‘I believe the greatest failing of all is to be frightened.’ Katherine Mansfield, letter to John Middleton Murry, 18 October 1920

Katherine Mansfield revolutionised the 20th Century English short story. Her best work shakes itself free of plots and endings and gives the story, for the first time, the expansiveness of the interior life, the poetry of feeling, the blurred edges of personality. She is taught worldwide because of her historical importance but also because her prose offers lessons in entering ordinary lives that are still vivid and strong. And her fiction retains its relevance through its open-endedness—its ability to raise discomforting questions about identity, belonging and desire.

Katherine Mansfield’s brief life was also a lesson in casting off convention. Famously, Mansfield remarked ‘risk, risk everything’. In the words of one of her biographers, ‘It was largely through her adventurous spirit, her eagerness to grasp at experience and to succeed in her work, that she became ensnared in disaster . . . If she was never a saint, she was certainly a martyr, and a heroine in her recklessness, her dedication and her courage.’

The Great Ghost

Virginia Woolf once said that Katherine Mansfield had produced ‘the only writing I have ever been jealous of.’ Woolf also, jealously, wrote, ‘ . . . the more she is praised, the more I am convinced she is bad.’ D.H. Lawrence, with whom Mansfield had a fraught friendship, visited Wellington, her birthplace, and was moved to send Mansfield a postcard bearing a single Italian word, ‘Ricordi’ (‘memories’). It was a small and cryptic gesture of reconciliation; they’d fallen out badly and in his previous letter he had said ‘You are a loathsome reptile—I hope you will die.’ T.S. Eliot found her ‘a fascinating personality’ but also ‘a thick-skinned toady’ and ‘a dangerous woman’. And, if we want to add one more voice to this roll-call of mixed, self-clashing responses: the Irish writer Frank O’Connor, in his classic study of the short story, The Lonely Voice, called Mansfield ‘the brassy little shopgirl of literature who made herself into a great writer.’

As New Zealanders we tend to think we have invented the ambivalence that surrounds our most famous writer. Our often grudging admiration perhaps has the cast of a distinctively local attitude to high artistic achievement. Yet Katherine Mansfield was always divisive, wherever she was received. The impression she left on those who knew her was strong and ambiguous. She affects her readers in a similar way.

After Mansfield died, Virginia Woolf often dreamed at night of her great rival. The dreams gave her a Mansfield who was vividly, shockingly alive, so that the ‘emotion’ of the dream encounter remained with Woolf for the next day. Hermione Lee, Woolf’s biographer, writes that ‘Katherine haunted her as we are haunted by people we have loved, but with whom we have not completed our conversation, with whom we have unfinished business.’ It is a formulation that captures wonderfully the current position of Mansfield. She is a key figure in the development of the short story and yet she remains somehow on the margins of literary history. She is also the great ghost of New Zealand cultural life, felt but not quite grasped.

A New Zealand of the Mind

Unfinished business lies at the heart of the Mansfield life story, not least because she died young—in 1923 at the age of thirty four, the author of just three books of short stories (a fourth and fifth would appear after her death). Her own feeling, as she was dying of tuberculosis, was that she had only just started as a writer. Two weeks before she died, she expressed, with characteristic restlessness, her dissatisfaction and her ambition: ‘I want much more material; I am tired of my little stories like birds bred in cages.’ Yet there are other aspects of the life that also bear the stamp of incompletion.

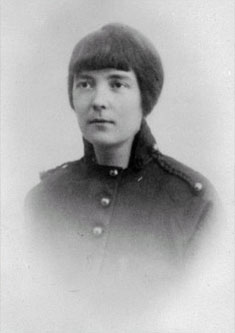

Katherine Mansfield with her sister Jeanne and her brother Leslie. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

Mansfield left for London in 1908 aged 20, never to return to New Zealand. In the context of a long and arduous sea journey – six or seven weeks—this might not appear significant. And yet by the time Mansfield’s father, who’d been born in Australia, came to write his memoirs, he could boast that he’d made the trip ‘back’ to Mother England twenty-four times. Later in her life, of course, Mansfield was frequently incapacitated by illness. Even allowing for this, it is obvious that she saw no point in a return voyage to her birthplace—and that has had an effect on how we, as New Zealanders, see her. Though D.H. Lawrence believed the most important fact about her was that she was a colonial, Mansfield can seem to us, at first glance, ‘too English’; her associations with the Bloomsbury set, her marriage to an English man-of-letters, keep her rather at a distance from our concerns. Irrationally, we feel abandoned.

