First, we’ll visit the ossuary. Tam Wong Shi, my friend Harry’s mum, reached her terminal milestone of 103 years a few weeks ago. Her journey in life sounded tough: married in feudal China at 17 and then not to see her husband again for some 20 years. During the war Wong Shi was on a boat that struck a mine in the South China Sea and had to cling to the side of the vessel for three days. She was amongst the last wave of Chinese to flee after the Maoist Revolution. Ever the matriarch, the workload of family and the family business, a restaurant in Riddiford St, Newtown, Wellington, fell mainly on her shoulders. Mr Tam had a little opium habit which distracted his efforts. It took an extraordinary strength of character on her part to satisfy the needs of three children and a marginal business. She had what it takes, and I recognise the mother’s capacity and commitment in her son. After her death she rested for a time at Harry’s home in Wainuiomata with her Maori grandchildren and a stream of visitors until the auspicious date and appropriate time for burial. Farewell into the long night e te kuia.

Chinese Symbol for Death

Across to the west of Te Ika a Maui, in the protective shade of his tipuna maunga, Taranaki, brother Joe Dread succumbed to cancer. Joseph Tommy Ngaheu was born 12 July 1956 and died on July 4th 2008, after a full on life of work, pubs, gangsta lifestyle and partying. He was taken from his marae to the Patea cemetery followed by a long cortege that stretched through the township. His coffin, covered with a funeral pall of a blue cross on white lace, was born high by his Black Power brothers, as he was saluted with challenges from taiaha-bearing warriors and with haka from his club mates. Although the guys all bear gang insignia and use the odd indecipherable phrases—Yo Fuck Yo and so forth—that merge traditional reo with contemporary shibboleths—in reality they are pretty much following the rituals that their ancestors have performed over time. Politicians condemn the brothers for bastardising tikanga Maori yet the various millennial movements—Pai Marie and Ringatu for instance—took on icons ideas borrowed from foreign cultures. Te Kooti’s flag Te Wepu—the whip—carried designs created by Mother Mary Aubert—a French Catholic nun. The Hau Hau used the Nui Pole and rituals drawn from British Army drills. Rua used icons drawn from a pack of cards. These globally derived fashion statements don’t override the core strength of the indigenous culture. Yes the gang and its accruements are imported concepts but these folk remain Maori, tuturu, through and through, and don’t let anyone try to convince you otherwise. So, over Joe’s grave we sung hymns, Mo Te Hunga Kua Okioki and Ma te Marie. Rest easy, brother Joe, haere atu ra.

Across to the west of Te Ika a Maui, in the protective shade of his tipuna maunga, Taranaki, brother Joe Dread succumbed to cancer. Joseph Tommy Ngaheu was born 12 July 1956 and died on July 4th 2008, after a full on life of work, pubs, gangsta lifestyle and partying. He was taken from his marae to the Patea cemetery followed by a long cortege that stretched through the township. His coffin, covered with a funeral pall of a blue cross on white lace, was born high by his Black Power brothers, as he was saluted with challenges from taiaha-bearing warriors and with haka from his club mates. Although the guys all bear gang insignia and use the odd indecipherable phrases—Yo Fuck Yo and so forth—that merge traditional reo with contemporary shibboleths—in reality they are pretty much following the rituals that their ancestors have performed over time. Politicians condemn the brothers for bastardising tikanga Maori yet the various millennial movements—Pai Marie and Ringatu for instance—took on icons ideas borrowed from foreign cultures. Te Kooti’s flag Te Wepu—the whip—carried designs created by Mother Mary Aubert—a French Catholic nun. The Hau Hau used the Nui Pole and rituals drawn from British Army drills. Rua used icons drawn from a pack of cards. These globally derived fashion statements don’t override the core strength of the indigenous culture. Yes the gang and its accruements are imported concepts but these folk remain Maori, tuturu, through and through, and don’t let anyone try to convince you otherwise. So, over Joe’s grave we sung hymns, Mo Te Hunga Kua Okioki and Ma te Marie. Rest easy, brother Joe, haere atu ra.

