“McCahon was the artist who gave New Zealand a powerful visual identity and for that he is revered in his homeland. That he went further, to explore and communicate through the medium of painting the universal questions and concerns of humanity, is why we, in other parts of the world, must recognise him as a great modern Master.”

– Stedelijk Museum director and veteran director of the Venice Biennale, Rudi Fuchs, Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith, 2002

Colin McCahon is the most celebrated New Zealand painter of the 20th Century and arguably New Zealand’s greatest artist. His explorations on canvas of his relation to the world and his standing place in New Zealand, squinting into the hard sun, represent defining statements about what it means to be ‘from here’. To paraphrase Australian writer Murray Bail, McCahon reconceived Aotearoa, the land of the long white cloud, as the land of the long black shadow.

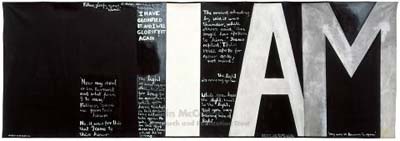

Landscape theme and variations, 1963 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

“They [Landscape theme and variations, 1963] were painted to be hung about eight inches from floor level. I hoped to throw people into an involvement with the raw land, and also with the raw painting. No mounts, no frames, a bit curly at the edges, but with, I hoped, more than the usual New Zealand landscape meaning … I hope you can understand what I was trying to do at the time – like spitting on clay to open the blind man’s eyes.”

Southern education

Born in Timaru on 1 August 1919, the second of three children, Colin McCahon grew up in Dunedin. His father, John, was a commercial traveller and later a company manager, while his mother, Ethel, was the daughter of William Ferrier, a professional photographer and landscape colourist.

Colin McCahon (back right) with (from left) sister Beata, brother Jim, mother Ethel and father John, c. 1939. Photograph reproduced by permission of the Hocken Library, University of Otago.

In 1930 the McCahons moved to Oamaru: “A fine place to be. There were school plays, Saturday mornings on the harbour dredge, rafts on the lagoon. I remember also a parachutist whose parachute failed to open and the white cross erected against the low North Otago hills where he fell.” The dichotomy of the high and the low in this remembrance (the joyous nostalgia for childhood pleasures marred by a tragically vibrant image in the landscape) is characteristic McCahon. In Oamaru he attended “one grateful year” at Waitaki Junior High, before the family returned to Dunedin and he was enrolled at Otago Boys’ High School, a place he called “the most unforgettable horror of my youth”.

In 1936, aged 17, he happened upon a small exhibition of work by the young New Zealand artist Toss Woollaston, and was strongly influenced by Woollaston’s fresh and expressive approach to the landscape. Woollaston (1910-1998) was a pioneer of the modern art movement in New Zealand and McCahon found his works: “wonderful and magnificent interpretations of a New Zealand landscape; clear, bright with New Zealand light, and full of air.”

That same year, after a “long and dismal struggle with my father”, McCahon convinced him to let him study art and he left high school to attend King Edward Technical College. From 1937-39 he studied part-time at the college’s art school, spending the summer terms in Nelson working on orchards.

Here, at the edge of the world, inspired by Woollaston’s work, amidst a gloriously dour Dunedin, far from any international centre or tradition, surrounded by the open terrestrial potential of the Otago hills, McCahon was imbued with his art (“a love of painting and a tentative technique”). The rest of his life was to be dedicated to its application; to seeking a way of seeing.

From the beginning McCahon’s work was provocative. In 1940 the Otago Society of Arts (of which McCahon was a member) refused to hang a painting of his, Harbour Cone from Peggy’s Hill (1939). The society’s conventional good taste was challenged by McCahon’s modernist style which reduced the volcanic cones of the Otago Peninsula to a topographic series of bare, almost monochromatic forms. The protests of other young artists, who withdrew their works in sympathy, forced the society to relent and display the work.

Harbour Cone from Peggy’s Hill, 1939 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

Nelson and Canterbury

In 1942 he married one of the artists who had protested on his behalf, Anne Hamblett (1915-1993), and they went to live at Pangatotara, near Nelson (Colin and Ann were to have four children, William, Catherine, Victoria and Matthew).