And yet her masterpieces—the long stories ‘At the Bay’ and ‘Prelude’—are lovingly detailed recreations of a New Zealand childhood, reports from the fringe—the edge of the world as she felt it to be. She wrote as if she’d stayed. Of course these luminous re-imaginings are lit with the affection and nostalgia of the expatriate. They would not exist without their author’s estrangement from the scenes and places and people she describes. They are set in a New Zealand of the mind, composed at the edge of Mansfield’s memory.

‘At the Bay’ and ‘Prelude’ are Mansfield’s most innovative and widely-read works and as such they are often the only point of contact an international readership has with this obscure country at the bottom of the world. And so our sense of abandonment is corrected slightly by a feeling of pride.

Mansfield’s relationship with her country of birth was, like most of her relationships, marked by extremes. In the beginning, as a precocious, literary schoolgirl, she despaired of her uncouth colonial home where ‘people don’t even know their alphabet’. As a mature writer she found in that ‘hopeless’ material a way of pushing the boundaries of the form—in the words of her biographer, Antony Alpers, a means of ‘revolutionising the English short story’.

Where did that revolution start?

Wellington in the 1880s, showing the Beauchamp house. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

Imaginative Truths

Mansfield was born Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp in Wellington in 1888. Her father, Harold Beauchamp, was a successful businessman who, by the time of Mansfield’s adolescence, had become a director of the Bank of New Zealand.

Mansfield’s mother, Annie Dyer, has been described as ‘delicate and aloof’, with a gift for unthinking pronouncements. Her first words to her artistic daughter, on returning from nine months in England, were, ‘Well, Kathleen, I see that you are as fat as ever.’ Mansfield was to draw on her mother for the character of the reclining, perpetually disappointed Burnell mother in ‘Prelude’, pregnant again and victimised by disturbing dreams of a bird swelling into a baby ‘with a big naked head and a gaping bird-mouth, opening and shutting.’

Mansfield was sent off to London in 1903 to attend Queen’s College, a school for the liberal education of women. Three years later, she was reluctantly back in Wellington, rebellious and full of ‘ideas’. Writing to a school friend at the age of sixteen, Mansfield sets out the programme:

‘I’m so keen upon all women having a definite future — are not you? The idea of sitting and waiting for a husband is absolutely revolting and it really is the attitude of a great many girls . . . It rather made me smile to read of your wishing you could create your fate — O how many times I have felt just the same. I just long for power over circumstances.’

The longing was expressed in such acts as wearing brown to match the colour of her beloved cello; and punching her best friend if that friend talked to another girl. One of her headmistresses called Kathleen ‘imaginative to the point of untruth’.

The headmistress was on to something. Of course what Mansfield was looking for were imaginative truths. She had begun to write stories and poems. Mansfield’s juvenilia are no more or less mawkish than the youthful work of any writer; what is occasionally noteworthy is the degree to which the future figure of the artist can be heard sounding her characteristic notes. Here is an extract from an abandoned novel:

“Live this life, Juliet. Did Chopin fear to satisfy the cravings of his nature, his natural desires? No, that is how he is so great. Why do you push away just that which you need —because of convention? Why do you dwarf your nature, spoil your life? . . . You are blind, and far worse, you are deaf to all that is worth living for.”

This is ‘vintage Mansfield’ in many ways—the frenzied exhortation to live, which is central to all Mansfield’s writing; the opposition of convention and nature; the terror of falseness; the elevation of the great artist as the model for living and, by extension; art as a means of being ‘real’; the notion that destiny is a function of desiring—to want something strongly enough is to legitimise the means of getting it. Here it is all baldly stated. In her most persuasive work, Mansfield would find a way of pressing the threads of such a credo into the weave of her fiction.