A day after Joe’s passing my Greek brother and friend, acclaimed architect, Paris Magdalinos died, felled by an aggressive and sudden cancer. Paris Magdalinos was born in Nazi occupied Constantia, Romania, in May 1942 during an Allied bombing raid. I believe that this gave Paris the notion that his task on earth was to create buildings, not destroy them, but nevertheless, to always reverberate with explosive flourishes and startling colour—in particular his favourite trinity of deep blue, red and rich yellow—boom! The Magdalinos family initially fled to their native Greece and thence to New Zealand as refugees in 1953. Paris eventually settled in Napier, met and married the lovely Bobbi, and sired three fine children. I met Paris not long after I married Taape, and we became firm friends. In the mean days of unemployment in the mid 1980’s, as part of a scheme to ‘make work’ he designed a roof to cover Te Huinga, the hall that stood at Waiohiki. Magdalinos’ design absolutely transformed the building, turning it from an incomplete box into a strong proud gatherer of people. But equally, the brilliance of the man was contained in the overarching detail, not only of the building design, but also its overall context, including the people who would use the space and who would build it. Accordingly, as we had a virtually voluntary and relatively low skilled workforce, Paris designed a very simple construction with profound Maori lines.

Paris had flatted with the famous Maori architect John Scott and perhaps this, mixed with his Greek heritage, provided the platform for his relationship with Maori. When we first welcomed him to Waiohiki—for what was to become the first of 30 years of regular meetings—uncle Jock Pene was on the papepae. That Paris was Greek was all that mattered. Uncle Jock was a member of the 28th Maori Battalion and the good relationships developed between Greek and Maori through World War 2 meant that was that. Greek was good. Paris was a welcome manuhiri, as well as being a respected tohunga in his own right. Besides designing the Big House for Ngati Hinewera (a 21st Century approach to kainga living fully covered in the Nga Kupu Aroha blog December 2004). Paris has recently completed the design of the new meeting house and dining room facilities at Waiohiki for Ngati Paarau. Although Paris will never see the buildings erected the brilliance of his design means that he will stay with us for a long time to come. That is the real test of genius—timeless enduring value. Architecturally Paris was a dynamo, winning 58 New Zealand Institute of Architecture Awards, two Supreme National Awards for Architecture and the rarely given NZIA Award of Honour. Nic, Paris’ youngest son, rang me to tell me of his dad’s sudden ill health. I took my brother Laurie’s rosary beads over to Cranford Hospice and sat beside my friend and recited the ‘sorrowful mysteries’. In his inimitable style and eye for detail Paris had stipulated the form and manner of his funeral arrangements. After talking things through with Bobbi and the whanau it became apparent that it would be appropriate to bringing his tupapaku out to rest on the marae at Waiohiki for a time. And so, after Paris slipped into the night I spoke with our family chief, Tipu Tareha, who did the round of the kaumatua and it was all deemed to be so. Since the fire that destroyed Te Huinga, now some seven years ago, we have no hapu buildings to speak of, although we sit in the shade of 700 years of architecture in the engineered landforms of Otatara. We rallied up marquees and Mane and his team of the Hawke’s Bay Black Power put them up. We set aside a separate marquee space as a makeshift dining area and stocked it well with Alwyn Corban’s Ngatarawa Silks Merlot, a range of superb cheese and antipasto and olives and stuffed vines leaves and anything I could remember Paris being fond of.

Cosmopolitan marae kai – Photo by Richard Brimmer

The Mad Butcher sent his little mobile barbecue vehicle out with a load of sausages. As a repast it strode across the culinary cultural divide, an unusual hakari. With the food and shelter covered the only thing missing was art to uplift the spirit and please the eye. This was provided in trumps by Para Matchitt and Jacob Scott. Waiohiki sits on a rise and Para and Jake installed a number of large sculptures that made use of the landscape so that as the visitors approached the figures seemed to dance across the skyline. Jake provided a series of three metre high multi dimensional manaia figures.

Para brought out works from his Te Wepu series with their creative application of Mother Aubert’s primitive icons. One—this of Para’s own origination—was a four metre high sculpture in bright red steel of Te Kooti on a rearing horse—considering history, an unusual visitor to Waiohiki.

Te Wepu series – Para Matchitt – Photo by Richard Brimmer

Te Kooti series – Para Matchitt – Photo by Richard Brimmer

Another, a raised tabernacle affair, was constructed of chrome punctuated with deeply coloured red and blue window spaces with a cross motif—very Greek. One of our local artists from the Waiohiki Creative arts Viallge, Nathan Rose, created, in Mediterranean blue, a simple hand crafted epitaph, which sat above the space where Paris was to be laid during the period of the hari mate. It was a quote from Aeschylus’ The Oresteia

“Sing Woe, Woe! But Let the Good Prevail.”

and was written both in Greco script and in English. It resonated with Waiohiki chief Tareha Te Moananui’s exhortation to the Fourth New Zealand Parliament to

“Focus on that which is good.”

