Team McLaren has been the most successful team in world motorsport since it appeared in 1966. McLaren cars and drivers have taken the chequered flag at Grand Prix races 182 times, won 12 Formula One World Championship titles (more than any other team in the history of the sport), dominated CamAm events (56 wins between 1967 and 1972) and taken three Indianapolis 500 races. The man who started it all, Aucklander, Bruce McLaren, was a brilliant driver, with vision that extended far beyond the driver’s seat. He became the engineer, the inventor, the constructor, the tester. Bruce McLaren took the essence of the New Zealand Edge and transformed it into arguably the greatest motor racing team in history.

In the 1960s and 70s it was New Zealanders Denny Hulme and Bruce McLaren himself who drove the McLaren cars to victory; in the 1980s it was Alain Prost; in the 1990s the great Ayrton Senna; and in 1998 and 1999 it was Mika Hakkinen who took the Drivers Championship titles. The best and fastest drivers have always been attracted to McLaren – Hunt, Lauda, Fittipaldi, Revson and Mass included. The cars, then the reputation, grew from a combination of talents, Bruce McLaren’s talents, which became very evident early in his career.

Since McLaren cars first appeared on race tracks in 1966, they have taken eleven Formula One Drivers’ World Championship titles and eight Formula One Constructors’ World Championship titles; between 1988 and 1991 the McLaren team won four Constructors titles consecutively, the only team ever to do so. To date McLarens have raced in 770 Grand Prix and have scored 182 wins. This places the team second behind Ferrari. However, Ferrari started racing 16 years before McLaren cars.

McLaren racers have not only achieved in Formula One. There were victories in the Indianapolis; 500 in 1972, 74 and 76; and the McLarens driven by Bruce and Denny Hulme totally dominated the Can Am series, winning five consecutive Constructors’ Championships between 1967 and 71 (this was the “Bruce ‘n Denny Show”).

Bruce McLaren’s year of brilliance 1969. Driving his Formula One car, he was third in the World Drivers’ Championship and drove his own M8B to his second Can Am championship (pictured). Permission Patricia Kerr, Champions of Speed

From McLaren – A Racing History, Geoffrey Williams writes:

“Just as Jackie Stewart came to personify the increasing professionalism, commercialism and safety consciousness of Grand Prix racing in the 1970s and similarly so with Ayrton Senna as the dedicated professional of the 1990s, Bruce McLaren typified the happy, often comradely spirit of earlier times. The most universally liked driver of his era, Bruce’s background suggested he may have something out of the ordinary to offer the sport.”