The Bogey of Love

In 1908, Mansfield finally persuaded her father to let her go back to London, ostensibly to continue with her music studies. In yet another self-addressed journal manifesto, she wrote of the need to get rid of ‘the doctrine that love is the only thing in the world’: ‘We must get rid of that bogey—and then, then comes the opportunity of happiness and freedom.’ Exercising her gift for contrary behaviour, Mansfield promptly fell in love with Garnet Trowell, a young violinist. When the affair collapsed, she impulsively married G.C. Bowden, a singing teacher, leaving him the day after the wedding. She resumed her relationship with Garnet, became pregnant, and eventually had a stillborn child.

Harold Beauchamp, 1909. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

By this time, through her mother’s influence, Mansfield was staying in Germany at a Bavarian health spa. Her mother had arrived in London to ‘sort out’ the business of Mansfield’s close friendship with an old Queen’s College friend, Ida Baker. Mother was wrong—there was nothing ‘unwholesome’ in the relationship, at least not along the lines she imagined. Ida Baker, variously nicknamed Jones, the Albatross, the Cornish Pasty, the Faithful One, became Mansfield’s lifelong helpmate, nursemaid and whipping post. Her devotion was unwavering in the face of some extraordinary insults and unkindnesses. Mansfield found Ida’s self-sacrifice galling and irritating; she also understood the large debt she owed her and was constantly admonishing herself for these sentiments. In a letter of 1922, Mansfield writes to Ida: ‘I am simply unworthy of friendship . . . I take advantage of you—demand perfection of you—crush you . . .’ Eight years earlier in a journal entry, thinking about Ida, she wonders whether she has ‘ruined her happy life?’

The waters did not ‘cure’ her of Ida Baker but Mansfield discovered in Germany a subject that could match her satiric talent. She began to publish sharply comic stories in a small weekly arts paper, the New Age, and in 1919 her first book came out.

In a German Pension showed Mansfield on the offensive. Stories such as ‘Germans at Meat’, ‘The Baron’ and ‘The Modern Soul’ gleefully skewer the pomposities and self-deceptions of the spa-going German middle class. The Germans are fanatically humourless, routinely condescending, and always eating. The narrator observes of one Frau who is affecting to be shocked : ‘If it had not been for her fork I think she would have crossed herself.’ Seeking purity and good health, they always give themselves away through unconsciously polluting acts: ‘Prompted by the thought, he wiped his neck and face with his dinner napkin and carefully cleaned his ears.’

The narrator, the stand-in for Mansfield, is an attractively dry, English-speaking outsider who has simply to turn up at mealtime to be presented with another amusingly offensive outburst. At one point she is offered cherries by an absurd music professor, who tells her: ‘There is nothing like cherries for producing free saliva after trombone playing, especially after Grieg’s ‘Ich Liebe Dich’’

The book was well received and the talent it announced—bracingly witty, clear-eyed, fierce—brought Mansfield promisingly into London literary circle for the first time.

Learning to be Brutal

In 1912 she met and quickly married John Middleton Murry, an Oxford undergraduate and already the founding editor of a small literary journal with a modernist agenda, Rhythm. Murry wanted to champion writing and art that was un-English, experimental, full of ‘guts and bloodiness’. The journal’s slogan, taken from the Irish playwright J.M. Synge, set out the terms of engagement, ‘Before art can be human again it must learn to be brutal.’

Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

His new wife, whom he called ‘Tig’ (they were now ‘the two tigers’ and he was ‘Wig’), obliged with a suite of New Zealand stories: ‘The Woman at the Store’. ‘Ole Underwood’ and ‘Mollie’. For Vincent O’Sullivan, the noted Mansfield scholar and writer, these often neglected pieces are essential to the oeuvre, being ‘the first New Zealand stories to thread human behaviour with the brooding grimness of landscape.’

‘The Woman at the Store’, a kind of colonial murder ballad in which the social isolation of rural life breeds despair and violence, contributed this much-quoted sentence to the dictionary of definitions a country keeps of itself:

‘There is no twilight in our New Zealand days, but a curious half-hour when everything appears grotesque—it frightens—as though the savage spirit of the country walked abroad and sneered at what it saw.’

Even a passing acquaintance with contemporary New Zealand film and visual art reveals the reach of Mansfield’s observation. The paintings of Colin McCahon, and the films of Jane Campion, Peter Jackson and Vincent Ward, for instance, are often soaked in this atmosphere of foreboding, depicting landscapes animated with an indefinable malice.