Paris would have loved it.

Paris’ final site visit to Waiohiki – Photo by Richard Brimmer

He Whanau Pani – Photo by Richard Brimmer

So we gathered. The Karanga, the mournful call was given by Kath Hawaikirangi, and our friend and brother, resplendent in a bright blue coffin, dressed with the flag of Greece, was brought to us up the little rise, by his grieving whanau, colleagues, and friends. This was his last site visit. It was an honour and a gift to have Paris amongst us. It was also a commentary on the growing bicultural capacity of our nation. After the formal welcome from Labour Hawaikirangi and Albie Gray, and the replies from Tiwana Aranui and our Maori speaking MP Chris Tremain, we broke for a while to eat and drink, to make communion with Alwyn Corban’s fine wine, quality cheese, and sumptuous Greek food.

Denis reads Jimmy to Paris – Photo by Richard Brimmer

Then, back in the whare mate, we made further speeches, sang songs, and read poems. And when we had done, Paris was lifted by the men of the Waiohiki hapu, Ngati Paarau, and carried reverentially to the hearse. The following day we gathered in the Napier Cathedral for the final rites. I had forgotten the beauty of this building, its uplifting design, soft pastel colours, and grand sense of spiritual space. Paris’ rich blue coffin, now covered in Irises, was brought in to the church to the March of the Hebrew Slaves. More speeches and prayers were said. Our local, opera singing, Maori barber, Laurence Mane, sang “E lucevan le stele” from Pucini’s Tosca and as the coffin was carried out of the catherdral to the hearse the rhythmic slap of the Kahungunu haka, “Tika Tonu” echoed through the vestibule. Haere ra e taku tuakana Pakeha, ko Paris, haere, haere atu ra…

It is Te Wiki o Te Reo Maori Maori Language Week. We have well and truly moved on since Syd and Hanna (Hemara) Jackson battled for the reo back in 1972. This year the theme is around speaking Maori in the home, and every morning the dulcet tones of the national programme presenters kick off the day with Te Reo like a shot of aural caffine. Good on you Radio New Zealand. Having won the right to speak Te Reo Maori as a human right as well as a Treaty Right, and having the language positioned as an official language of the nation, the debate amongst Maori is now around quality over quantity. But, for my part, a living language will morph and change and that is a sign of its vitality and relevance. Another is its presence in the cyber-world with Microsoft applications and on-line dictionaries and the like. Expect to hear more Maori. Its cadence is pleasing to the ear. Rappers love it because words always end with a vowel, making rhyme easier, and we all know the our national anthem sounds a helluva lot better in Maori than in English.

In South Auckland recently on a wet wintry day 15,000, mainly Asian people, marched because they experience fear of crime and racial intimidation in Aotearoa. It will be cold comfort to them that proportionately most victims of crime and violence are actually Maori and other Polynesian New Zealanders. Equally Asian people probably get hit with hand-bag snatches and the like, not particularly because of hate for their race, but because of their own personal habits and beliefs about authority structures and, apparently, banks, which make them an easy mark for equal opportunity criminals. However whilst perception may be reality for many Asian New Zealanders, in my view, their perceptions have been clouded by the beating drums of political hype, which once started are hard to silence. I thought the suggestion of the Asian march organisor, Mr Low, that he invite the Triads to play a vigilante role if the cops couldn’t handle the situation, was a dumb arse comment. However for a relative nobody the bloke may have been so buoyed by such a turn out that, perhaps, despite his recent recantations, he let the cat out of the bag about the real time presence of a subterranean criminal order amongst the oriental members of Tangata Tiriti. If the Asian Anti Crime Group wanted to make an immediate impact on the reduction of crime in New Zealand all they need do is focus on their own kith and kin and help stem the flow of methamphetamine into our shared land.