Here he re-engaged with Woollaston, and with a group of young friends at Mapua they launched into ethical and intellectual debates, resolving to find a distinct ‘New Zealand art’ and break free from European traditions. Still struggling financially as a painter, McCahon worked in tobacco fields and orchards and as a builder’s labourer to support his growing family. Bicycling around the countryside looking for seasonal work he observed “big hills stood in front of the little hills which rose up distantly across the plain from the flat land: there was a landscape of splendour and order and peace.” In 1947 he had become a part of The Group, an influential collective of artists based in Christchurch (other members included regionalist co-conspirators Woollaston, Rita Angus and Doris Lusk) after being invited to exhibit in their 1940 and 1943 annual exhibitions. In 1948 the family moved to Christchurch where Colin worked as a gardener and began to exhibit regularly.

Starting out as a landscape painter, McCahon’s bold representations sought to capture the majesty and difficult essence of the southern land. His take on the terrain was new; McCahon’s landscapes weren’t romantic, but pared back, primitive, almost abstract, seeking an underlying structure. As a wedding present he had received a copy of geologist G.A. Cotton’s The Geomorphology of New Zealand (3rd ed. 1942), a scientific text examining landscape forms and processes and illustrated with sketches, diagrams and photographs. Cotton’s diagrams ignored built features, trees and objects irrelevant to his scientific themes; he was attempting to strip the landscape to its geological basis. These precise drawings would inform McCahon in his efforts to find the landscape’s spiritual basis.

At every turn, McCahon’s uncompromisingly individual works were underpinned by a deeply felt sense of place and a search to find symbols that might represent this sense. In Six Days in Nelson and Canterbury (1950) the six days of creation from Genesis are one reference in a montage of South Island landscapes. The landscapes are unpopulated, almost prehistoric (McCahon would describe the Otago landscape as ‘Egyptian’), the weather brooding. Each landscape has a primal simplicity: a still cut together with the next, like film, with a sacrificial blood red/brown waterfall splicing the sequence together. As if they are part of a road movie compiled of shots from one of McCahon’s bicycle journeys, a sense of movement between time and place is evoked. The locations are recognisably typical, but the contrasting lightness and darkness becomes a metaphor for spiritual dilemma. Aotearoa becomes a symbolic shadowland.

Six Days in Nelson and Canterbury, 1950 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

McCahon would return time and again to landscapes, his style intending to move the viewer from in front of, to within a painting, intending to, he says, “throw people into an involvement with the raw land, and also with raw paint … like spitting on the clay to open the blind man’s eyes”

The divine filter: sign-writing and God

In 1953 the McCahons moved to Auckland and lived in a small house set amongst kauri and native bush in French Bay, Titirangi. McCahon worked at the Auckland City Art Gallery, first as a cleaner, then as an attendant. By 1956, he was ‘Keeper’ (an English term for curator) and Deputy Director, organising exhibitions of contemporary and historical art, and writing catalogues. He painted and exhibited regularly, taught art classes at night and designed theatre sets. His position as custodian of collections at the gallery was a pivotal one that meant McCahon was actively engaged in the Auckland art world.

Colin McCahon photographed in the Auckland Art Gallery, 1961. Photograph by Bernie Hill. Collection of the E.H. McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tamaki.

From the late 1940’s Christianity exerted an increasingly prominent influence on McCahon’s paintings. Encouraged by James K Baxter (who found on McCahon’s canvas the “raw vitality and brutal simplification” of the whenua) he pursued a radical depiction of traditional subject matter. Baxter and McCahon had a complicated relationship (McCahon gestured towards Baxter in two well-known works painted nearly 30 years apart: A candle in a dark room (1947) – a Picasso-inspired symbolic portrait of Baxter – and Walk (1973), painted to farewell Baxter’s spirit after his death) but they shared a concern to depict universal, especially spiritual, themes, within a recognisably New Zealand landscape.

Angels and aeroplanes share the antipodean sky; crucifixions are set into the creased hills; power poles bear new meanings. When a series of biblical narrative paintings were published by his friend Charles Brasch in the literary magazine Landfall in December 1947 it brought McCahon to national attention for the first time. Most local critics were somewhat perplexed, unsure of how to place McCahon’s refiguring of the Christian canon within with the homely.

A visit to the United States in 1958 proved a watershed for McCahon. Nominally he was there to investigate how art museums were run as part of his gallery role, but he took every opportunity to take in art works he wanted to see. Inspired by the abstractions of Mondrian and the large-scale modernist works of Richard Diebenkorn, Jackson Pollock and Picasso – “pictures for people to walk past” – McCahon returned home to paint the now legendary Northland Panels (1958).