Rhythm folded in 1913, to be replaced by a new venture, the short-lived Blue Review, jointly edited by Murry and Mansfield. The collapse of this second journal caused Murry financial stress, forcing the couple to return to London from Paris, where they’d hoped to establish themselves as writers. The material insecurity of their lives, mixed with the volatility of their own natures, initiated a lifelong pattern of partings and reconciliations.

In one of the more notorious of these ‘flights’, Mansfield made a daring trip to visit her lover, Francis Carco, a writer and ‘committed bohemian’, in the French war zone. A fictional version of this trip can be read in Mansfield’s story ‘An Indiscreet Journey’, and Carco pops up again as the cynical narrator of ‘Je ne parle pas Francais’. Carco, for his part, made Mansfield the model of a character in his own novel, Les Innocents: ‘She was a small, slim woman, pleasant but distant, her large dark eyes looked everywhere at once.’

Katherine Mansfield, 1915 Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

Make It New

The outbreak of war in 1914 is commonly seen as the key event in the development of modernism, marking the end of the civilised ‘contract’ under which life had been lived. The old certainties of religious faith, sexual propriety and social stability seemed less authoritative, just as the artistic means of representing these aspects of society were changing. While the break is not so complete nor the timing quite so neat—there were movements across society and the arts prior to World War I which contributed to these changes—the War shook the European sensibility completely.

Leslie Beauchamp in uniform, 1915 Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

For Mansfield, whose beloved younger brother, Leslie, was killed in the war, everything changed: ‘I feel in the profoundest sense that nothing can ever be the same—that as artists, we are traitors if we feel otherwise: we have to take it into account and find new expressions, new moulds for our new thoughts and feelings.’

The emphasis on newness was everywhere—in Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, in James Joyce and Virginia Woolf and D.H. Lawrence. The artistic responses were different in each writer but the mood of overthrow linked them all. Joyce in Ulysses traced an elaborate and ironic Homeric myth over a single Dublin day and presented the novel with a fresh task: to map the mind and its wanderings. Eliot, with the spiritual poverty of contemporary life in his sights, constructed in ‘The Waste Land’ a scalding poetry out of literary allusion and religious symbol. These two took the high ground, writing works that required professorial assistance to unpick their densely patterned structures. (Mansfield herself was ‘revolted’ by the difficulties of Ulysses.)

D.H. Lawrence, on the other hand, though equally miserable over the state of industrialised city life, often railed in his work against the ‘civilising’ aspects of culture and sought the real in more primitive modes of sexual feeling. Mansfield was drawn to Lawrence—he was, after all, another outsider in the English literary world—but her journal also records her impatience with what she saw as Lawrence’s reductive view of human nature: ‘I shall never see sex in trees, sex, in the running brooks, sex in stones & sex in everything. The number of things that are really phallic from fountain pen fillers onwards!’

It was Virginia Woolf, in her psychological interest and her minute detailing of sensation, who was always closest to Mansfield.

Yet Mansfield had something beyond literary technique or cultured despair to drawn on. She had New Zealand. If estrangement was the oxygen of modernism, Mansfield, the colonial, had lungs that were filled as a birthright. She breathed alienation; she was also drawing in ‘newness’—the newness of New Zealand. Increasingly Mansfield would come to see this as a bounty to the artist rather than a burden, and to coax from its freedoms—the freedom from a literary tradition but also social and cultural freedoms as well as the freedoms of a sparsely populated landscape—her own freedom as a writer. The New Zealand she made up in ‘Prelude’ and ‘At the Bay’ is by no means escapist or classless or wishful, and yet the small, often petty domestic world of the Burrells is wonderfully enlarged by a sense of discovery and possibility. It is hard to resist the feeling that this is Mansfield’s own renewed sense of her country’s untapped potential.

Of course writers were not the only ones thinking about newness. The radical spirit in the visual arts was also crucial here. In 1910 Mansfield had seen the famous Post-Impressionist Exhibition in London and later recalled the effect Van Gogh’s Sunflowers had on her own practice. The painting, she wrote, ‘taught me something about writing that was queer, a kind of freedom—or rather a shaking free.’