McLaren – New Zealander

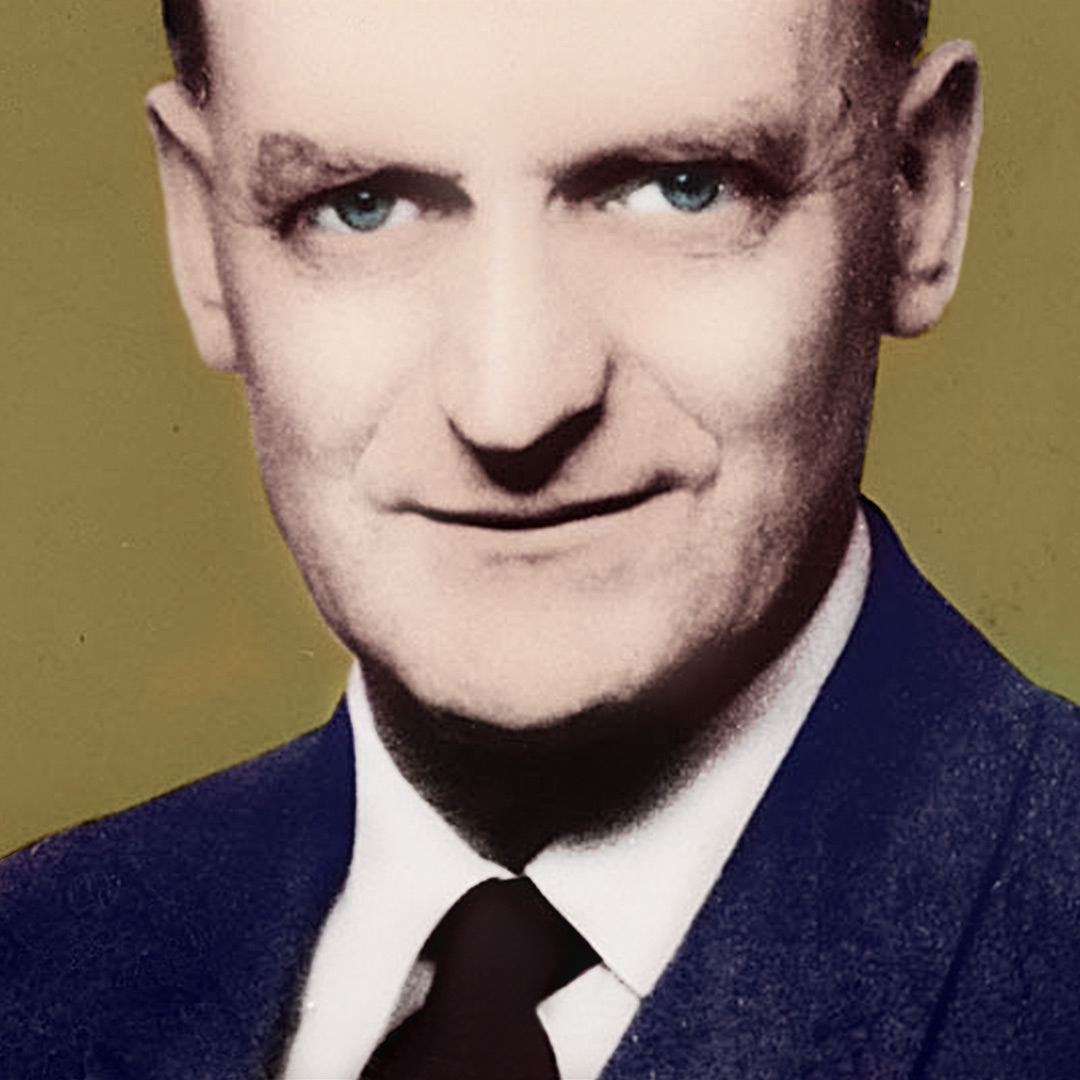

Born on August 30, 1937, in Auckland, New Zealand, Bruce McLaren may have been destined for a life revolving around cars and engines, but there were also massive hurdles to overcome.

His parents, Ruth and Les, owned the Shell service station and workshop on Remuera Road, Auckland. As a child Bruce spent many hours in and around the workshop. The sound of engines being tested and the smell of grease and petrol would have been constantly invading his senses. His love of speed, as family legend recalls, was evident early on when Bruce, on his trike, would terrorise the working mechanics.

At the age of nine, tragedy struck. Bruce developed Perthes Disease, a rare condition caused by insufficient lubrication of the hip joint. For the next two years he was confined to the Wilson Home for Crippled Children, harnessed into a contraption called a Bradshaw Frame. Through the ordeal he kept his spirits up, talking to his father about the cars that were coming into the workshop; accepting and looking beyond his predicament. His positive nature and optimism would be a great asset to him in later life. His recovery took two years and left him with a permanent limp.

With his health restored, McLaren’s full concentration was taken up with cars and then motor racing. His father was a motor racing enthusiast, competing in local hill climbs and time trials. Through genetics and learned behaviour, McLaren caught the car bug. Together father and son restored an Austin 7 Ulster. McLaren says, in his own words:

“With a truck full of boxes of spare parts and towing the Austin Ulster arriving at 8 Upland Road, my motor racing career had started. How Mum put up with Dad and me with her kitchen table covered in bits and pieces of the engine during meals I will never know. She used to say “If I gave them dry bread and water they wouldn’t have noticed.”