Northland Panels, 1958 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

Encouraged to think big, the large-scale statement of intent is bursting with the tension between McCahon’s re-acquaintance with the Aotearoa landscape and his recent engagement with the energy of the cosmopolitan centres. He laments the complacency with which the New Zealanders treat their iteration of the promised land: “a landscape with too few lovers”. The Tui’s blacks, blues and greens cry for Northland’s eroded and raw hills. This series was closely followed by Elias, (1959) a derivation of the crucifixion story. The two paintings signal a key development in the text-messaging trope he would make his own as a painter.

Elias will he come will he come to save him, 1959 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

McCahon had been interested in the shape of words and letters in art since his early childhood, when he recalls being fascinated by a sign-writer painting HAIRDRESSER AND TOBACCONIST on a shop window. Much later, McCahon would reflect, “I suppose my present glad acceptance of pop art is, in some ways, related to this experience.” Driven by a need to communicate directly, McCahon began using cartoon-like speech bubbles and signs and would later cover entire canvases with text. Australian art critic Peter Hill writes, “Even in terms of pure graphic design, he was decades ahead of his Madison Avenue contemporaries in the use of playful typography, cunning black and white reversals and juxtapositions of scale. But it is the content of the type that weeps.”

Hill describes McCahon as a “divine filter”, sucking in everything: influence, environment, the minutiae of existence. Quardle oddle ardle wardle doodle, on the canvas they bled – religion, advertising hoardings, linoleum, redemption, abstract expressionism, Maori symbolism, spirituality and verse, nicotine, guilt, alcohol, architecture, landscape. He turned painting into a graffiti grappling with universal truths and personal experience, an engagement with the edges of life: faith and doubt, choice and agency.

Working with word and image, McCahon’s pastiche was not painted with the irony of postmodernism, but with the urgency of divining substance.

In exploring the power of text to carry his message, McCahon formed key relationships with poets and writers. The most influential was with poet John Caselberg (1927- 2004), introduced to McCahon by Baxter in 1948. Over several decades Caselberg and McCahon had a close friendship and collaborated on a succession of works, including The Wake (1958) and The Second Gate Series (1962). The Wake is McCahon’s largest painting, on which awesome kauri trees stem from Caselberg’s eulogy to his recently-dead Great Dane, Thor. Caselberg would read the poem aloud to audiences in front of the work when it was originally exhibited, remembering Thor’s “Star-stabbed tui-throated, Open-artery-and-sea- engendered- Rainbow-swimming days”. The Second Gate Series is a powerful geometric abstract work where words drawn from the Old Testament fret about the threat of nuclear war.

Necessary Protection

When not sign-writing for God, worshipping his “lovely kauris” or painting metaphysical bombshelters, McCahon spent several years teaching and ran his own summer schools for fledgling painters. In 1960 the family moved to inner-city Auckland, to Grey Lynn. In 1964, after leaving the gallery, he taught at Auckland University’s Elam School of Fine Arts until 1970 when, at 51, he was finally able to paint full-time.

Through the 60s and 70s, now working from a beach studio at Muriwai, west of Auckland, he exhibited prolifically and continued to evolve his painting with inventiveness and radical simplicity; working towards a new level of abstraction. Standing before the canvas McCahon’s needs were binary. “I only need black and white to say what I have to say. It’s a matter of light and dark.” When abandoned by his brush, the paintings struggle – melancholic, hopeful – with the frisson between the poles of McCahon’s yin and yang: as stark or muted in relief as the hill is to the sky.

Muriwai, A Necessary Protection Landscape, 1972 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

The black and white abstractions of Muriwai, A Necessary Protection Landscape (1972) make possible manifold interpretations. The title suggests layers of significance for McCahon: protecting the gannets and terns roosting in the cliffs surrounding Muriwai beach; the possible threat of nuclear meltdown in the midst of cold war; the Maori tradition of the spirit’s journey along the black sand beach to its resting place; the cultural struggle for Maori affirmation in Aotearoa … even “protection” as a staunch against the stiff west coast south-west wind. The Large Jump (1973), a large symbolic work, suggests the gannets nesting on the cliff-tops at Muriwai, where fledglings are forced to confront the first daunting leap into flight from the nests that once protected them. But it gestures too, to transcending the frame, and to what McCahon called “my own particular God”. If anything, Jump is an endorsement of the life of the word and the word of life: its movement. McCahon wrote in 1971:

“I am not painting protest pictures. I am painting about what is still there and what I can see before the sky turns black with soot and the sea becomes a slowly heaving rubbish tip. I am painting what we have got now and will never get again. This is one shape or form, has been the subject of my painting for a very long time.”