Mont Sainte-Victoire (1904-06), Paul Cezanneb Courtesy: The Worldwide Art Gallery

The appeal of the Post-Impressionist lesson was clear. Cezanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire paintings, for instance, did not depict the mountain as it appeared on postcards. The scenes corresponded rather with interior images of the landscape that were constantly shifting with the light, with the movement of trees and sky; the paintings owed allegiance finally to the emotional response of the artist rather than to the ideal of a realistically rendered object. It was the thing as it was experienced rather than as it might photographically appear. The world was shown to be not fixed or static but elusive, fleeting, indefinite. It was up for grabs.

Again, in the context of the war-time experience, when society had failed to supply its citizens with security and authority, the idea of the supremacy of individual consciousness had obvious merit. If the exterior world was full of lies and false promises and death, the interior could be the place of authenticity. The recording, reflecting, dreaming ‘I’ came to the forefront of modernist writing. And this was the direction Mansfield’s writing naturally turned, not because it was fashionable but because it was felt. Even without the War, Impressionism’s philosophy and its methods suited Mansfield’s temperament and skills and beliefs.

The Dark-Eyed Tramp

Mansfield had always been concerned with notions of authenticity. As an early devotee of Oscar Wilde she was thoroughly versed in the idea of the ‘mask’—the false self, the social self behind which the ‘real’ self sat, watching and judging and rejecting. As a schoolgirl she had copied Wilde’s epigrams into her notebook: ‘Being natural is simply a pose—and the most irritating pose I know.’ She had taken from Wilde a kind of delight in the artificiality of the mask; if one had to hide, it may as well be cleverly and knowingly done. There is something of this in the playful nicknames she gave out and took on. In 1910, after attending a Japanese cultural exhibition, she took to wearing a pink kimono. During her brief Russian phase, she toyed with a fresh set of names for herself, ‘Katharina’, ‘Yekaterina’ and ‘Katya’.

Katherine Mansfield in Arabian shawl Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

This experimentation was a game; it was also in earnest, the classic moves of the outsider seeking to define a self in the new setting at the same time as she wished to escape definition. (She had also copied out Wilde’s dictum: ‘To realise one’s nature perfectly—that is what each of us is here for.’) More often than not the result for the colonial in London was a sort of mutual incomprehension. The English novelist Elizabeth Bowen registered this ‘misfit’: ‘Amid the etherealities of Bloomsbury she was more than half hostile, a dark-eyed tramp.’ In a journal entry, Mansfield gives full vent to this hostility: ‘No, I don’t want England. England is of no use to me . . . I would not care if I never saw the English country again. Even in its flowering I feel deeply antagonistic towards it, & I will never change.’

A Primer for Infants

In 1918 Mansfield published ‘Prelude’, the 60-page story which re-defined what a story could do and be. The action involves the Burnell family moving house from the town to the nearby countryside. Its autobiographical basis lies in the move Mansfield’s family made from Tinakori Road in Wellington to Karori, five miles away.

25 Tinakori Road, Wellington Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

Chesney Wolde, Karori, Wellington, NZ where ‘Prelude’ is set Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

Very little ‘happens’ but the story is full of vivid personal crises that crucially affect each character’s internal weather while leaving the atmosphere of amiable, conventional family life intact: the girl Kezia witnesses the killing of a chicken; Kezia’s unmarried and desperately timid Aunt Beryl recalls with horror coquettishly leaning against her sister’s husband when he was reading the paper; Linda, Kezia’s mother, fearful of being swallowed by family life, imagines the wallpaper is coming alive.

The story is told in twelve sections. We enter an individual consciousness for a few pages at a time before moving on to someone else. We glide from adults to children and back again, and from the family to its servants. The story is a miracle of fluidity.

In an ecstatic letter written around the time she was working on the story, Mansfield identified the form as her own invention and used the language of impressionism to suggest what she was aiming for:

“You know, if the truth were known I have a perfect passion for the island where I was born. Well, in the early morning there I always remember feeling that this little island has dipped back into the dark blue sea during the night only to rise again at gleam of day, all hung with bright spangles and glittering drops . . . I tried to catch that moment . . . I tried to lift that mist from my people and let them be seen and then to hide them again.”