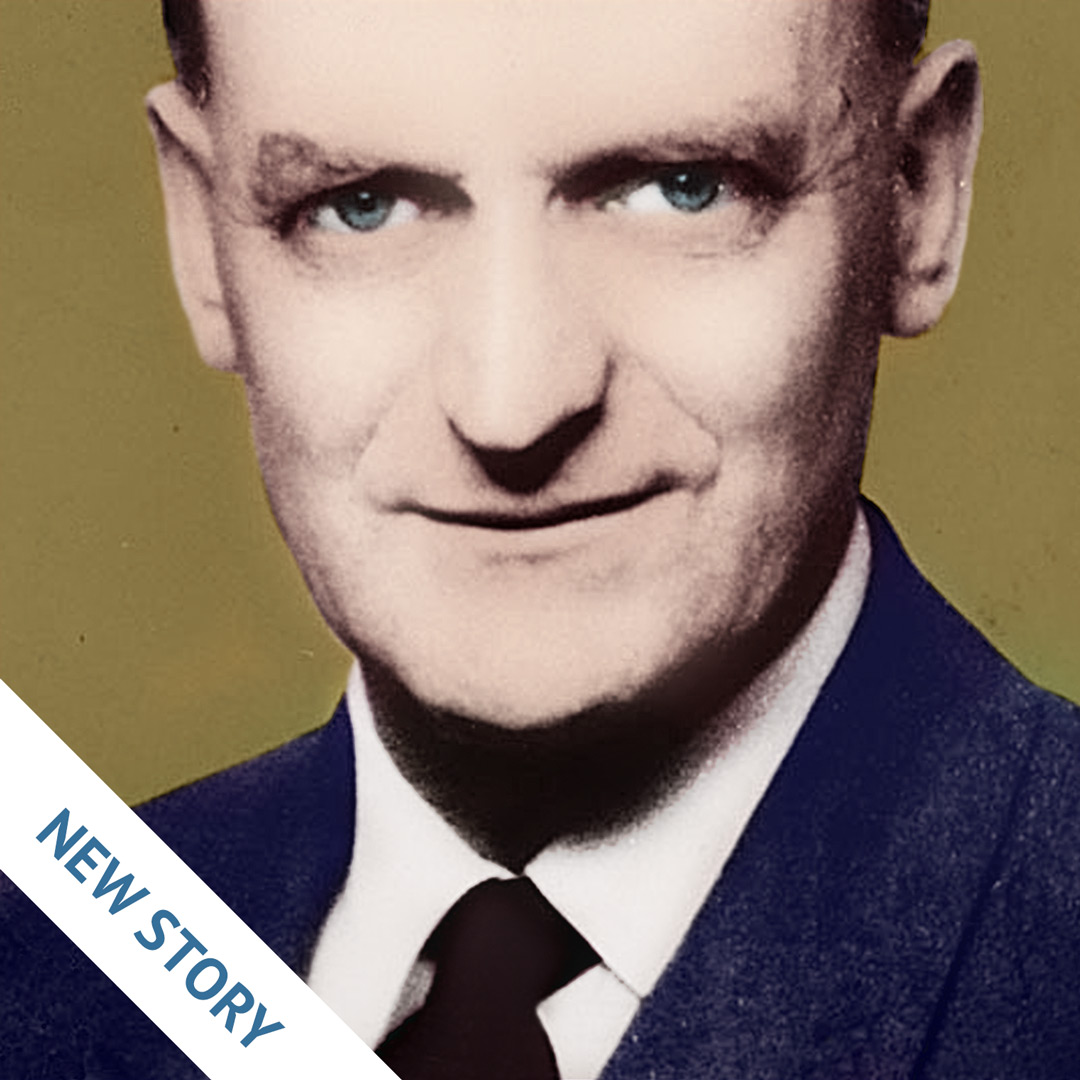

Peter Low – The New Zealand Herald

In any case the way to mitigate the harm of the Triads, in the same way as it is to mitigate that of the indigenous gangs, is to engage the communities that apparently harbour them and allow them to operate. Get people talking to each other across the divides and applying cultural and moral suasion on each other. The hype disappears, facts and realities emerge and the street feels and is a lot safer. The sad fact of the matter is that we can grid plot New Zealand communities and more or less predict a whole slew of sad realities for that particular area, low incomes, poor health, high crime. It is a world wide reality and a pattern borne out by other nations who have industrialised their criminal justice sector. Take the lead players in this regard, the USA. John Whitmire, Chairman of the Senate Criminal Justice Committee, was quoted in the New York Times late last year. He was commenting on Houston, Texas, where ten low-decile communities together account for only 15% of the City’s population, but account for half of the 6283 prisoners released in Houston in 2005. Parolees return to areas where support systems receive less money than in wealthier areas. Typically there are few resources, especially housing. Decades of ‘tough-on-crime’ legislation and low parole rates have multiplied the muster. Texas’ adult prison population has tripled since 1990. Senator Whitmire said:

“Certain lower socio-economic areas produce clients for the criminal justice system in a way that is analogous to the way that the welfare system created a cycle of first and second generation and third generation welfare recipients.”

