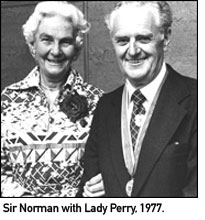

Years ago, it would have been the late 70’s, and I was working on an arts employment project with Para Matchitt and Jacob Scott at Otatara, the arts campus of the then Hawke’s Bay Community College, I ran into an energetic little old Pakeha man who had come down from Opotiki fairly brimming with ideas about Maori co-operative enterprises. He introduced himself as Norman. In fact he was Sir Norman Perry KT, MBE.

Norman was a showing around a little black vase. It had been carved with a primitive and chunky koru design after it had been thrown, and then had been fired in sawdust. It was basic, somewhat ugly. Nevertheless he talked energetically to Para and Jake about the potential for such items in the global tourism market. It was all neither here nor there to me (although, somehow, I ended up with the vase – it sits in front of me now), but what struck me at the time was the deference shown by Para to this old man.

It turned out that Norman Perry had been the secretary and assistant to Sir Apirana Ngata He was a member of the ‘Tribal Work Party’ with Sir Apirana from 1938-50, and facilitated numerous co-operative ventures – especially through the Whakatohea Trust Board, for the men who had returned from WWII.

Norman Perry was a non-Maori in the Maori Battalion. He admired the synergy that arose when a Maori organisation hit its straps. He was respectful of the warrior gene, grateful for it in those grim times. He used to commend me to the tactic of reconnoiter. That, he reckoned, gave the Maori Battalion an edge. “When facing the enemy”, he would tell us willing listeners, “keep your powder dry”, and then, when battle was committed, “wait till you see the whites of their eyes”. The old bloke was seriously wounded in the Italian campaign and the resulting lingering bits of shrapnel bore the blame for any of the aches and ailments of the latter stages of his 92 years.

Norman Perry was a non-Maori in the Maori Battalion. He admired the synergy that arose when a Maori organisation hit its straps. He was respectful of the warrior gene, grateful for it in those grim times. He used to commend me to the tactic of reconnoiter. That, he reckoned, gave the Maori Battalion an edge. “When facing the enemy”, he would tell us willing listeners, “keep your powder dry”, and then, when battle was committed, “wait till you see the whites of their eyes”. The old bloke was seriously wounded in the Italian campaign and the resulting lingering bits of shrapnel bore the blame for any of the aches and ailments of the latter stages of his 92 years.

After the war through his efforts in the Presbyterian Church he became a member of the International Laity Committee of the World Council of Churches (1955-1958). He was the leader of an Ecumenical Church Vietnam Peace Mission and helped initiate peace talks between Buddhists and Christians in North Vietnam and South Vietnam in 1965.

He was a friend and contemporary of Rewi Alley – he would regale those of us who were in the work cooperative movement with stories of ‘gung ho’ – and was a trustee of the Rewi Alley ‘Shandan School’ from 1984.

Norman often joked that, as a young Presbyterian, he had the idea that he would help Maori change from their heathen ways. In fact he became immersed within, perhaps even captured by, the Ringatu religion and the teachings of Te Kooti. I was grateful for his help when the Rasta troubles broke out on the East Coast in the 1980’s. I was running the Group Employment Liaison Service in the Department of Labour and part of my brief involved these guys. To some degree the Ruatoria Rasta were entwined within a mix of herb and bible and the more prophetic teachings of Te Kooti. They were intelligent, steeped in their Maoriness, fit, tough and part of a rugged landscape. When these elements arced, awful and disturbing things happened. Norman used his familiarity with Te Kooti’s teachings to help those young Rasta firebrands who were imprisoned to find within Ringatu a pathway to peace and understanding. He would go to Paremoremo and would sit down with Chris Campbell, the Rasta leader of the time, and others, and talk in his humble but deeply knowledgeable way.

Norman Perry, it turned out, was to play a significant role in my life, as he had, and would, in the lives of many others. He was a member of the Roper Commission and the driving force behind many initiatives around prison reform, proclaiming that rather than ‘rehabilitation’ many prisoners simply needed ‘habilitation’. They had never actually received instruction in how to live, as it were.

Norman enlisted me in his various projects and quests through the Mahi Tahi Trust. I’d receive a kaumatua-like call, a message, an instruction to meet him at a certain time at his hotel or at some senior public servant’s office. His tactic was to treat you as if you were playing solo violin, whereas, as you would discover later, you were simply playing one small part within a very large orchestra.