The tenderness of this statement represents a dramatic shift in Mansfield. Though there was social commentary, ‘Prelude’, like its companion piece ‘At the Bay’, lacked the full protective armour of satire. Its insights were not arrived at through the observations of an outsider but mediated magically, it seems, through a floating narrator with access to the interior dramas of each personality. The intimacy was startling.

Mansfield felt vulnerable over ‘Prelude’ and this made her defiant: ‘And won’t the ‘Intellectuals’ just hate it. They’ll think it’s a New Primer for Infant Readers. Let em.’

In fact, when the story appeared, it was immediately seen as something very special in Mansfield’s distinguished fiction. The novelist Rebecca West considered it ‘a work of genius.’

Katherine Mansfield at Villa Isola Bella Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

The High Mind

Mansfield’s tuberculosis now caused her to move constantly between London and the French Riviera. These frequent separations from her husband allowed one aspect of her writing to flourish—letters. And taken with her journals, the correspondence now has a literary reputation to rival the fiction. The Nobel Laureate Patrick White once wrote that Mansfield’s letters ‘do jump at one . . . At their best they’re as perfect in their imagery as early morning.’ While the English poet Philip Larkin was impressed by the courage shown in the Journal and the way it showed ‘the high mind of the artist’.

In September 1920, Mansfield moved to the Riviera town of Menton, renting the Villa Isola Bella, and entering one of her most productive periods. Here she wrote a group of stories that rank with her best work: ‘Miss Brill’, ‘The Stranger’ and ‘The Daughters of the Late Colonel’. In December of that year, Mansfield’s second book of stories, Bliss and Other Stories, was published to enthusiastic reviews.

A few months later there was another move—this time to a mountainside chalet in Switzerland. Here she wrote some of her best-known stories: ‘Her First Ball’, ‘The Garden Party’ and ‘The Doll’s House’. There was also a majestic return to the characters and the style of ‘Prelude’ in ‘At the Bay’, a mini-epic, set over the course of a single summer’s day. Again, the New Zealand material proved most fertile for exploring issues of identity, belonging, and desire. ‘I long,’ she wrote, ‘above everything else, to write about family love.’

The Garden Party and Other Stories was published to great praise in February 1922, that watershed year of modernism which Mansfield’s book shared with Joyce’s Ulysses, T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and Rilke’s Duino Elegies. Each of these books planted a bomb under their respective genres, exploding reader expectations and enlarging literature’s scope for dealing with issues of individual consciousness. Mansfield’s detonation—since she worked in the field of the short story—was perhaps the least reported. It is also the case that unlike Joyce’s novel, Mansfield’s book still contained conventional narratives. These magazine stories ran alongside more experimental pieces, making it difficult to assess her avant-garde ambitions. Reviewers tended to see it as a strong collection rather than a radical work. They found ‘a dignity in its tragicomedy’ and noted that The Garden Party was a happier book than Bliss; one reviewer was moved to say that reading it convinced him ‘it is a good thing to be alive on this shining planet.’ It is only in more recent decades, as the short story has come to be seen as more deserving of close study, that Mansfield’s achievements and modernist affinities have been recognised.

In 1922 Mansfield should have been secure, buoyant. In fact, her health was getting worse and she was now looking for a miracle cure.

Day’s Bay, Wellington, setting of ‘At the Bay’ Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

The final months of Mansfield’s life produced little fiction, though she did complete ‘The Fly’, a portrait of her father and her classic statement on the futility of war. Disillusioned with conventional medical practice, Mansfield entered the Gurdjieff Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man at Fontainebleau in France.

Gurdjieff’s basic thesis was that the harmony of life had been disrupted by the pressures of modern living. His commune was an attempt to restore balance through a regime that included physical exercise and labour. Residents were encouraged to walk about with arms outstretched for long periods, take part in dances, and rise early in the morning to do communal work. None of this, of course, would have been an ideal regime for a TB sufferer. However, Mansfield’s TB was by this stage so advanced that Gurdjieff’s methods are thought to have had no effect on her decline. Mansfield, for her part, believed she’d found ‘my people at last’.