And this is what we have in South Auckland and this is why our Asian countrymen and countrywomen feel compelled to march. Many of them call for harder harsher punishments for the young and brown. But the Cinia Ma abduction, the little 5 year old allegedly seized in an oriental tradition where business deals break down, suggests that people who live in even flash glasshouses shouldn’t throw stones. It is in the very deprived places, South Auckland, Manurewa, Porirua, Flaxmere, where families cower, and Asian business people are reputed to trade in trepidation, that we need to invest, socially, as well as economically rather than suppress and imprison. A Hong Kong investor, Jee M Sung Sung Family Trust, has just frustrated the plans of the Hastings District Council to undertake a community focused redevelopment of the now shoddy Flaxmere Shopping Centre by taking advantage of the recession and buying the whole shebang for $4.2 million. Mr Sungs’ two sons are based in Gisborne, another area that will be on the edge if the economy recedes further. What a boon to have Meng-Foon, a Maori-speaking Chinese, as Mayor of that very city. We need to partner up with whanau like these and work collaboratively for benefits all round. Post-settlement Maori and other New Zealanders are increasingly going to deal with Asia and Asians as China asserts itself as a lead player in the global economy. At the same time, if we are really serious about making our communities safer and stronger, we also have to rethink the destination and application of our ‘justice dollars”, the tougher penalties that Mr Low and others think will be the answer. This is not just my voice. Magnus Linklater, writing in the Times (May 28, 2008) says that we need to start pro-social effort

“…in hard cities where violence is hardwired into the landscape.”

Linklater cites Chicago, Brooklyn, Glasgow, Belfast, where

“…they all fight drugs, alcohol, gang culture and random violence; prison they all agree is failing to do the job.”

On the contrary using prison as a first resource

“…is the easiest and most useless of all options,”

as it simply breeds the next generation of criminals. Nobel Prize winning economist James Heckman calculated the comparative costs of early education and late imprisonment and concluded that it was 11 times more expensive to lock up a teenage criminal than it was to educate a young child away from a life of crime. This was pretty much the same theme presented by Baroness Vivien Stern (pictured) in her recent visit to New Zealand. In an address titled “Creating Criminals in a Market Society” she argued that New Zealand was not doing much at all about putting harm reduction before pointless punishment. She considers that New Zealand is in the business of creating criminals and using crime control as a way to manage people with problems whom society has failed to deal with. Baroness Stern suggests that we have redefined problems of social deprivation and poverty as problems of crime and of controlling risky and annoying behaviour.

as it simply breeds the next generation of criminals. Nobel Prize winning economist James Heckman calculated the comparative costs of early education and late imprisonment and concluded that it was 11 times more expensive to lock up a teenage criminal than it was to educate a young child away from a life of crime. This was pretty much the same theme presented by Baroness Vivien Stern (pictured) in her recent visit to New Zealand. In an address titled “Creating Criminals in a Market Society” she argued that New Zealand was not doing much at all about putting harm reduction before pointless punishment. She considers that New Zealand is in the business of creating criminals and using crime control as a way to manage people with problems whom society has failed to deal with. Baroness Stern suggests that we have redefined problems of social deprivation and poverty as problems of crime and of controlling risky and annoying behaviour.

During the winter solstice, with the moon turned on full beam, we planted out garlic and a few onions. I checked them yesterday and they are spouting proudly with rich green tendrils. I’d also put some Jersey Bennies alongside the corrugated iron walls of the chook house and placed some Maori spuds in amongst a ditch of corn stalks. The Bennies are up already—temperatures have been freakily high for this time of the year, 20 degrees last Sunday—but no sign of the Maori spuds just yet. The moon is right to plant again so we’ll put some more spuds in today. If we can get the frost cloth on fast enough we might have some early crops. Like the outcomes of our community action, ma te wa, we’ll wait and see.

Arohanui. D