Large Jump, 1973 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

I saw an angel in this land

McCahon lived a troubled life, its stains monumental on mural-sized canvas. This is particularly so of his later years when he struggled with alcoholism, illness, and a descent into dementia through Korsakov’s syndrome. The Stedelijk Museum’s Marja Bloem dubbed McCahon “the Van Gogh of Australasia”. If the life-is-the-art comparison is telling, so are comparisons with his centrist contemporary Rothko. Like Rothko’s, McCahon’s deep introspections leach into the abstract.

Yet McCahon was dubious about the importance of the artist’s life story to an understanding of the work. Burnt by encounters with news media, he avoided press interviews and firmly refused to be photographed, believing that the artist’s personality should remain subordinate to the power of his paintings to convey what he desired to communicate. “Why aren’t the paintings enough?” was always the question.

Yes, McCahon could be difficult (and he was fond of playing Hank Williams records), but one needs to be wary of taking the pained artist stereotype too far as explication. He wrote in 1974, regarding the idea of the soul’s journey represented in the jump motif, “it’s all serious … but funny too”. As cautious as he was about how he was represented, he was certainly not a recluse, nor did he conceive of art as existing in a mysterious vacuum to be divined by the viewer. McCahon the artist was also an engaged teacher, critic, curator, husband, father and, crucially, an articulate and devoted communicator. He wrote extensively in lectures, essays, interviews, catalogues and letters and he was a compelling advocate for his own work. His written cogency would put most gallery wall-text to shame:

“All the various gates I opened and shut at this time [Gate Series, 1961] were painted with reference to problems the painter Mondrian had struggled with in his work and I now confront too. How to make painting beat like, and with, a human heart. All his later paintings did this and I had to find out how. Some of mine did work and others were probably rejected transplants.”

And this, on how he, “rediscovered good old Lazarus”:

“Now this is one of the most beautiful and puzzling stories in the New Testament – like the Elias story this one takes you through several levels of feeling and being. It hit me, BANG! At where I was: questions and answers, faith so simple and beautiful and doubts still pushing to somewhere else. It really got me down with joy and pain … I believe but don’t believe. Let be, let be, let us see whether Elias will come to save him.“

“Most of my work has been aimed at relating man to man to this world, to an acceptance of the very beautiful and terrible mysteries that we are part of. I aim at very direct statement and ask for a simple and direct response. Any other way the message gets lost.”

Primarily he wanted his paintings to speak uncompromisingly for themselves (“Painting can be a potent way of talking”). When regarding the gravity of the aptly named Teaching Aids, he wrote in a letter:

“[they are to me] cold and distant […] I think them beautiful, [but] so very, very sad. Only I’m not a sad person. Maybe that’s why I do so many sad paintings? I’m aware of the sadness.”

No matter how baffling, his works live through their provocations and this drive to communicate inner conflicts. When he found that viewers were puzzled about the works’ meaning, McCahon struggled with how to clarify his message and this is how he bluntly explains his move to text in his paintings: “I will need words”. There is deep conviction in his mission: to stand in the place where he lives – his station, his turangawaewae – and to inspire tough thoughts about ethical questions, about joy and pain, about the land, and about God. The exhortation is for the viewer to make their own inquiries.

“My painting is almost entirely autobiographical – it tells you where I am at any given point in time, where I am living and the direction I am pointing in. In this present time it is very difficult to paint for other people – to paint beyond your own ends and point directions as painters once did. Once the painter was making signs and symbols for people to live by; now he makes things to hang on walls at exhibitions.”