There was another aspect to Gurdjieff’s teachings which fits more promisingly with our sense of Mansfield than the gymnastics. Gurdjieff proposed that we had many ‘I’s’, not just one controlling ‘I’, a set of selves that could come into play at any time. Immediately, we see the appeal of this for Mansfield, whose work is filled with ambivalence about a permanent, fixed identity, and gestures always towards something more fluid and flexible and organic. It takes us right back to a letter she wrote in 1906, five years before she published her first book,: ‘Would you not like to try all sorts of lives—one is so very small—but that is the satisfaction of writing—one can impersonate so many people.’

These impersonations—in her journals, letters and stories—continue to exert their power and fascination. The contemporary English novelist and editor of the Oxford Companion to English Literature, Margaret Drabble, summed up Katherine Mansfield’s lasting radical spirit: ‘A symbol of liberation, innovation and unconventionality. Her life was new, her manners and dress were new, her art was new.’

Katherine Mansfield died on 9 January 1923 and she was buried at Avon, Fontainebleau. Her literary afterlife began quite soon. John Middleton Murry brought out The Doves’ Nest and Other Stories in June, followed by an edition of his wife’s poems, then by another story collection, Something Childish. In 1927, he edited the Journal of Katherine Mansfield and a selection of letters appeared the following year. These publications—as Antony Alpers wrote in his biography—tidied up Mansfield’s roughness, tempered her harshness by omitting certain passages and ‘sealed her in porcelain for twenty years.’

The sickly sweet Katherine created by Murry was difficult to swallow. In 1937, the American writer Katherine Anne Porter issued this warning: ‘She is in danger of the worst fate an artist can suffer—to be overwhelmed by her own legend.’ Fortunately, the legend was made more life-like by subsequent and fuller editions of her Journal and by more complete selections of her Letters.

The contemporary Mansfield is a figure of vivid contradiction—fiercely independent and pathetically needy, brilliantly bold and wretchedly repentant, terrifically ambitious and plagued by self-doubt. And these contradictions are most vitally present in all her thinking and writing about home, New Zealand. The despised place could also be the dream place. The empty place could be imaginatively rich. The unschooled land could teach the world. The undiscovered country could rise into view as Crescent Bay does in the famous opening of ‘At the Bay’ – the borderlessness of land and sea standing in for freedom and possibility:

“Very early morning. The sun was not yet risen, and the whole of Crescent Bay was hidden under a white sea-mist. The big bush-covered hills at the back were smothered. You could not see where they ended and the paddocks and bungalows began. The sandy road was gone and the paddocks and bungalows the other side of it; there were no white dunes covered with reddish grass beyond them; there was nothing to mark which was the beach and where was the sea. A heavy dew had fallen. The grass was blue. Big drops hung on the bushes and just did not fall . . .”

Katherine Mansfield, 1914 Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

References

Alpers, Anthony (1980). The Life of Katherine Mansfield, Viking.

Boddy, Gillian (1988). Katherine Mansfield: The Woman and the Writer, Penguin.

Lea, Frank (1959). The Life of John Middleton Murry, Methuen.

Lee, Hermione (1977). Virginia Woolf, Vintage.

Mansfield, Katherine (1981). The Collected Stories of Katherine Mansfield, Penguin.

Moore, James (1980). Gurdjieff and Mansfield, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

O’Connor, Frank (1985). The Lonely Voice: A Study of the Short Story, 1963, Harper & Row.

O’Sullivan, Vincent, ed., (1997). Katherine Mansfield’s New Zealand Short Stories, Penguin.

Vincent O’Sullivan, ed., (1988). The Poems of Katherine Mansfield, OUP.

Scott, Margaret, ed., (1997). The Katherine Mansfield Notebooks, 2 vols, Lincoln University Press and Daphne Brasell Associates Ltd.

Stead, C.K., ed., (1977). Katherine Mansfield: Letters and Journals, Penguin.

Claire Tomalin, (1988). Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life, Penguin.

Websites:

Katherine Mansfield/New Zealand Literature

http://www.vuw.ac.nz/nzbookcouncil

Mansfield entry in Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature and other information/links on New Zealand writers and books

http://www.arts.uwo.ca/~andrewf/zoetropes.htm

On-Line edition of Bill Manhire’s illustrated work of fiction, The Brain of Katherine Mansfield, plus links to NZ Lit sites

Virginia Woolf

http://www.orlando.jp.org/vww

Virginia Woolf Web: biographical and bibliographical information plus links

Modernism in Visual Arts

http://www.arthistory.net/artist.html

Introductory course in modernism, featuring leading artists, Cezanne, Van Gogh et al.