As you may have gathered Sir Norman Perry has passed. He died in Auckland on August 2nd. I agreed with senior members of the Mongrel Mob Notorious chapter to meet at his home in Pt Chevalier Auckland so we could pay our respects before we met to follow through on some initiatives around P-addiction recovery.

Taape and I drove up from Hawke’s Bay on Saturday. It was a miserable wet day and we arrived at the house in Pt Chevalier at about 5.00pm with the light staring to fail. Norman was lying in state in a little whare-styled building at the bottom of the garden. It was a seaside section and the whare looked out over the Waitemata. Below it were mature pohutakawa and despite being in the heart of our most populous city the lights seemed far away and it felt like being at a summer bach on the coast.

That evening several gang leaders spoke, their grief apparent, their stories authentic: how Norman had intervened in their lives through his visits to them in prison; how they were trying to fulfill the vision he had shared with them. It was poignant. It expressed a fulfillment of the Christian possibility of redemption and it celebrated hope. It was humbling.

That evening also made me proud, proud to be Pakeha. I recognised that this old man’s death marked another significant layer of paving on the pathway of our tribe, Ngati Pakeha. Norman’s values help spell out the emergent values of our tribe; respect to our tuakana and Treaty Partners, nga Maori; love of Te Reo Maori; love for people, particularly those who carry a burden; love of peace and preparedness to do the hard yards to win it.

After the korero I sat down around Norman’s dining room table with Roy, Bones, Edge and other MM Notorious council members, and we discussed their current project to develop addiction recovery services and the support that I can bring. The old man would have been well pleased.

There’s always a ‘yeah right’ aspect to telling others about these issues. Recently I was at the tangi of a mate’s dad and I ran into a senior policeman who I know. In my experience he has been a fair and reasonable man, and I like him. He wanted to yak. He’d been to a conference about alternatives to prisons and had seen a presentation by Edge and Roy and the Mongrel Mob guys. They were outlining their aspirations; breaking the cycle, expressing the desire for a lifestyle based on whanau and on increased engagement with their Maoritanga.

The cop asked me if ‘this was for real?’ For him it didn’t ring true. “Am I just being a cynical cop or am I missing something?” he asked. I had to tell him. Brother, I myself fuck up. I know I’m true in my heart about pro-social change but from time to time, predictably with a skin full of piss, I fuck up. However, equally, over time, my directionality is clear and observable and, I’d hope, more good than bad.

Accordingly, based on what I see, and conceding that I don’t know what I don’t know, just as with the Black Power, I’m going to take the Mob’s drive to socialisation at its face value and support it. As this blog records, these aren’t one off PR events but rather a consistent expression of desired direction, time after time.

At street level, the drive to focus on whanau, to move from an exclusive focus on brotherhood to an inclusive focus on family-hood, is a bold one, and is not a universally accepted proposition. But the dialogue is on. “What does it mean to be a gang member today?” Or, perhaps, as a point of possible differentiation from the international criminal conspiracy, “what does it mean to be a Maori gang member in Aotearoa today?”

When I ask that question I seldom hear ‘committing crime’ as a purpose for a Maori gang. Generally I hear words like ‘whanau’ connected with housing and education and a good job and all of the things you’d hope that people would aspire for in their whanau ora. If most of the underlying aspirations are pro-social then is forming a gang the way you’d go about achieving your aspirations? If Maori gang member aspirations tend to be couched in terms of others, ‘whanau’, then are the two things, gang and whanau, irreconcilable? If the whanau ora objective cannot be served by ‘gang’ then what is the alternative?

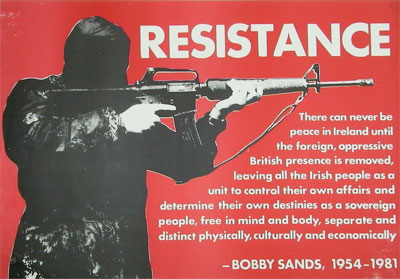

Of their own volition the IRA have laid down their weapons and dissolved their organization. Being a resistance army no longer met their needs. What extraordinary shift in paradigm did that entail?

The same has happened in Spain with the ETA (Euskavi Ta Askatsuna) the former Basque revolutionary militia. Circumstances have changed. In light of the issues I am presenting is it time for the current indigenous street warriors of Aotearoa considering a new street level configuration and a new sense of purpose?

This is a hard korero for many gang brothers to hear, however I’m being neither disloyal nor disrespectful in raising the issues. Discussing these things is an act of belief, a belief in each other’s potential. I acknowledge however that whilst I might get some traction with this korero amongst my own age cohort, amongst the younger members – who have the most potential but want to find their own warrior path – I may well just be another old granddad sounding off.

