.” In Antipodes 3, 1997. pp. 32-70.

Tolerton, Jane. Ettie: a Life of Ettie Rout. Penguin: Auckland, 1992.

Tolerton, Jane. “Our Sisters Overseas.” More, April 1988, pp. 142-9.

Tolerton, Jane. “Safe Sex Saint.” The Listener, 1 August 1992, pp. 26-30.

Tolerton, Jane. “A Guardian Angel with a Wicked Streak.” The Dominion, 17 August 1992, pp.8.

Tolerton, Jane “Campaigner Ignored in her own Country.” The Dominion, 13 April 1993, pp.13.

Web Sources:

Read Jane Tolerton’s entry on Ettie in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, updated 7 April 2006. This provides a summary of what’s in Tolerton’s award-wining book on Ettie. http://www.dnzb.govt.nz/

See NZ History Online for a short account of Ettie’s war activities. She is honored here in one of the site’s “Gallipoli Biographies” http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/media/photo/ettie-rout

Try the Wikipedia entry on Ettie http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ettie_Annie_Rout

Browse Ettie Rout’s most popular book, Safe Marriage: A Return to Sanity (1922), available freely at Project Gutenberg http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/16135

Further Reading:

Anderton, Jim. Unsung Heroes: Portraits of Inspiring New Zealanders. Auckland: Random, 1999. pp. 89-107.

Levine, Phillippa. Prostitution, Race and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire. New York: Routledge, 2003.