Victory Over Death 2, 1970 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

McCahon lived on the edge of wider social and cultural acceptance, and was literally isolated down under, far removed from the nexus of the international art world. His eccentric use of Christian allegory was not readily understood in the conservative New Zealand society of the 1940s in which he first exhibited and the audience for contemporary art was virtually non-existent (particularly an audience prepared to open their wallets). The struggle for acceptance or wider understanding of his messages would recur through the rest of his career and his work could split opinions as decisively as the line of white paint cleaving the canvas in Waterfall (1964). “One day the balloon will go up”, McCahon used to say to his students. Sceptical New Zealand and Australian media, trained in the “my five year old could’ve done that” school of art criticism, were particularly vitriolic in response to one of his greatest works, Victory Over Death 2 (1970). This painting was selected by Hamish Keith and Peter McLeavey to be gifted by the New Zealand government to Australia to celebrate its bi-centenary in 1978. The occasion was cynically manipulated by Prime Minister Robert Muldoon – the New Zealand cabinet voted 5 to 1 not to buy the painting, but Muldoon preferred messing with the Australians (“Muldon’s Revenge” yelled one headline). The treatment created despair and paranoia for McCahon.

Despite continual puzzlement and sometimes derision in dairies and dining rooms, McCahon had been long championed by influential gallerists. The director of the Australian National Gallery, James Mollison, who had infamously purchased Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles for the ANG, was an admirer and had specifically requested one of McCahon’s paintings as the bicentenary gift. Throughout his career McCahon was supported by friends, collectors and informed critics. Dealers who had pioneered contemporary art in New Zealand – Peter McLeavey in Wellington and Barry Lett in Auckland – represented McCahon and exhibited his work frequently. His works were consistently sought for public and private collections and shown in multiple survey shows in New Zealand and Australia.

Yet, for an artist who aimed to create a public and “very direct statement” and who asked for a “simple and direct response” in return, the 1978 Victory Over Death controversy affected him as if he was in “slow burning hell”. “I’m not finished yet”, he said at the time, “just real buggered”. He despaired at the mass of imagery flooding television screens nightly and its impact on our collective image systems.

Debilitated by illness, he ceased painting altogether in the later years. Colin McCahon died in Auckland in 1987.

Colin McCahon, 1950 Photograph reproduced by permission of the Hocken Library, University of Otago.

A question of faith

With a retrospective exhibition entitled A Question of Faith, (after a work depicting the Lazarus story) at the Stedelijk in The Netherlands in late 2002, McCahon was recognised internationally. In a 2003 ArtForum feature on the exhibition critic Thomas Crow situated McCahon amongst the Parthenon of post-war modernists. “A major contemporary of Rothko, Newman, Pollock, Twombly, and Johns – an artist fully at their level of achievement – is in the midst of his first major touring retrospective. Most of you reading this will be in no position to see it. The artist is Colin McCahon, and, yes, he is that good.” Crow ends with the prophecy of a Lazarus-like revival: “That leads to the question: Might McCahon be better or more usefully understood outside of his own time? Beyond New Zealand and Australia, at any rate, he’s a new artist. Might it be the case that his day for Europe and for America has only just arrived?”

Crow’s provocation to consider McCahon in the context of international art history has been largely unheard, but even so, his, and the Stedelijk’s endorsement of McCahon is a validation of the edge theory: that the margins could offer a radical, independent, challenge to the authority of centre. An irony of the belated international endorsement is that McCahon’s works are so well represented in public and private collections in New Zealand and Australia that there is probably simply not enough stock to sell into an international public museum market.

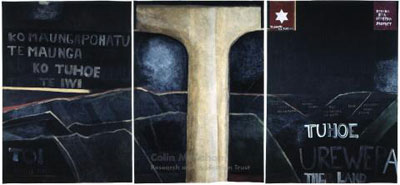

Nevertheless his local status as the cross-bearing luminary of New Zealand art is deeply entrenched, and even popularly recognised (the abduction of the Urewera Mural from a Department of Conservation visitor centre in 1997 by Tama Iti and colleagues ensured his continued notoriety). And any artist confronted with representing New Zealand’s landscape or its interior terrain must, at some point, cower beneath McCahon’s name, which looms in daunting block capital letters, like Stonehenge over a postmodernist.

Urewera Mural, 1975 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust. Crown Copyright, Department of Conservation

Critic Wystan Curnow, writing in 1977, compares McCahon to Moby-Dick writer Herman Melville, in that they both were provincials who created a “home-made art that is nevertheless utterly contemporary”. Three decades have excised the ‘nevertheless’; McCahon’s profound, personal New Zealand regionalism is the edge he offers us.