What a very sad story, At first life was happy for Katherine but now it has gone to dust ever since her brother died from the grenade incident.

I appreciated the detail in this - I will be using to plan my Year 13 study of KM.

Excellent piece about the writer

I think you've written an outstanding and far reaching overview of her life. I've become dazzled by her writing and it's wonderful to know more about the artist and her development. I'll certainly be looking to find all of her writing and proudly add them to my library. Thank you so much

What fantastic insight into Katherine Mansfield's life. I am currently taking a BEd degree at University of Hertfordshire and have been given an assignment to do which I am researching. It is The Voyage and I would love to get a more deeper understanding of what she was trying to say about herself through this story. Please could you send me information on The Voyage. You have given me a great perspective of her work and life through this website. I am most definitely going to read more of her stories. Many thanks, Mrs J Slome. tonylynwood@aol.com Student Hertfordshire, England

I love the quotes you have displayed from Katherine Mansfield (one of my favourite NZ authors, along with Janet Frame) and Vikings of the Sunrise – a very powerful metaphor. Helpdesk Analyst London, England

I am very excited to find so much information offered here. Katherine Mansfield was one of my favourite authors when I was a college student. In fact, my thesis for my master's degree in 1986 was "A Thematic Study of Katherine Mansfield's Short Stories". I really did a lot research then and photocopied as many materials on this author as possible. Before I set down pen to write my thesis, I went to Beijing, Shanghai and Hanjing, visiting major libraries and universities in order to get as much information as I could. As your site says, there have been a lot of literary studies in China in the last century, maybe more than anywhere else, I guess. Thank you again for the work you have done here. College Teacher China

I have a site were texts of several writers are published http://www.releituras.com). Here, in Brazil, Katherine Mansfield has a lot of readers who like her novels. A great Brazilian poet, Vinicius de Moraes, wrote a poem to her. I'm sending it to you in Portuguese and English. If you like, put it in her page. SONETO A KATHERINE MANSFIELD O teu perfume, amada - em tuas cartas Renasce, azul... - são tuas mãos sentidas! Relembro-as brancas, leves, fenecidas Pendendo ao longo de corolas fartas. Relembro-as, vou - nas terras percorridas Torno a aspirá-lo, aqui e ali desperto Paro - e tão perto sinto-te, tão perto Como se numa foram duas vidas. Pranto, tão pouca dor! tanto quisera Tanto rever-te, tanto!... e a primavera Vem já tão próxima! ...(Nunca te apartas Primavera, dos sonhos e das preces!) E no perfume preso em tuas cartas À primavera surges e esvaneces. (Vinicius de Moraes) SONNET TO KATHERINE MANSFIELD Your perfume, beloved - in your letters Reborn, blue...- it's your afflicted hands! I remember them white, light, withered Pending along abundante corollas. I remember them, I go - in lands gone through I inhale it again, here and there awakened I stop - and so close I feel you, so close As if in one we had two lives. Weeping, so little pain! so much I wished So much to see you again, so much! ... and the spring Already comes so close! ... (will you never part Spring, from dreams and from prayers!) And in the imprisoned perfume in your letters To the spring appears and evanesces. (Translation: Regina Werneck) Regards, Arnaldo Nogueira Junior. Mais de 130.000 visitas em Junho/2001! PROJETO RELEITURAS Os melhores textos dos melhores escritores http://www.releituras.com Arnaldo Nogueira Junior Brazil

"Have just finished the new Hero piece by Damien Wilkins on Katherine Mansfield. It is brilliant and totally right for nzedge. I knew of her but not about her. Now I can add it to my great New Zealanders list. Yet even more enjoyable is the way that the importance of New Zealand is woven into her story. When I read that Mansfield left these shores at 20 I thought we had another Russell Crowe on our hands (no disrespect to Maximus but fighting over whether he is Kiwi or Aussie seems a bit grasping to me). But no. Damien showed that New Zealand and the Edge suffused the work and life of an incredible women. Edge is an attitude and what unites us wherever we ply our trade. Thank you, and your team, for another great installment and reminder why we our so lucky. Very cool." Harry Auckland, New Zealand