It was in his parents’ classic Kiwi quarter acre backyard – figure 8s around the fruit trees – that McLaren learned to drive. Later – at local hill climbs, gymkhanas and sprint meetings – he learned the basics of racing. Says Richard Becht in the book Champions of Speed:

“That was the early secret of Bruce McLaren’s success on a world scale. He learned to drive – and wipe out – as early as possible. He had his own car. He as good as had his own garage, not to mention he was engulfed in motor racing with his father still competing.”

McLaren – Driver

Another major factor in McLaren’s success, as with Chris Amon and Denny Hulme, was the New Zealand International Grand Prix. Existing between 1954 and 1969, it was popular on the international circuit, allowing European and American drivers to escape the northern winter. As Sterling Moss recalled, it let the big name teams get rid of their old hardware.

“You could leave your old cars in New Zealand for the locals to buy and then we could get new ones for the new Grand Prix season. We were able to get rid of the crap at the end of the season. But that was a help to the drivers in New Zealand to have our cars. Absolutely.”

McLaren graduated from his Ulster to a Ford 10 Special, to an Austin Healy, then a Cooper Climax Sports. With the improved cars came improved driver performance. By 1957, his wins on the domestic scene were enough for him to qualify for that year’s Grand Prix. The 1957 event is remembered as the race where British driver Ken Wharton crashed and later died; and where McLaren first came to the attention of Australian legend Jack Brabham.

New Zealand Grand Prix Ardmore January 10 1959. Bruce McLaren in the paddock with the Cooper Team car

New Zealand Grand Prix Ardmore January 10 1959. Bruce McLaren racing in the Cooper Team car. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of these images.

While not winning the Grand Prix, McLaren did show enough promise to be selected for the New Zealand International Grand Prix organisation’s ‘Driver in Europe’ scheme; an initiative established to give local drivers year-round exposure to the best in the world. McLaren was the inaugural recipient, Chris Amon was another.

The young Bruce McLaren in his Cooper days at the French Grand Prix c. 1960 where he placed 3rd. Permission Patricia Kerr, Champions of Speed

Brabham was driving for the Cooper team and he persuaded them to give McLaren a spot. He was promised a workshop, a wage and a new Formula Two Cooper on arrival in England. His “new car” turned out to be a mass of pipes lying on the Cooper factory floor. He had to build it himself, from scratch; a skill not generally required of drivers. Those years in the Auckland service station workshop were immediately useful.

Bruce McLaren, an expert at cornering (one ski only owing to his earlier hip problem), takes a tight turn with a swish of spray on a single ski at Auckland’s Orakei Basin. Waterskiing was one of Bruce’s favourite sports; here he skis before going off to test his Cooper 2.5 in preparation for New Zealand Grand Prix practice day at Pukekohe. 8 January 1964. Permission News Media, Auckland

What made McLaren a brilliant driver? A natural gift, yes, but also the New Zealand environment. Years of tricky hill climbs one weekend, than a flat circuit the next; having to mechanically improvise with old cars, learning how they worked and making them faster. His experience brought rapid results in Europe.

McLaren’s performance in the 1958 German Grand Prix at Nurburgring confirmed his promising potential. This 14 mile, 170 corner track intimidated the most experienced drivers. The race combined both Formula One and Two; McLaren took the Formula Two chequered flag, with only four Formula One cars ahead of him. Yet he had initially only been the reserve list for the race.

Charles Cooper promoted him to Formula One and the next year he won the American Grand Prix at the age of 22, the youngest ever driver to earn this honour.

By 1960, Coopers were the dream team. Jack Brabham, the seasoned campaigner, finished the year as number 1 driver in the world, and Bruce McLaren, the affable, laid-back Kiwi sensation, stood beside him at number 2; Sterling Moss, also with the Cooper team, came third. McLaren won the Argentinian Grand Prix that year. He had risen from obscurity to stardom in less than two seasons.