In the meantime I’ll live with the ambiguity. Harvard University Professor, Amartya Sen reckons that ambiguity is in the nature of human life and that in social investigation it is more important to be vaguely right than to be precisely wrong. Directionality, I’ll settle for directionality.

The social investigation of the moment has been catalysed by the short and tragic lives of the Kahui triplets, one of whom died at birth, and the surviving brothers who were both murdered soon after. The realisation that the Kahui whanau (bizarrely kahui means ‘cluster’ in Maori) were collectively earning a couple of grand a week in benefit payments created as much furor as the deaths of the tamariki themselves. The ensuing moral panic has the Ministry of Social Development carrying a big stick and looking for ‘clusters’ of Kahui in towns nation wide.

Don’t waste your resources. They are already known. These are the people who feature in these columns, the people who we call ‘nga mokai’ and about whom I have shared much over the past couple of years.

You may have witnessed that in the instance of the Kahui whanau their sense of cultural identity as Maori, as reported by Pita Sharples, was not strong enough to enable the normal behaviour expected by Maori of themselves and of each other: aroha ki te Tangata, the Maori anchor of concern for others beyond ourselves; the demonstration of putahi (interconnectedness), and; provision of manaakitanga (unqualified caring).

In these columns I have described, time after time, the thirst that nga mokai whanau have for their Maoritanga. I think the challenge of the moment is less a matter of focus on suppressing undesirable behaviours and more of a matter of focus on enabling people to break out of their trapped lifestyle and to recreate their identity, collectively as members of a family, and individually, as a human being, as Maori person with whakapapa to the gods, Te Ira Tangata.

I sense we will find the best pathway towards mokai whanau ora through a contemporary expression of being Maori, of being Maori New Zealanders. That said, I accept that there will be many paths and that directionality is the key issue rather than the arguing over the ‘best’ route. In any case it means we need to focus on the positive and the doable rather than trying to plug the vortex of failure, which has been the general thrust of the last four decades of government policy as regards Maori. A change is afoot. Whilst there was recently a great deal of political and media attention fixed on the Ministry of Maori Development (Te Puni Kokiri) because they didn’t ask for an increased budget (this is a problem?), little attention was paid to a fundamental shift that the organization has taken in its approach to policy development. I must declare that Te Puni Kokiri are a client of mine from time to time. That advised, I’ll stick to my guns. Rather than backfilling deficit Te Puni Kokiri (TPK) have reframed their policy paradigm to one of ‘potentiality’. This focuses on Maori success in Te Ao Amuri – the future, and in Te Ao Whanui – the global economy.

I’ve trotted out my little sayings to you before; ‘Focus on the good’ (Tareha) ‘Assume the best’ (Maslow) and ‘You’ll see it when you believe it’ (Alinsky), so you might understand that a paradigm based on ‘Maori Potential’ resonates with me. Under their own shibboleth, ‘Maori succeeding as Maori’, TPK are assuming the inherent capability and aspiration of Maori people to make choices for themselves in way that supports their cultural identity and contributes to optimal yet sustainable life quality. The principles and values have been conflated into a Maori Potential Framework.

Download Potential Framework PDF

Source: Karauria (2005) Wellington: Te Puni Kokiri

This Maori Potential Framework is a profound bit of thinking and it augurs well not only for the development of Maori communities but for the nation at large. Sustainable Maori success is defined as a

‘level or state of success that once achieved can be sustained over time to the extent that it becomes universally accepted, recognized and defined as a normal or ordinary state of being for Maori’

(TPK 2006)

The pivot for development is whanau, and these whanau might be at any of the vertical ‘whanau potential’ stages on the Maori Potential Development Outcomes Matrix rendered graphically below.

Download Whanau Development PDF

(Karauria, 2005: Wellington TPK)

Now this isn’t the time or place to go through the whole framework, but the overeall notion of ‘being successful’ as being the normal expectation for Maori fills me with hope.

This isn’t Maori griping and wallowing in a sense of injustice and frustration but a profound statement of future purpose. Maori are moving on. As part of my school work I’ve been reading excerpts from an as yet unpublished doctoral thesis (J. Vanderpyl, 2004. University of Auckland), which in part looks at the struggles of NZ feminist service groups (Rape Crisis, Women’s Refuge).

When it came to develop a relational framework based on the Treaty of Waitangi Vanderpyl contends that, during the 1970’s and 1980’s, consciousness raising about Maori, and the implications of the Treaty of Waitangi, influenced Pakeha women in these service groups to consider Treaty issues, Pakeha privilege and domination, and the practical application of bi-culturalism to their organisation.