“If I got to Australia again I could be torn between there and here as I was in 1951. It does no good. And in the States I was mucked up by the open land around Salt Lake and out of Colorado. I don’t trust myself with new land. But here I know what I’m on about and don’t have to wonder where I belong and a problem is solved right away … I belong with the wild side of New Zealand. I’m too young yet to leave it.” McCahon, in a 1978 letter to Kees Hoss.

I AM

McCahon’s paintings communicate in a powerfully unique way, experimenting with abstractions, laden numerals, epic words and endemic shadows, to form his own brand of new-world modernism. For McCahon it was a wrested struggle for simplicity and power of concept (Here I give thanks to Mondrian). Nothing is more staunchly, ferociously, affirmative than the huge white on black, ‘I AM’ in Victory Over Death 2, (though its doubting reversal, ‘Am I?’ still lurks reflected in the shadows, painted black on black). There is nothing more despairing than the rectangular black void amongst the white text in his last painting, I considered all the acts of oppression (1980). Walking on the wild side of New Zealand, McCahon split the sky and found a way of seeing:

“I saw something logical, orderly and beautiful belonging to the land and not yet its people. Not yet understood or communicated, not even really yet invented. My work has largely been to communicate this vision and to invent the way to see it.”

References

Web Links:

[Accessed May 2008]

Colin McCahon Image Library and Database: http://www.mccahon.co.nz/Home.htm

Gordon Brown entry on McCahon in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography: http://www.dnzb.govt.nz/dnzb/

Spreading the word: Colin McCahon: Thomas Crow talks with Maria Bloem – curator Maria Bloem discusses the Colin McCahon paintings exhibited in A Question of Faith – Interview http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_1_42/ai_108691803/

Colin McCahon: by Jason Smith, Curator of Contemporary Art, National Gallery of Victoria http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/mccahon/essay.html

Selected written works on McCahon:

Colin McCahon A Survey Exhibition. Catalogue with personal commentary from McCahon, for the survey exhibition organised by the Auckland City Art Gallery, 1972.

Colin McCahon, Gates and Journeys, Catalogue for the survey exhibition organised by the Auckland city Art Gallery, with biography, exhibition history and essay by Gordon Brown, 1984. The quotes from McCahon in this piece were sourced from the Gates and Journeys catalogue.

Colin McCahon, Necessary Protection. Catalogue to accompany the exhibition of McCahon’s various series from 1971 to 1976, introduced by Wystan Curnow. Published by Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 1977.

Bennie, Angela, “A Titanic Struggle With Faith”. The Dominion Post, 21 November 2003, p. B10.

Brown, Gordon H. Colin McCahon: Artist (New Edition). Auckland: Reed Publishing, 1984; 1993.

Bloem, Marja and Martin Browne, Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith. Catalogue to accompany the Stedelijk exhibition. Co-published by Craig Potton Publishing and the Stedelijk Museum of Art in the Netherlands, 2002 http://www.craigpotton.co.nz/products/published/books/ The quotes from Rudi Fuchs are taken from here.

Crow, Thomas. “Spreading the Word: Colin McCahon: Thomas Crow talks with Marja Bloem.” Artforum. September 2003.

Curnow, Wystan, I Will Need Words: Colin McCahon’s Word and Number Paintings, National Art Gallery, 1984

Rosalie Gascoigne – Colin McCahon: Sense of Place, Ivan Dougherty Gallery, Sydney; Louise Pether curator, 1990.

Hill, Peter. “A Filter of Faith.” Rev. of A Question of Faith. Sydney Morning Herald, 15 November 2003.

Simmons, Laurence. The images always Has The Last Word: On Contemporary New Zealand Painting and Photography, 2002

Wood, Agnes, Colin McCahon: the Man and the Teacher. Auckland: David Ling, 1997.

Documentary:

Colin McCahon: I AM, Director: Paul Swadel, Producer: Robin Scholes, Associate Producer: Rachel Gardner, Editor: Jonathan Brough, Director of Photography: Leon Narbey.Sponsored by SweeneyVesty. http://tvnz.co.nz/

Colin McCahon ‘I Am’ DVD cover, 2006

Ideas for Further Reading:

Simpson, Peter. Answering Hark, McCahon/Caselberg: Painter/Poet. Nelson, NZ: Reed Publishing, 2001.

Shepard, Deborah, ed. Between the Lines: Partners in Art. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2005.