McLaren would remain in the top 10 drivers in the world for the next 10 years. His popularity never dimmed, nor his enthusiasm. The only thing that changed was his ever-increasing influence over the world of motor racing.

McLaren – Engineer

From Champions of Speed by Richard Becht:

“It was never just the racing that McLaren longed for. It was the complete picture. There was the fascination and obsession with the cars themselves, the respect he had for them, the satisfaction he derived from working on them, and the absolutely thorough knowledge and understanding – the mechanical sympathy – he had for racing cars, or any car.”

Bruce McLaren’s passion for cars didn’t stop at the racetrack. In his early days in England he favoured Jaguars. Here he lovingly cares for his brand new E-Type outside his Surbiton flat in 1961. Permission Phil Kerr, Champions of Speed

By 1963, McLaren had become dissatisfied with the Cooper team’s development work. He was caught between loyalty to Charles Cooper, who had given him his start, and his own ambitions. Rather than seek out another team, he decided to follow Jack Brabham’s lead (who had formed his own team in 1962) and go out on his own.

But between 1963 and 1966, McLaren continued to race for Cooper, and maintain his consistent top ten world placing, while at the same time designing his own car.

At first the experiment proved frustrating. McLaren’s first Formula One chassis was excellent, but he was not able to match the body with an adequate engine. The first McLaren cars used under-powered Italian Serenissima engines, and in 1966, the first year a McLaren car raced, they were only able to achieve a 6th in the British Grand Prix.

In the meantime, McLaren was involved with the Ford GT programme, and also built the remarkable “whoosh-bonk” M3 single-seater (“whoosh”, you could take the suspension from the sports car, “bonk”, because you knock together a spaceframe chassis around it, and you’ve got a car). The M3 was the MGM camera car for the film Grand Prix.

Winning Combinations

The McLaren racing programme accelerated with the addition of two factors. McLaren designer, Robin Herd, introduced the Ford Cosworth engine to the car; and McLaren enlisted the driving services of fellow New Zealander, World Champion Denny Hulme (1967, in a Brabham). Denny Hulme has been described as in many ways the archetypal New Zealander: quietly assertive and hard working.

Chris Amon was the third man. In 1963, Amon had been the youngest ever driver in Formula One and he had become one of Enzo Ferrari’s personal favourites. In 1964, he accepted McLaren’s offer to test cars for his fledging team. McLaren and Amon teamed up again in 1966 driving a Ford GT40 in the Le Mans 24 hour race. The New Zealanders won.

The McLaren/Hulme/Amon combination was to dominate world motor racing in the late 1960s. The three Kiwis had many moments of glory on the American and European race tracks, the most symbolic being McLaren’s win at the 1968 Belgium Grand Prix in the Ford-Cosworth powered M7A that bore his name.

Doug Nye’s story of that race, records that Spa-Francorchamps’ Circuit National “is perhaps the most classical Grand Prix venue of them all. Spa takes no prisoners – a 270 kph tremor. To win there, is to climb motor racing Everest. What a place, then, for a team to gain its first championship Grand Prix victory.”

McLaren had won, but didn’t know it. Nye quotes McLaren:

“It’s about the nicest thing I’ve ever been told. Jackie [Stewart] had stopped at the pits for fuel starting the last lap and I hadn’t seen him as he went by. I had won without realising it…”

One of he most memorable wins was the Daily Express race at Silverstone in 1968 when McLaren and Hulme came in first and second in their McLaren cars and Amon came third in his Ferrari.

Bruce McLaren at the 1967 United States Grand Prix. Permission Patricia Kerr, Champions of Speed

McLarens were to dominate motor racing for the next two years, and not just Formula One. McLaren was Can Am Champion in 1967 and 1969 in his own cars, Denny in 1968 and 1970. The McLaren Trust website recalls this era:

“In these years cars of almost any innovation and imaginative design with supercharged 7-8 litre engines in a chassis with ultra-wide wheels and high wings, were allowed to run on the race tracks of North America. This was a period of beautifully designed cars driven by legendary drivers from all over the world. They came all for fun, glory and the largest purse in prize money in the world.”