This proved to be a very difficult journey for many Pakeha feminists. At a gut level there were unspoken expectations of a homeginity based on a common global feminist identity. However many Maori feminists expressed their sense of ‘mana wahine’ as being a member of a collective experience united in Maoriness rather than gender or sexual orientation. This seemed to reduce the centrality of the feminist ideology and challenged the notion of a common experience. The common Maori experience is based on whakapapa and whanau and therefore includes ‘mana tane’, men, as part of the equation. The Maori feminists required an ‘and and’ approach and this whilst challenged the Pakeha feminists the Maori feminists also held true to their feminist ideals and worked at both structural changes within their organizations and cultural change to carry their message. I think it’s a great story because it demonstrates the possibility of walking in two worlds.

I mention this in the context of the recent proclamation by the Prime Minster about the rewriting of protocols for powhiri. Basically a thousand years of customs has been re-appropriated to suit political correctness. If Helen Clark (Labour) and Judith Collins (National) think they’re striking a blow for Maori women by attacking seating arrangements at powhiri they’re not only wrong but demonstrate that they just don’t get it at all as regards tikanga Maori.

The recent big seizure of methamphetamine at our borders (with an estimated street value $135m)- thanks Customs, thanks coppers, you’ve done a good job and stopped one big load of grief hitting Kiwi communities – demonstrates both the scale and the global nature of the problem we currently face with P.

Firstly the nationality of the alleged traffickers confirms that Aotearoa is a distribution target for offshore international criminal syndicates. The consequence to Kiwi communities is of no regard to the importers.

This most recently intercepted shipment has reportedly been preceded by several earlier successful importations last year and earlier this year. That helps explain the successive waves of product that have flowed through the P market and the consequent P related destruction that we have been encountering over the last year.

Secondly because of the huge amount of product being moved, and thus the great wealth generated from a successful operation, the stakes are high. History is filled with stories of criminal greed and consequent ruthlessness. The nature of the weaponry seized during the recent bust demonstrates that the importing syndicate was prepared to use deadly force. On its own this is worrying. But even more so, taking into account the state of high arousal associated with P use, is the evidence that these attitudes are being mimicked locally further down the distribution chain. For instance in Wellington just a few months ago we saw the seizure of military style weapons, hand guns, a grenade and power gel.

The choices are stark and sitting back is not an option. We need to hold the line, continue the hard work at the ‘whanau ora’ coal face and be prepared to look after each other when the going gets rough. On the other hand I’m seeing a certain sense of calm return to the street. The committed P users have tended to shift away from the ‘burn’ to use of the needle as a way to take their fix. This form of ingestion seems to enable users to tolerate the substance without spinning out as they may have when using a pipe. Use of a needle sorts out the players from the dabblers. There seems to be a psychological barrier to using a needle and a person has to acknowledge the reality of their addiction in doing so. Availability of supply currently seems to be down – due I presume to the good detection work at our borders – and so I presume we’ll see a return to the homebake for the desperate.

I’m a dozen blogs in, this one written during the latter part of the period known here in the rohe of Ngati Kahungunu as ‘Matariki’, the rising of Pleiades and the commencement of the Maori New Year. Matariki is celebrated throughout the Pacific, but elsewhere it occurs at the end of the season, not the beginning. Those early voyagers to this edge we call Aotearoa may well have decided that the sometimes grim winter weather needed a celebration (hey, hey, let’s call it Christmas) or maybe after a few years here they figured that this was the point of the year at which you’re best to get rid of old stock, clean up, and prepare for the new season of growth.

I’ve a fair bit of cleaning up to do on the personal front. The study (Master in Social Practice) I’m currently completing entails learning about self-critical reflection and damn, these processes have left me not very happy with myself, conscious of my personal paradoxes and contradictions, and embarrassed by my weaknesses and my propensity to fuck up when pissed.

And that is when I must beware

Of the beast in me

That everybody knows

They’ve seen him out dressed in my clothes

Patently unclear

If it’s New York or New Year

God help the beast in meBeast in Me: Nick Lowe

Never mind the warrior gene, what about the bloody Irish gene? Context counts and you might forgive some freaky behaviour in the environment in which I operate. Nevertheless my values have eroded or maybe morphed. There are gaps between what I espouse and what I do. Slap yourself, Denis! Clean up your act man!

I’m on to it.

Arohanui. D.

Source: www.astronomynz.org.nz