The US and Canada race series was nicknamed the ‘Bruce and Denny show’. The two men, one easy-going and likeable, the other solid but gruff, are described by Geoffrey Williams in McLaren – A Racing History:

“…perhaps the most harmonious driving partnership of all time; that the Can Am series became known as the ‘Bruce and Denny show’ was not solely due to their hegemony, but also reflected their working relationship. In a sport, which is dominated by individuals’ egos, this was indeed a rare combination.”

The McLaren team in the late 1960s was not created by a revolution. Its success was not from a flash of inspiration,or a momentary rush of brilliance. It came from McLaren’s engineering genius and pure enthusiasm for cars, and Hulme’s love of and excellence in driving. The team, and the men, were as big in the sport as anyone had ever been.

Death At Goodwood

The pair were at the height of their powers when disaster struck.

While testing his latest Can Am car at the Goodwood track in England, the rear-hinged bodywork suddenly flipped open and sent the car spinning into a nearby concrete flag station platform. Bruce McLaren was killed instantly.

It was 12.22pm, June 2, 1970. He was 32. His mother Ruth, in bed in Auckland, woke suddenly at the very moment of the crash. She sensed what had happened.

A tragedy for the family, tragedy for motor racing, tragedy for New Zealand. In a country where tinkering with an old car on a Saturday afternoon is a national past time, McLaren had become the most famous, and most successful, ‘tinkerer’ of them all. He had shown the exotic and glamorous world of international racing could be brought closer to the garages of suburban New Zealand through determination, innovative thinking, belief and a sheer love of what you are doing.

Denny Hulme in the pits at the 1970 German Grand Prix

Chris Amon at the Formula One California, 1971. Permission Patricia Kerr, Champions of Speed

Pete Lyons records, in the Motor Sports Hall of Fame ,that Bruce McLaren was “universally well liked and remarkably self effacing. He never claimed to be the world’s fastest driver and often smilingly discounted his own engineering ability. “Make it simple enough so even I can understand it,” he’d tell his team. But his own work at the drawing board and in the cockpit resulted in racing machines that vanquished all comers.”

The success of McLaren, Hulme and Amon in taking on the world, the big teams with the big money, was an incredible feat. These achievements did as much for New Zealand’s international fame and for and New Zealand motor racing in the 1960s and 70s, as Team New Zealand has done for New Zealand and sailing since the mid 1990s.

The modern company of McLaren International has evolved into a multi-billion dollar enterprise dedicated to winning in the most watched and most expensive of all sports, Formula One, and to producing limited edition high performance road vehicles. McLaren International is located in Woking, England, with expertise supplied by a 325 strong team of designers, engineers and skilled staff, complemented by advanced computer-aided design and manufacturing facilities.

By continuing to bear the founder’s name, they acknowledge the New Zealand inspiration for the company.

Bruce McLaren made the ordinary become extraordinary. He took the basics of driving, construction and engineering, and perfected them. As Allan Dick tributes McLaren in Driver Magazine:

“When you reach the level of driving needed to drive a Formula One car, every driver possesses skill that mere mortals will never begin to understand. Bruce McLaren had the added advantage of a keen mechanical and engineering mind that was married to a typical Kiwi do-it-yourself attitude.”

Bruce McLaren’s record:

101 Grand Prix starts

4 wins

196.5 points scored

Formula One Championship placings:

1958 Cooper ( German, Moroccan GP only),

0 points

1959 Cooper, 6th

1960 Cooper, 2nd

1961 Cooper, 7th

1962 Cooper, 3rd

1963 Cooper, 6th

1964 Cooper, 7th

1965 Cooper, 8th

1966 McLaren, 14th

1967 Eagle (French, British, German GP only)

1967 McLaren, 14th

1968 McLaren, 5th

1969 McLaren, 3rd

1970 McLaren, 14th (South African, Spanish, Monaco GP only)

Winner Le Mans 24 hours, 1966

Winner Sebring 12 hours, 1967

Can Am Series Champion, 1967, 1969

Team McLaren’s record:

F1 Constructors Championships

1998, 1991, 1990, 1989, 1988, 1985, 1984, 1974

Drivers’ Championship (McLaren drivers)

1999, 1998, 1990, 1989, 1988, 1987, 1985, 1984, 1983, 1975, 1973

Ayrton Senna 35 wins for McLaren, 3 Championships

Alain Prost 30 wins, 3 Championships

Mika Hakkinen 14 wins, 2 Championships

James Hunt 9 wins, 1 Championship

Nikki Lauda 8 wins, 1 Championship

Denny Hulme 8 wins

Emerson Fittipaldi 5 wins, 1 Championship

David Coulthard 5 wins

John Watson 4 wins

Peter Revson 2 wins

Bruce McLaren 1 win

Jochen Mass 1 win

While Ferrari has been the most successful team with 129 wins to date (April 2000), it has been racing for 17 years more than McLaren, has been in 128 more Grand Prix and has only achieved six more Grand Prix wins.

McLaren’s win rate is 123/493 (one win for every four races), Ferrari’s is 129/621 (one win for every five races).

Championships have been won with the aid of Ford, TAG Porsche, Honda and Mercedes engines.

McLaren GTR won Le Mans in 1995

Sources

Web references:

McLaren Heritage:

http://www.mclaren.com/formula1/heritage/

For the Bruce McLaren Trust site:

http://www.motorsport.co.nz/mclaren/index.htm

[accessed April 2000]

For the official Team McLaren web magazine:

http://www.mclaren.co.uk/

[accessed April 2000]

For a site covering McLaren’s times and placings:

http://www.albedo.net/~marko/main/drivers/mclrn.htm

[accessed April 2000]

For Doug Nye’s story of Bruce’s 1968 Belgian GP win:

http://www.mclaren.co.uk/mclaren/features/blood.html

[accessed April 2000]

Motorsports Hall of Fame

http://www.mshf.com/hof/mclarenb.htm

[accessed April 2000]

Books:

Jones, Bruce. ed (1st published 1995), The Ultimate Encyclopaedia of Formula One, Carlton Books, UK

Becht, Richard. (1993), Champions of Speed, Hodder Moa Beckett, New Zealand

Williams, Geoffrey. (1991), McLaren – A Racing History, The Crowood Press, UK

Articles:

Pearce, Bob (1999) “Daimler to spend $1b on Stake in McLaren”, New Zealand Herald, July 14

Potter, Tony. (1995) “Legend of the racetrack”, Sunday Star Times, November 26

Dick, Allan. (1995) “Bruce McLaren”, Driver Magazine, June

I loved to read this great insight to the early days of the great Bruce McLaren,a wonderful driver, mechanic, engineer but most importantly a great man, my only critic concerns the mis-spelling of Stirling Moss, not Steling, and the fact that Moss was not a works Cooper driver alongside Jack Brabham and Bruce, but his Cooper was owned and entered by the private team of Rob Walker.

John, May 2014 A great team, the three "Kiwi Boys"' To my mind Bruce's achievements were greater than Hillary's. Perhaps one day he will be recognized by New Zealand as a whole.

You are amazing Bruce mclaren

September 2001 "I discovered this site by accident. But what a great job you have done! I enjoyed the Heroes section especially about Richard Pearse and Bruce McLaren. I would like to see something done on Bill Hamilton." Tom Emergency Services Tom Price, Australia

I was, in the last couple of days, moved to think of Bruce McLaren, and your website dedicated to him was very nicely done. Thanks I learned some. Though I first saw Bruce drive in the late '50s at Silverstone, I remember best watching the Bruce & Denny show at Bridgehampton USA. I went to the British GP in 1970 and it was very sad to see the orange cars without Bruce. Keith Crossley. IT Webster, New York, USA